Introduction

Sea stars of the family Benthopectinidae Verrill, 1899 inhabit mostly in deep-waters, within this family only the genera PontasterSladen, 1885 and CheirasterStuder, 1883 extend on to the shelf in shallow-waters (Clark & Downey, 1992). Benthopectinidae includes approximately 70 valid species distributed worldwide (Lambert, 2000; Mah & Blake, 2012).

The species of this family are characterized by having five very large pointed arms, longitudinally flexible dorso-ventrally and are characterized by having a single pair of muscle bands over the arms. The disc is small, the papular areas are restricted to the proximal region of each arm, and the marginal plates are alternating and overlapping (Downey, 1973; Clark & Downey, 1992; Benavides-Serrato, Borrero-Pérez, & Diaz-Sanchez, 2011). The taxonomy of the family has only been reviewed by Ludwig (1910) when describing it as the order Notomyotida. Later, Fisher (1911a) and Verrill (1915) made some additions and modifications on the taxonomy of the Pacific species. Since then, it was only A.M. Clark (1981) and A.M. Clark & Downey (1992) who reviewed the Atlantic species. The latter works are the most important in terms of genera and species taxonomy.

The biology and distribution of the Atlantic species of Benthopectinidae has been studied by some authors (Pain et al., 1982; Vázquez-Bader et al., 2008). There are also some taxonomic studies (Mortensen, 1927; Downey, 1973; Benavides et al., 2011) and checklists of species (Durán-González et al., 2005; Laguarda-Figueras et al., 2005; Alvarado & Solís-Marín, 2013). However, to date, there have been no taxonomic studies on the species found in the Mexican waters of the Gulf of Mexico. The aim of this work is to contribute to the study of deep-sea Benthopectinidae in this area and to update the external morphological characters with taxonomic value.

Materials and methods

Specimens from the five species of Benthopectinidae reported for the Mexican waters of the Gulf of Mexico deposited in the Echinoderm National Collection at the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico (ICML-UNAM) and the United States National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. (USNM), collected from 1952 to 2015, were taxonomically analyzed and measured using a digital caliper (TRUPER Caldi-6MP), the following measurements were taken in each specimen, if possible: major (R) and minor (r) radius in order to obtain the R/r ratio. For the taxonomic identity of the specimens, identification guides, original diagnosis and specialized literature were used (Perrier, 1881; Perrier, 1894; Sladen, 1889; Ludwig, 1910; Fisher, 1911a; Fisher, 1911b; Verrill, 1899; Verrill, 1915; Mortensen, 1927; H.L. Clark, 1941; Downey, 1973; A.M. Clark, 1981; Clark & Downey, 1992). Photographs of external taxonomical characters of each species were taken with a multifocal microscope Leica Z16 APOA at the Laboratorio de Microscopía y Fotografía de la Biodiversidad II (Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). A dichotomous identification key was elaborated, for which the main morphological characters used were: shape of the abactinal plates; location, shape, and number of marginal spines; shape and arrangement of papular areas; and the presence and number of spines and spinelets.

Results

A total of 566 specimens belonging to two genera (BenthopectenVerrill, 1884, CheirasterStuder, 1883), three subgenera (Barbadosaster A.M. Clark, 1981, Cheiraster, and Christopheraster A.M Clark, 1981) and five species (Benthopecten simplex simplex (Perrier, 1881) (seven specimens), Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus (Perrier, 1875) (78 specimens), Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planusVerrill, 1915 (165 specimens), Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei A.M. Clark, 1981 (186 specimens), and Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis (Perrier, 1881) (130 specimens)) were identified. Based on the material examined from both collections, the species with the highest number of records was C. (Cheiraster) planus, while B. simplex simplex and C. (Christopheraster) blakei were those with the least number of records.

Dichotomous key to the genera, subgenera, and species of the family Benthopectinidae of the Mexican waters of the Gulf of Mexico

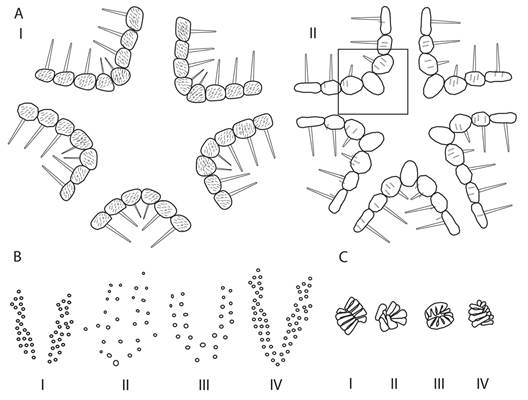

1. Regular interradial suture between the marginal plates, without odd interradial plates (Fig. 1A-I) (genus Cheiraster ). 2

1’. Interradial suture between marginal plates absent, one odd interradial plate in each series, the superomarginal inserted into the disc (Fig. 1A-II) (genus Benthopecten ). A single very large spine on the odd interradial plate, paired superomarginals, also with a single spine and a few spinelets; papular areas distally bifurcated (Fig. 1B-I) and the most distal pores aligned with the second or third superomarginal; adambulacral plates with five to seven furrow spines and two (on some plates one) subambulacral spines; oral plates with five or six furrow spines and three or four suborals; few and prominent numerous actinal pectinate pedicellariae (Fig. 1C-I). Benthopecten simplex simplex

2. Double papular areas, two lateral areas at each base of the arm proximally fused in large specimens (> 100 mm) forming a bilobed V-shaped area (Fig. 1B-IV), pores small and interstitial. Arrangement of the dorsal superomarginal plates framing the paxillary area in abactinal view. 3

2’. Papular areas start in a single large primary middle pore (Fig. 1B-II, 1B-III). 4

3. Parapaxiliform abactinal plates, not markedly convex, the most proximal crowded and highly variable in size, most of the larger plates ornamented with a central spine of more than 2 mm long surrounded by small spinules. Papular areas loosely joined and fused proximally only in large specimens, numerous pores, very small (subgenus Christopheraster ). Disc spines moderately long centrally, but not more than ½ of R, spaced and frequently extending to papular areas, gradually decrease in size until reaching that of a spinelet. Marginal spines similar in size. Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei

3’. Few relatively very large spines, rarely more than 15, restricted to the center of the disc, without gradually decreasing in size to that of a paxillary spinelet; the spine of the fourth superomarginal plate is conspicuously enlarged, mainly widened at base and fourth inferomarginal plate reduced and sometimes without any spine. Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis

4. Irregular papular areas, restricted to the arm base and distally bilobed (except in small specimens, < 50 mm), lobes may be unequal (Fig. 1B-II) (subgenus Barbadosaster ). Proximal abactinal plates polygonal in shape, stacked and not markedly convex, ornamented with numerous spinules forming two concentric rings around a central spinelet on the larger plates. Superomarginal plates wide, adambulacral plates with seven to nine furrow spines, two subambulacral spines, prominent pectinate pedicellariae (both types in 14 % of specimens) (Fig. 1C-III and Fig. 1C-IV), mainly in the actinal areas and less frequently between the inferomarginal plates. Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus

4’. Papular areas start in a primary middle pore and develop in a “U”-shaped double series (Fig. 1B-III). Abactinal plates parapaxiliform, the ones on the disc markedly convex and stacked together, on the disc and at the base of the arms ornamented with a central spinelet between small spinules. Adambulacral plates with a single subambulacral spine (subgenus Cheiraster ), abactinal plates rounded with a group of spinules forming a single ring around a central spine, superomarginal spines longer than the corresponding inferomarginal ones at least in the proximal half of the disc. Rounded adambulacral plates with a series of six to nine furrow spines, pectinate pedicellariae (Fig. 1C-II) present in some actinal plates and frequently in the inferomarginal plates. Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus

Fig. 1 A. Diagnostic morphological characters of species in the genera Cheiraster and Benthopecten: Cheiraster: subequal superomarginal plates (I). Benthopecten: presence of an odd interradial plate (II). B. Distribution of papular pores in Benthopecten simplex simplex (I), Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus (II), Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus (III), and Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei and Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis (IV). C. Types of pedicellariae in Benthopecten simplex simplex (I), Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus (II) and in Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei and Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis (III), Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus presents type III and may or not present type IV.

Systematics:

Family Benthopectinidae Verrill, 1899

Genus BenthopectenVerrill, 1884

Benthopecten simplex simplex (Perrier, 1881)

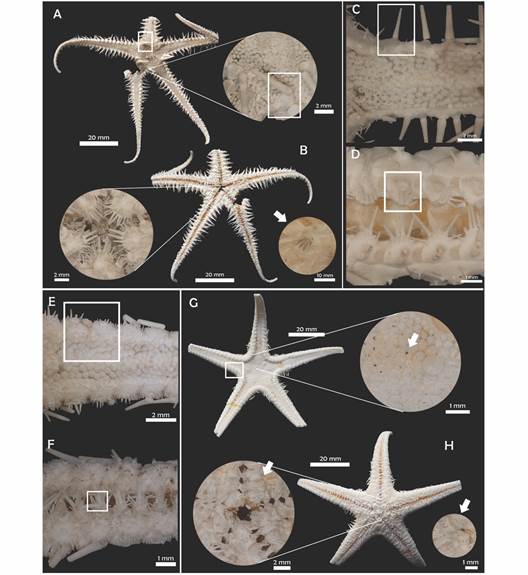

(Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B, Fig. 2C, Fig. 2D)

Archaster simplexPerrier, 1881: 28.

Pararchaster armatusSladen, 1889: 19, pls. 1, 4.

Pararchaster simplex.- Perrier, 1894: 253-256.

Benthopecten simplex.- Ludwig, 1910: 451, 464; Fisher, 1911a: 143; Verrill, 1915: 122; Downey, 1973: 40, pl. 12; Pain et al., 1982: 195.

Benthopecten armatus.- Farran, 1913: 2; Mortensen, 1927: 74, Fig. 41.

Benthopecten spinosus.- H.L. Clark, 1941: 26

Benthopecten chardyiSibuet, 1975: 238, 289, Fig. 3, pl. 1.

Benthopecten simplex simplex.- A.M. Clark, 1981: 130; A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992: 121, pl. 30.

Diagnosis (modified from A.M. Clark, 1981): R = 150 mm, R/r = 7.7-7.9. Multiple spinules in most of the proximal abactinal plates, two or three but sometimes 10 when they are accompanied by a spinelet or a bigger spine, especially in specimens with average R > 50 mm. Spines of the primary radial plates tend to be more developed than the ones on the primary interradial plates. Papular areas distally bifurcating, the distalmost pores level with the first three superomarginals or can extend to the fourth in bigger specimens. There is an odd interradial superomarginal plate (Fig. 2A) with a single very large spine, the other superomarginals also with a single spine and a few spinelets. Adambulacral plates with five to seven furrow spines and a single subambulacral spine (Fig. 2D). Oral plates with five or six furrow spines and three or four suboral spines. Pedicellariae highly modified, usually present in the actinal area, between the inferomarginals, and some abactinals (Fig. 2B).

Material examined: USNM E13210, one specimen, Tamaulipas (24°52’12” N & 94°19’47” W), 3 713 m; USNM E13219, five specimens, Veracruz (19°32’24” N & 95°4’11” W), 2 185 m; USNM E30697, one specimen, Baltimore (38°2’60” N & 73°27’0” W), 1 916 m.

Geographic and bathymetric distribution: Cape Cod; Gulf of Mexico, Tamaulipas, and Veracruz; Colombia and Guyana basins and from south and southwest of Iceland, Rockall Trough; Kattegat, Denmark; south of the Gulf of Guinea; 1 175 to 3 713 m (A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992; Durán-González et al., 2005).

Remarks: According to the original description (Perrier, 1881), the adambulacral plates usually have five to seven furrow spines, but in all the revised specimens there are five.

Fig. 2 A-D. Benthopecten simplex simplex (USNM E30697, E13219). A. Abactinal view and odd interradial plate with conspicuous spine, rectangle shows the spine. B. Actinal view and detail of oral plates; arrow shows pedicellariae. C. Detail of marginal spines, rectangle shows spine. D. Adambulacral spines, rectangle shows furrow spines and suboral spine insertion. E-H. Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus (USNM E23485, E12699). E. Detail of superomarginal plates, rectangle shows plate. F. Adambulacral spines, rectangle shows furrow and subambulacral spines. G. Abactinal view and detail of irregular shape of papular areas, rectangle shows superomarginal plates. H. Actinal view and detail of oral plates; arrow shows pedicellariae.

Genus CheirasterStuder, 1883

Subgenus Barbadosaster A.M. Clark, 1981

Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus

(Fig. 2E, Fig. 2F, Fig. 2G, Fig. 2H)

Archaster echinulatusPerrier, 1875: 348; Perrier, 1894: 263, pl. 10.

Cheiraster mirabilis.- Perrier, 1894: 276, pl. 20.

Cheiraster vincentiPerrier, 1894: 275.

Cheiraster echinulatus.- Perrier, 1894: 278; Verrill, 1915: 129; Downey, 1973: 42, pl. 13.

Pontaster oligoporusPerrier, 1894: 293.

Luidiaster vincenti.- Ludwig, 1910: 425.

Pectinaster echinulatus.- Ludwig, 1910: 449.

Pectinaster mixtusVerrill, 1915: 140, pl. 6, 15, 17; Downey, 1973: 43, pl. 14.

Pectinaster vincenti.- Verrill, 1915: 139.

Pectinaster oligoporus.- Verrill, 1915: 147.

Luidiaster mixtus.- H.L. Clark, 1941: 29.

Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus.- A.M. Clark, 1981: 112, Fig. 3A-F, Fig. 4A-H; A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992: 131, pl. 32B-E; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011: 143.

Diagnosis (modified from Downey, 1973): R = up to 70 mm, average R/r = 4.5-5.7. Little rigid and relatively short arms, abactinal plates polygonal and paxiliform, each one bears from eight to 25 granuliform spinelets and a small central spine. Each papular area has three to eight pores at the base of each arm without any arrangement (Fig. 2E), but in some big specimens the distal pores form two distal lobes. Superomarginal plates are very large and rectangular so that they invade the disc; as a result, the paxilar area on the arms is very narrow (Fig. 2G). Except for the first two interradial plates, the superomarginal plates have only one erect spine and they may have other small spinelets around. The inferomarginal plates have only one spine and about eight small spines. Adambulacral plates with seven to nine furrow spines which form a prolonged angle less than 90° (Fig. 2H). Two subambulacral spines, very prominent pedicellariae on the actinal plates (Fig. 2F), sometimes between the adambulacral plates.

Material examined: USNM E12581, one specimen, Quintana Roo (21°9’36” N & 86°25’48” W), 29 m; USNM E12778, one specimen, Campeche (23°0’0” N & 86°47’59” W), 482 m; USNM E12699, two specimens, Campeche (24°18’0” N & 87°49’47” W), 375 m; USNM E23485, one specimen, Bahamas (25°30’0” N & 79°20’59” W), 311 m; ICML-UNAM 8033, four specimens, Campeche (22°24’34” N & 91°34’86” W), 539 m; ICML-UNAM 8458, four specimens, Yucatán (24°16’60” N & 88°12’57” W), 455 m; ICML-UNAM 8468, five specimens, Quintana Roo (23°46’20” N & 87°06’64” W), 618 m; ICML-UNAM 8472, one specimen, Quintana Roo (23°48’38” N & 87°08’16” W), 613 m; ICML-UNAM 8680, three specimens, Campeche (22°15’87” N & 91°44’89” W), 250 m; ICML-UNAM 8725, two specimens, Yucatán (23°10’83” N & 89°59’71” W), 460 m; ICML-UNAM 8728, one specimen, Yucatán (23°14’95” N & 89°59’53” W), 536 m; ICML-UNAM 5068, 53 specimens, Quintana Roo (23°22’09” N & 88°06’09” W), 122 m.

Geographic and bathymetric distribution: Gulf of Mexico, Campeche, Yucatán, Quintana Roo; Florida strait, south to Nicaragua and Venezuela, east of Leeward Islands, Cuba, Curaçao, San Vicente, Colombia; 29 to 5 062 m (Clark & Downey, 1992; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011).

Remarks: The bathymetric range of this species is extended to its shallower limit, since it was previously reported from 130 to 5 062 m (Clark & Downey, 1992; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011), and in the present work it has been found at 29 m depth. There are two types of pectinate pedicellariae, the first ones are mounted on the surface of the actinal plates with a rounded margin, and the second ones are located between two actinal plates, half of the pedicellariae in one plate and the other half on the other, with irregular margins. These pedicellariae are not exclusive of the species, but it is important to note that both types may be observed in the same specimen, unlike the other four species that generally have only one type of pedicellariae. This was observed only in 14 % of the reviewed specimens.

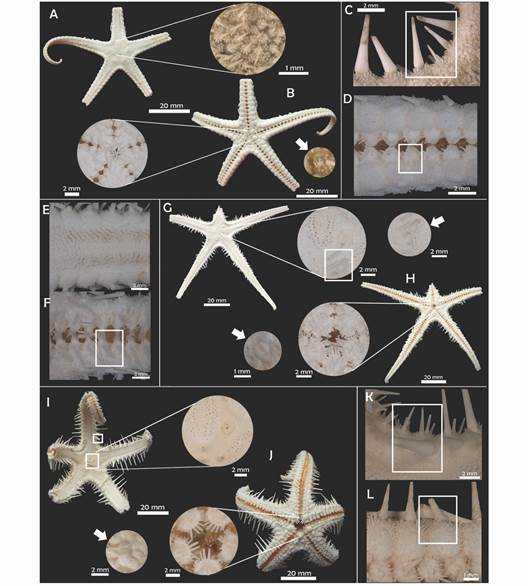

Fig. 3 A-D. Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus (USNM E41881, ICML-UNAM 11708). A. Abactinal view and detail of abactinal plates. B. Actinal view and detail of oral plates; arrow shows pedicellariae. C. Marginal spines, rectangle shows superomarginals longer than inferomarginales. D. Adambulacral spines, rectangle shows furrow spines and suboral spine insertion. E-H. Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei (USNM E23427, ICML-UNAM 8778). E. Detail of superomarginal plates, rectangle shows furrow spines and subambulacral spine. F. Adambulacral spines. G. Abactinal view, rectangle and arrow show the group of non-isolated spines that decrease in size towards the arms. H. Actinal view; detail of oral plates, arrow shows pedicellariae. I-L. Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis (USNM E23416). I. Abactinal view, rectangles show abactinal plates and isolated group of spines at the center of the disc, papular areas. J. Actinal view and detail of oral plates; arrow shows pedicellariae. K. Detail of superomarginals, rectangle shows the spine of the fourth superomarginal plate enlarged. L. Detail of adambulacral plates, rectangle shows the spine of the fourth inferomarginal plate reduced.

Subgenus CheirasterStuder, 1883

Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus Verrill, 1915

(Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B, Fig. 3C, Fig. 3D)

Cheiraster planusVerrill, 1915: 133, pl. 18.

Pectinaster gracilisVerrill, 1915: 145, pl. 6, 14, 15.

Cheiraster mirabilis. Downey, 1973: 41, pl. 13.

Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus.- A.M. Clark 1981: 116, Fig. 5A, Fig. 5B; A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992: 128, pl. 31A-C; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011: 140.

Diagnosis (modified from Verrill, 1915; Clark & Downey, 1992): R = up to 120 mm approximately, R/r = 6.1-8.9. Disc considerably broad and arms are very long and slender, abactinal plates are uniform in size, rounded and convex with a group of spinules. On the proximal plates the average number of spinules is 10, forming a ring surrounding a central spinelet (Fig. 3A). Papular areas start with one big single median pore and develop into two double U-shaped series, being irregular only in the biggest specimens. The plates of the papular areas next to the madreporite and in the central part of the disc are larger than the rest and have numerous spines. Marginal spines are well developed, conical and broad at the base. Superomarginal spines are distinctively larger than the corresponding inferomarginals (Fig. 3C), the rest of the plate is covered with fine spinelets and there is only one accessory spine. Adambulacral plates have six to nine rounded spines and one conical subambulacral spine mounted on a convex protuberance (Fig. 3D). Pectinate pedicellariae present on the actinal plates and on the inferomarginal plates (Fig. 3B).

Material examined: USNM E13215, seven specimens, Veracruz (21°30’0” N & 96°55’12” W), 1238 m; USNM E23587, six specimens, Quintana Roo (18°30’0” N & 87°36’35” W), 715 m; USNM E41881, 19 specimens, Louisiana, USA (27°23’60” N & 93°18’36” W), 732 m; ICML-UNAM 5024, one specimen, Quintana Roo (23°22’0” N & 88°06’0” W), 86.6 m; ICML-UNAM 5025, one specimen, Quintana Roo (22°23’02” N & 87°15’04” W) depth not recorded; ICML-UNAM 7980, four specimens, Veracruz (18°46’03” N & 94°25’96” W), 386 m; ICML-UNAM 7979, three specimens, Veracruz (18°47’0.43” N & 94°32’8.57” W), 380 m; ICML-UNAM 8029, four specimens, Campeche (22°24’15” N & 91°35’00” W), 548 m; ICML-UNAM 8033, seven specimens, Campeche (22°24’34” N & 91°34’86” W), 539 m; ICML-UNAM 8036, three specimens, Campeche (22°24’12” N & 91°35’75” W), 548 m; ICML-UNAM 9022, one specimen, Tamaulipas (24°55’58” N & 96°30’50” W), 700 m; ICML-UNAM 9026, 12 specimens, Tamaulipas (24°56’05” N & 96°29’18” W), 760 m; ICML-UNAM 9028, 24 specimens, Tamaulipas (24°56’48” N & 96°24’59” W), 821 m; ICML-UNAM 9193, nine specimens, Veracruz (18°57’107” N & 94°20’0” W), 671.9 m; ICML-UNAM 9196, six specimens, Veracruz (18°59’04” N & 94°19’09” W), 815 m; ICML-UNAM 9218, six specimens, Veracruz (19°06’33” N & 94°06’38” W), 867 m; ICML-UNAM 9222, one specimen, Veracruz (18°57’06” N & 94°06’61” W), 524 m; ICML-UNAM 9247, one specimen, Tabasco (19°08’81” N & 93°27’48” W), 677 m; ICML-UNAM 9260, one specimen, Tabasco (19°40’0” N & 92°45’13” W), 770 m; ICML-UNAM 8791, one specimen, Campeche (22°29’38” N & 90°43’66” W), 130 m; ICML-UNAM 9639, one specimen, Yucatán (23°36’02” N & 89°34’51” W), 435 m; ICML-UNAM 9707, one specimen, Quintana Roo (23°38’49”N & 87°04’84” W), 572 m; ICML-UNAM 9716, two specimens, Quintana Roo (23°40’58” N & 87°04’84” W), 642 m; ICML-UNAM 9746, eight specimens, Quintana Roo (23°26’70” N & 86°53’0” W), 633 m; ICML-UNAM 9826, two specimens, Campeche (22°20’18” N & 91°41’46” W), 428 m; ICML-UNAM 9850, one specimen, Campeche (22°26’00” N & 91°26’86” W), 546 m; ICML-UNAM 9900, two specimens, Tabasco (19°33’82” N & 93°01’46” W), 664 m; ICML-UNAM 11551, one specimen, Tamaulipas (24°55’0” N & 96°29’07” W), 766 m; ICML-UNAM 11555, three specimens, Tamaulipas (24°54’08” N & 96°31’40” W), 683 m; ICML-UNAM 11563, four specimens, Tamaulipas (24°55’0” N & 96°29’07” W), 765 m; ICML-UNAM 11617, one specimen, Veracruz (18°53’90” N & 94°08’37” W), 557 m; ICML-UNAM 11637, two specimens, Tabasco (19°08’99” N & 93°27’91” W), 690 m; ICML-UNAM 11644, five specimens, Tabasco (19°13’57” N & 93°54’88” W), 746 m; ICML-UNAM 11690, one specimen, Tabasco (19°04’61” N & 94°04’49” W), 828 m; ICML-UNAM 11700, one specimen, Tabasco (19°02’96” N & 94°05’33” W), 764 m; ICML-UNAM 11708, one specimen, Tabasco (18°54’99” N & 93°51’69” W), 419 m; ICML-UNAM 11741, two specimens, Tabasco (18°58’0” N & 94°07’57” W), 710 m; ICML-UNAM 12343, one specimen, Yucatán (23°22’45” N & 89°59’28” W), 582 m; ICML-UNAM 12386, four specimens, Yucatán (23°18’26” N & 89°56’60” W), 410 m; ICML-UNAM 12376, five specimens, Yucatán (23°13’76” N & 89°58’23” W), 392 m.

Geographic and bathymetric distribution: Gulf of Mexico, Tamaulipas, Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, Quintana Roo; Jamaica, Cuba, Honduras, Trinidad and Tobago, Nicaragua, Colombia, Las Antillas and Guyana; 86.6 to 1 339 m (Durán-González et al., 2005; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011).

Remarks: The bathymetric range of this species is extended to its shallower limit, since it was previously reported from 226 to 1 339 (Alvarado & Solís-Marín, 2013) and in the present work it has been found at 86.6 m depth.

Subgenus Christopheraster A.M. Clark, 1981

Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei

A.M. Clark, 1981

(Fig. 3E, Fig. 3F, Fig. 3G, Fig. 3H)

Cheiraster mirabilis.- Verrill, 1915: 124, pl. 14.

Cheiraster echinulatus.- Verrill, 1915: 131, pl. 14, 19.

Cheiraster coronatus.- H.L. Clark, 1941: 26.

Luidiaster enoplus.- H.L. Clark, 1941: 28.

Cheiraster enoplus.- Downey, 1973: 42, pl. 14.

Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei A.M. Clark, 1981: 113, figs. 1b, 2c-f; A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992: 132, pl. 32A, 33D, E; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011: 145.

Diagnosis (modified from A.M. Clark, 1981): R = up to 130 mm, R/r = 6.0-9.8/1 for large specimens, and 4.5-6.5/1 in specimens of R = 30-60 mm. Arms very long and become attenuated in larger specimens. Abactinal plates convex, polygonal, and very variable in size, the primary radial and interradial ones are conspicuous and have 25 small spinules, 10 on average; the larger plates develop a long spine and form a non-isolated group (Fig. 3E). Papular areas on each arm ill-defined, extensive, and distally bilobed with numerous pores that extend up to the third superomarginal plate. Superomarginal plates have only one spine (Fig. 3G), the larger ones are on the fifth and sixth plates; correspondent inferomarginal spines similar or slightly larger, with a small accessory spine below it. Actinal areas small and triangular in shape. Each adambulacral plate has seven to nine furrow spines, forming a 90° angle, but it can be obtuse (Fig. 3H). A single subambulacral spine and usually small spinules in the actinal view of the plate. Pectinate pedicellariae develop in the adradial actinal plates, on the adjacent margins of the adambulacral plates, and sometimes in the abactinal surface (Fig. 3F).

Material examined: USNM E23428, one specimen, Yucatán (21°16’48” N & 86°12’35” W), 412 m; USNM E23427, Bahamas (27° 48’36” N & 78°49’47” W), 824 m; USNM E23566, six specimens, Campeche (23°55’48” N & 87°31’48” W), 274 m; USNM E23509, four specimens, Campeche (23°58’12” N & 87°29’23” W), 366 m; USNM E23601, six specimens, Quintana Roo (18°30’0” N & 87°36’35” W), 715 m; USNM E38622, two specimens, Quintana Roo (18°49’48” N & 87°31’11” W), 695 m; USNM E23427, eight specimens, Bahamas (27°48’36” N & 78°49’47” W), 824 m; ICML-UNAM 8169, three specimens, Yucatán (22°24’7” N & 91°30’7” W), 407 m; ICML-UNAM 8778, one specimen, Yucatán (22°46’16” N & 90°46’88” W), 735 m; ICML-UNAM 12318, one specimen, Yucatán (23°33” N & 89°40” W), 358 m; ICML-UNAM 12385, 62 specimens, Yucatán (23°18’26” N & 89°56’60” W), 410 m; ICML-UNAM 12375, 92 specimens, Yucatán (23°13’ 74” N & 89°58’23” W), 392 m.

Geographic and bathymetric distribution: Gulf of Mexico, Campeche, Yucatán; Bahamas, southeast Florida, Cuba, Belize, Colombia, Honduras, Jamaica, north of Brazil; 250 to 1 030 m (being more abundant from 500 to 800 m) (Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011; Solís-Marín et al., 2014).

Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis

(Fig. 3I, Fig. 3J, Fig. 3K, Fig. 3L)

Archaster mirabilisPerrier, 1881: 27.

Cheiraster coronatus.- Perrier, 1894: 271; Ludwig, 1910: 455.

Cheiraster mirabilis.- Verrill, 1915: 124.

Cheiraster enoplusVerrill, 1915: 135, pl. 18.

Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis.- A.M. Clark, 1981: 112, Fig. 2A, Fig. 2B; A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992: 133; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011: 147.

Diagnosis (modified from Verrill, 1915): R = up to 185 mm, R/r = 7.5-8.8/1 for large specimens (R > 70 mm), R/r = 6-7.5/1 for R = 30-60 mm. Arms very long and thin. Center of the disc with a dozen long spines (Fig. 3I). Superomarginal plates somewhat small, imbricated and with a convex proximal edge, surface covered with numerous fine spinules. Papular pores form two symmetric lateral groups that extend up to the disc. Superomarginal plates have a marginal long, conical spine, the one of the fourth plate abruptly elongated (Fig. 3K), and the first three reduced. Inferomarginal plates covered with long but fine spinules, in the first three plates there are four to five spines that increase in size, the one in the fourth plate is reduced (Fig. 3L), the rest of the spines longer than the corresponding superomarginals; some of these plates have fasciculate rudimentary pedicellariae. Adambulacral plates with 10-12 furrow spines and one large, conical subambulacral spine (Fig. 3L). Prominent oral plates with about eleven spines, two or three pectinate pedicellariae between the interactinal plates (Fig. 3J).

Material examined: USNM E50647, one specimen, Quintana Roo (22°41’24” N & 86°40’48” W), 411 m; USNM E23416, three specimens, Bahamas (25°58’48” N & 78°12’0” W), 658 m; ICML-UNAM 8162, three specimens, Yucatán (22°28’08” N & 91°12’95” W), 416 m; ICML-UNAM 8714, one specimen, Yucatán (23°17’28” N & 89°56’73” W), 388 m; ICML-UNAM 9624, five specimens, Campeche (22°24’42” N & 91°30’35” W), 364 m; ICML-UNAM 9641, one specimen, Yucatán (23°30’98”N & 89°49’42” W), 422 m; ICML-UNAM 9661, four specimens, Yucatán (24°14’89” N & 88°12’59” W), 423 m; ICML-UNAM 9686, one specimen, Quintana Roo (24°21’45” N & 87°37’92” W), 812 m; ICML-UNAM 9691, one specimen, Quintana Roo (24°24’57” N & 87°38’22” W), 820 m; ICML-UNAM 9747, three specimens, Quintana Roo (23°26’70” N & 86°53’07” W), 633 m; ICML-UNAM 9769, one specimen, Quintana Roo, (23°35’46” N & 86°50’08” W), 806 m; ICML-UNAM 9825, 39 specimens, Campeche (22°20’18” N & 91°41’46” W), 428 m; ICML-UNAM 8759, one specimen, Campeche (22°46’23” N & 90°45’79” W), 728 m; ICML-UNAM 8773, three specimens, Campeche (22°33’ N & 90°48’ W), 346 m; ICML-UNAM 11690, one specimen, Tabasco (19°04’61” N & 94°04’49” W), 828 m; ICML-UNAM 9826, one specimen, Campeche (22°20’18” N & 91°41’46” W), 428 m; ICML-UNAM 12386, three specimens, Yucatán (23°18’26” N & 89°56’60” W), 410 m; ICML-UNAM 12376, nine specimens, Yucatán (23°13’76” N & 89°58’23” W), 392 m; ICML-UNAM 12385, 19 specimens, Yucatán (23°18’26” N & 89°56’60” W), 410 m; ICML-UNAM 12375, 30 specimens, Yucatán (23°13’74” N & 89°58’23” W), 392 m.

Geographic and bathymetric distribution: Gulf of Mexico, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatán, Quintana Roo; southeast Florida, Cuba, Jamaica; 342 to 1 470 m, being more abundant from 400 to 700 m depth (Clark & Downey, 1992; Durán-González et al., 2005; Benavides-Serrato et al., 2011).

Remarks: The bathymetric range of this species is extended to its shallower limit, since it was previously reported at 380 m (Alvarado & Solís-Marín, 2013), and in the present work it has been found at 342 m depth.

Discussion

The family Benthopectinidae corresponds to a group of organisms that occur mainly in deep waters and whose species richness consists of eight genera, and approximately 70 valid species (Mah & Blake, 2012). This family is the only one included in the order Notomyotida described by Ludwig (1910). Mah and Foltz (2011) suggested a phylogenetic hypothesis from Valvatacea and Paxillosida orders, in which the family Benthopectinidae was supported as a sister group to Pseudarchasteridae Sladen, 1889 and was included within the order Paxillosida. This was supported by Mah and Blake (2012) since they have shown close morphological resemblance to the Goniasteridae Forbes, 1841 family, as both families occur primarily in deep-sea or high-latitude and correspond to widely distributed taxa. Also, Linchangco et al. (2017) placed the order Paxillosida as sister to Cheiraster sp., showing results similar to those presented by Mah and Foltz (2011), since they did not use morphological characters either. However, in this study, the Benthopectinidae family was considered within the order Notomyotida, following the classification proposed by A.M. Clark & Downey (1992), until a phylogenetic reconstruction method is realized including morphological characters. So far, there have been no more detailed studies that are only focused on this taxon. The only previous taxonomic work was carried out by Clark (1981) for the Atlantic species where the author redefined the genera Cheiraster and PectinasterPerrier, 1885, reduced the genus LuidiasterStuder, 1883 to a subgenus of Cheiraster, described two more subgenera for Cheiraster, and three new species. The subdivision within the genera may be useful in some cases to identify certain morphological similarity between the species. However, the characters used for the designation of subgenera within the genera in this family cannot be applied in all cases, since the characters related to ontogeny such as the early or late development of certain spines, are highly variable, and therefore it is suggested that a complete family review that includes molecular methods and the use of morphological characters including ossicle morphology is realized to redefine the species and eliminate confusing or unnecessary subdivisions.

Five species of Benthopectinidae are reported for the Mexican waters of the Gulf of Mexico, which represents 6 % of the world diversity of this family. Since the species of this family are distributed in eight genera (Mah & Blake, 2012), the two found in these waters represent 25 % of the total genera of the family. Regarding the taxonomy of the species, Cheiraster (Christopheraster) mirabilis and Cheiraster (Christopheraster) blakei share morphological characteristics such as the shape of the papular areas of different ontogeny, this was described by Clark (1981) and showed drawings of the different arrangement that the species of the genus present, and that the development of the pores throughout the growth is very particular in these two species. The change in the pattern of pore distribution in both species is not very marked, but it can be appreciated in some of the reviewed specimens. Based on the review of the specimens from the Gulf of Mexico, we determined that, to differentiate both species, the two most important characters are: 1) the number and arrangement of spines on the disc, which are abundant and present in the entire disc, gradually decreasing in size towards the arms in C. (Christopheraster) blakei, and which are all similar in size and restricted to the center of the disc in C. (Christopheraster) mirabilis; and 2) the superomarginal spines, which are sub-equal in size in C. (Christopheraster) blakei, while in C. (Christopheraster) mirabilis the spine of the fourth superomarginal plate is much more developed than the rest. It is important to note that the last characteristic presents variation; while in the Bahamas specimens the spine of the fourth superomarginal plate is markedly larger than the rest (up to 15 mm as reported by A.M. Clark & Downey, 1992), in the Gulf of Mexico specimens, the spine is larger but not almost twice as large, as reported by Clark (1981).

In Cheiraster (Barbadosaster) echinulatus, one of the diagnostic characteristics of the species is the rectangular shape of the superomarginal plates that considerably invade the disc. The variation of shape of these plates is mainly that they tend to invade the disc, but, especially in small specimens, the plates are only slightly longer than they are wide, which means the rectangular shape is not as obvious as Perrier (1875) described. In the case of Cheiraster (Cheiraster) planus, the main characteristic is the marginal spines, since the ones in the superomarginal plates are larger in size than the corresponding inferomarginal ones. Although this species was described by Verrill (1915) from a single specimen, it is the most common species of the family in the Gulf of Mexico. Finally, Benthopecten simplex simplex, is a species whose type locality is the Gulf of Mexico, but a subspecies (Benthopecten simplex chardyiSibuet, 1975) has been reported in the Gulf of Guinea and Gabon (Clark & Downey, 1992). This subspecies is still considered valid, since it differs from B. simplex simplex by a delayed development of the disc spines and a late appearance of the second subambulacral spine, in addition to a greater number of adambulacral plates corresponding to the first 10 inferomarginal ones. According to Clark (1981), these can be considered a combination of extremes in the characters subject to variation in B. simplex simplex. In other words, they could simply be two highly variable characteristics. However, the subspecies has not been validated or refuted since there are no records in the rest of the Atlantic of an intermediate form or specimens that may suggest that these characters are simply subject to great variation.

A more detailed study may find that the diversity of the family is much greater and that there are many cryptic or overlooked species due to lack of definition between one species and another, as is the example of the synonym of B. simplex simplex: Benthopecten armatus (Sladen, 1889), synonymized with Benthopecten spinosusVerrill, 1884 by some authors, such as Grieg (1921) which is in fact a valid species, and treated as valid by other authors like Mortensen (1927) being finally synonymized with B. simplex simplex by Clark (1981). The present study represents the first updated compilation of the species of this family present in the Gulf of Mexico, as well as the first work providing external morphological characters of taxonomic importance to distinguish them. It is the first time that a dichotomous key for these species in the Mexican waters of the Gulf of Mexico is presented.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio