Introduction

In anurans, the male reproductive system is made up of the testes and a group of ducts that conduct spermatozoa to the outside (Oliveira et al., 2002). The testes are paired organs with an ovoid shape that are located in the abdominal cavity (Oliveira & Vicentini, 1998; Pierantoni et al., 2002). Internally they present two compartments, the germinal and the interstitial. In the first, they are organized by seminiferous tubules (Duellman & Trueb, 1994) where in turn there are cysts of spermatogonia, spermatocytes, spermatids, and spermatozoa morphofunctionally associated with Sertoli cells (Chavadej et al., 2000; Oliveira et al., 2002). For its part, the interstitium is the tissue between the seminiferous structures formed by collagen fibers, blood vessels, Leydig cells, and other connective tissue elements (Pudney, 1995; Yoshida, 2016). There are several findings related to the morphophysiology of the reproductive system in anurans. Among these, some have focused on aspects such as sperm cell morphology (Carezzano & Cabrera, 2010; Carezzano et al., 2013), the reproductive cycle (Ortiz & Díaz-Páez, 2001), plasma androgen level (Delgado et al., 1989), hormonal stimulants (Aguilar-Miguel et al., 2009), and their relationship with the development of secondary sexual characteristics (Rastogi et al., 1986; Kaptan & Murathanoğlu, 2008).

The morphology of spermatogenic cells is widely described within the order Anura and has been found to be similar (Delgado et al., 1989; Ko et al., 1998; Oliveira & Zieri, 2005). For the Neotropics, little has been studied about the processes of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis in this group of organisms (Carezzano et al., 2013). It has been evidenced that the majority of anurans present a testis with cystic cellular organization, although with differences in aspects such as pigmentation and thickness of the albuginea tunic (Carlos & Matta, 2009; Guillama et al., 2014). Dark pigmentation in the testes has been described in some species and is caused by cells called melanocytes that are randomly distributed in the albuginea tunic and the interstitium (Aoki et al., 1969; Oliveira et al., 2002; Guillama et al., 2014). These cells present association with some organs and structures mainly of the vascular system and the reproductive system, which generates intra-and inter-specific differences, for this reason, little is known to date about the function and role of these pigments at the gonadal level (Oliveira & Zieri, 2005; Franco-Belussi et al., 2009).

A unique aspect of the family Bufonidae is the presence of Bidder’s organ (BO) in the cranial part of the testis (Vitale-Calpe, 1969; Petrini & Zaccanti, 1998), whose existence has led to think of males as possible hermaphrodites (Ponse, 1927). This structure has been described in several species of neotropical distribution (King, 1908; Ponse, 1927; Alexander, 1932; Brown et al., 2002; Farias et al., 2002; Calisi, 2005). Historically this organ has been considered a rudimentary ovary (Petrini & Zaccanti, 1998) in which only previtellogénic oocytes are formed under natural conditions; on the contrary, laboratory experiments have shown that oocytes can reach mature vitellogénic stages (Pancak-Roessler & Norris, 1991; Tanimura & Iwasawa, 1992; Scaia et al., 2011). The BO has been reported in males and females of the same species with a similar histological morphology (Pancak-Roessler & Norris, 1991; Tanimura & Iwasawa, 1992; Duellman & Trueb, 1994; Farias et al., 2002); in the case of females, it is lost during the early phase of development while in males it remains throughout their life (King, 1908; Ponse, 1927; McDiarmid, 1971). Likewise, it is indicated that it is better developed in juveniles than in adults, where in some species it can degenerate during sexual maturity (McDiarmid, 1971). Although Bidder’s organ has been extensively studied, little is known about its functionality (Caroli, 1925; Brown et al., 2002; Silberschmidt-Freitas et al., 2015).

The genus Atelopus (Duméril & Bibron, 1841), toads, or harlequin frogs, include about 100 species distributed in moist lowland and highland forests, from Costa Rica to Bolivia (Frost, 2021). In Colombia there are about 45 spp, which are mostly endemic, being the country with the greatest number and diversity of this taxon (Frost, 2021). In Latin America, previous studies within the genus focus on distribution patterns (La Marca et al., 2005; Cusi et al., 2017), population dynamics (Tarvin et al., 2014), and aspects of its natural history such as ecology (Lötters, 1996), reproductive biology (Lynch, 1986), territoriality (Crump, 1988), and emerging diseases (Lampo et al., 2017). In addition, some works on phylogenetic relationships and biogeography have included this genus (Lötters, 1996; Pramuk et al., 2008; Lötters et al., 2011). In Colombia, the issues addressed in the genus Atelopus have focused on ecological aspects such as foraging behavior (Rueda-Solano & Warkentin, 2016), substrate use (Granda-Rodríguez & Del Portillo-Mozo, 2007), thermal ecology (Rueda-Solano et al., 2016a), coloration type (Rueda-Solano, 2008; Rueda-Solano, 2012), tadpole morphology (Rueda-Solano et al., 2015; Pérez-González et al., 2020), monitoring (Gómez-Hoyos et al., 2014), and diseases caused by the chytrid fungus (Rueda-Solano et al., 2016b; Flechas et al., 2017). Several authors have studied important aspects of reproductive biology associated mainly with the breeding season, reproductive effort, and the interspecific amplexus (Pérez-González et al., 2017; Rocha-Usuga et al., 2017). However, other issues such as gonadal morphology (McDiarmid, 1971; Siqueira et al., 2013), sexual maturity (La Marca et al., 1989), and mating patterns (Barrantes-Cartín, 1986; Crump, 1988; Lötters, 1996; Karraker et al., 2006) are still unknown to most representatives of the genus. This group of harlequin frogs is one of the most endangered in the world (La Marca et al., 2005), whose populations have decreased in high mountain habitats, including areas with little intervention (Pounds & Crump, 1994; Pounds et al., 2006). Turning the five endemic frog species that inhabit the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta (SNMS) into objectives of great interest for the conservation of the genus (IUCN, 2021), among which are the three species under study.

This investigation describes for the first time the testicular morphology in adult males of Atelopus laetissimus Ruiz-Carranza et al., 1994, Atelopus nahumae Ruiz-Carranza et al., 1994, and Atelopus carrikeri Ruthven, 1916 to know part of their reproductive cycle, providing information on the histological and structural characteristics of the spermatogenic cells. Additionally, possible intersexuality is suggested by the presence of Bidder’s organ in the cranial part of the testis. It is necessary to highlight that currently, these species are at threat of extinction that is why knowing part of its reproductive biology will contribute to its conservation.

Materials and methods

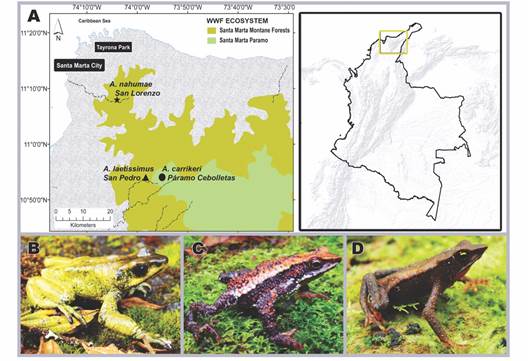

Study area: Three sites were sampled at different altitudes in the SNSM in the department of Magdalena in Northern Colombia (Fig. 1A).

Initially the locality of A. carrikeri which corresponds to the Páramo de Cebolletas (3 500 m.a.s.l) located on the Sevilla River to the West of the SNSM (10°54’03” N & 73°55’05” W) and to the East in the San Pedro de la Sierra district in Ciénaga-Magdalena (Fig. 1A, Fig. 1B). The popuation of A. laetissimus, located in the Pascual stream (2 100 - 2 200 m.a.s.l.), San Pedro de la Sierra, SNSM (10°54’3.70” N & 73°55’4.50” W) (Fig. 1A, Fig. 1C). Finally, the A. nahumae specimens that occur at the headwaters of the Gaira river (1 560 m.a.s.l.), Serranía de San Lorenzo, SNSM (11°10’2.0” N & 74°10’41.5” W) (Fig. 1A, Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1 Geographical location of the sampled localities in the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta- Magdalena, Northern Colombia, and images of the study species. A. Altitudinal distribution of the localities: San lorenzo-location of Atelopus nahumae, San Pedro-location of Atelopus laetissimus and Páramo Cebolletas-location of Atelopus carrikeri. B. Atelopus carrikeri. C. Atelopus laetissimus. D. Atelopus nahumae.

Field sampling and specimen data: Five field studies were carried out during June-July 2017 and 2018 according to the reproductive season of the species (Carvajalino-Fernández et al., 2008; Granda-Rodríguez et al., 2008; Rocha-Usuga et al., 2017), locating adult males by body size, vocalizations, and the presence of nuptial pad (Sinsch, 1988; Duellman & Trueb, 1994; Carezzano et al., 2013). To find the organisms, the active search method and the recording by visual encounter were applied (Crump & Scott, 1994), with an exploration time that ranged from 6 pm to 11 pm for 3 days in the San Lorenzo sector and 4 days in the Cebolletas sector. The capture was carried out manually with the permission of the Corporación Autónoma Regional del Magdalena, resolution No 0425 of 2015. The 15 adult males collected (Atelopus laetissimus N = 5; Atelopus nahumae N = 5, and Atelopus carrikeri N = 5) were transported to the laboratory in plastic containers with little water to avoid desiccation (Carezzano et al., 2013). The sacrifice of the organisms occurred by anesthesia, through abdominal rubbing with Garhocaine gel (based on 20 % Benzocaine) (Phuge & Gramapurohit, 2013). Subsequently, an incision was made in the abdominal wall to remove the gonads for anatomical and morphological analysis. It is worth mentioning that each specimen was treated as established by the Ethics Committee for the correct handling of organisms, approval CICUAL No C.FUA. 17_006 of 2017, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá-Colombia. The supporting vouchers were deposited at the Universidad del Magdalena in Santa Marta-Colombia with catalogue number CBUMAG: ANF:01019 - CBUMAG: ANF:01023, CBUMAG: ANF:01028, CBUMAG: ANF:01036.

Histological analysis: Testes were removed and fixed in Bouin’s solution for 48 h at room temperature (Phuge & Gramapurohit, 2013); subsequently preserving them in 70 % ethyl alcohol. After this period, they were washed in distilled water to remove the excess Boiun. They were then dehydrated in the gradual series of ethanols (70 %, 80 %, 90 %, 96 %) for 4 hours at each step and two final steps in 100 % ethanol, a 4-hour change, and a 12-hour change (Hopwood, 1990; Pikle et al., 2017). Rinsing was carried out in two steps by xylol also at 4 h and 12 h (Guillama et al., 2014). The infiltration-inclusion was performed in Paraplast plus (Mc Cormick ®) for 12 h at 55 °C (Asenjo at al., 2011) and from this, cross-sections were obtained with LEICA RM 2125 ® rotary microtome, of 3 μm-thick. The sections were stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin (Luna, 1968) and Mallory-Heidenhain-Azan-Gomori’s (Gomori, 1939; Clark, 1973). The sections obtained were examined with a Nikon 80i eclipse® and Nikon eclipse Ni photonic microscope equipped with a differential interference contrast (DIC) system. Also, some sections were analyzed with fluorescence, using the DAPI-FITC-Texas triple band excitation filter which incorporates an excitation filter with narrow band pass windows in the violet (395 to 410 nm), blue (490 to 505 nm), and green (560 to 580 nm) spectral regions. The images were digitized with a Nikon DS-Fi1® camera using the NIS-Elements software version 4.30.02. In the course of the study, it was found that the processes of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis occurred similarly in the three Atelopus species analyzed, therefore, for the detailed description of the germ cells the species that provided the best illustrations were chosen.

Results

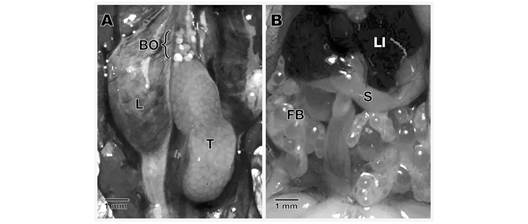

The testes are located in the abdominal cavity, ventral to the kidneys joined to them by a membrane, the gonadal mesenterium or mesorchium. In general, they are oval-shaped, compact, light yellow organs, and with little vascularization (Fig. 2A). Fatty bodies are found in their cranial extremity, with several thin extensions of color yellowish and slightly translucent (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2 Anatomical aspect of the testis and Bidder’s organ in Atelopus laetissimus. A. Location of the testicle and Bidder’s organ. B. Association with other organs present in the abdominal cavity. BO: bidder’s organ; FB: fatty bodies; L: lung; LI: liver; S: stomach; T: Testicle.

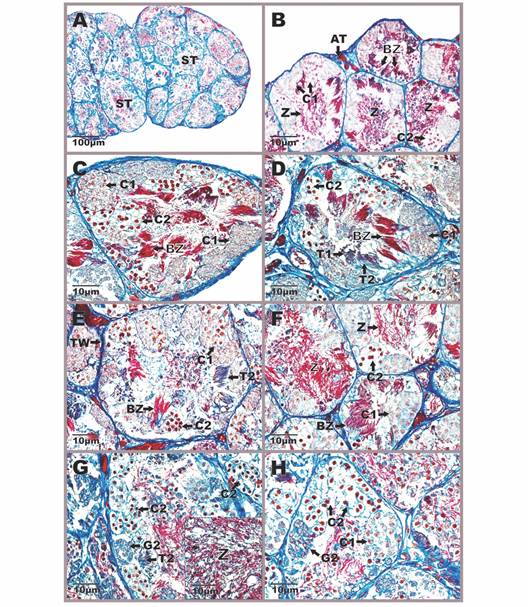

Histologically, the testes are lined by the albuginea tunic, a thin layer of regular dense connective tissue in which collagen fibers and blood vessels predominate. The tunic is thin and has no pigment cells. Inside this layer, numerous seminiferous tubules of hexagonal contour are distinguished in which germ cell cysts can be observed at different times of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). In cysts, cells unite in the same state of differentiation, indicating that they have synchrony of development (Fig. 3A, Fig 4A). Surrounding the seminiferous tubules is the interstitial tissue consisting of loose connective tissue formed by Leydig cells (testosterone-producing) and loose blood capillaries (Fig. 3B). Leydig cells have a rounded or oval-contour nucleus and the chromatin is slightly condensed; at the same time, they can be seen separately or in groups near the blood vessels (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3 Aspect of the testicular anatomy in Atelopus carrikeri during the breeding season A. General view of the male gonad with abundant seminiferous tubules B. Detail of the interstitial tissue between two seminiferous tubules showing Leydig cells and blood capillaries. Figures A and B stained with Hemtaoxilin-eosin (photon microscopy with the differential interference contrast-DIC system). C. Primary spermatogonia, in the field with a DAPI-FITC-Texas triple band excitation filter. One per cyst is seen near the wall of the seminiferous tubule. D-H. Seminiferous tubules with spermatogenic cell cysts at different stages of development. Mallory-Heidenhain-Azan-Gomori’s stain (photon microscopy with the differential interference contrast-DIC system). AT: albuginea tunic; BV: blood vessels; BZ: bundle of spermatozoas; C1: primary spermatocytes; C2: secondary spermatocytes; G1: primary spermatogonia; G2: secondary spermatogonia; IT: interstitial tissue; L: leydig cells; ST: seminiferous tubule; T1: early spermatids; T2: late spermatids; TW: tubular wall; Z: spermatozoa in the lumen.

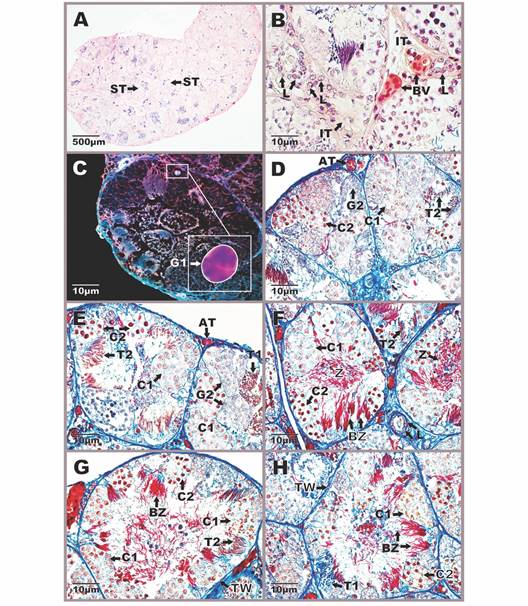

Germ cells were identified according to morphology, degrees of nuclear material condensation, and cystic arrangement (Fig. 3C, Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E, Fig. 3F, Fig. 3G, Fig. 3H, Fig. 4A, Fig. 4B, Fig. 4C, Fig. 4D, Fig. 4E, Fig. 4F, Fig. 4G, Fig. 4H). Spermatogonia are the cells that initiate the spermatogenic process and undergo multiple mitotic divisions that give rise to a large clonal population of germ cells. Of these, two types were identified: primary spermatogonia (I) and secondary spermatogonia (II). The former are the largest cells with a rounded contour, large polymorphic nucleus, and mostly euchromatic (Fig. 3C). They are usually very close to the seminiferous tubule wall and are arranged one per cyst (Fig. 3C). From their mitotic division, secondary spermatogonia originate, cells that do form cysts and are smaller than the primary. Regarding their morphocytological characteristics, they present the basophilic cytoplasm, small spherical nuclei, and scarcely heterochromatic (Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E, Fig. 4G, Fig. 4H).

Fig. 4 Aspect of the testicular anatomy in Atelopus nahumae during the breeding season. A. General view of the male gonad with abundant seminiferous tubules. B-H. Seminiferous tubules with spermatogenic cell cysts at different stages of development. Photomicrographs stained with Mallory-Heidenhain-Azan-Gomori’s (photon microscopy with the differential interference contrast-DIC system). AT: albuginea tunic; BZ: bundle of spermatozoas; C1: primary spermatocytes; C2: secondary spermatocytes; G2: secondary spermatogonia; ST: seminiferous tubule; T1: early spermatids; T2: late spermatids; TW: tubular wall; Z: spermatozoa in the lumen.

In relation to the next stage of development, two classes of spermatocytes were identified: primary spermatocytes (I) and secondary spermatocytes (II). Primary spermatocytes originate from the mitotic differentiation of secondary spermatogonia and constitute the most abundant phase during the spermatogenesis process. These are cells with oval contour, large euchromatic nucleus, without nucleolus, and abundant cytoplasm (Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E, Fig. 3F, Fig. 3G, Fig. 3H, Fig. 4B, Fig. 4C, Fig. 4D, Fig. 4E, Fig. 4F, Fig. 4H). Generally, they are observed in different phases of the first meiotic division, presenting various degrees of condensation in the chromatin. These cells differ from spermatogonia II because they are larger and the cysts are larger. For their part, secondary spermatocytes are haploid cells that are distinguished by being smaller than their predecessors (spermatocytes I). They have basophilic nuclei, with a rounded contour, condensed chromatin, and the cytoplasm is translucent without any granulations (Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E, Fig. 3F, Fig. 3G, Fig. 3H, Fig. 4B, Fig. 4C, Fig. 4D, Fig. 4E, Fig. 4F, Fig. 4G, Fig. 4H).

Continuing with the development phases, spermatids are the result of the second meiotic division and their cell population has a wide variety of shapes ranging from spherical to elongated (Fig. 3E, Fig. 4D). In the analyzed species were found in two stages: early spermatids (I) and late spermatids (II). Early spermatids have a round shape, spherical nucleus, slightly compressed, and condensed chromatin (Fig. 3E, Fig. 3H, Fig. 4D). These differ from spermatocytes II because they are smaller and with denser chromatin. Late spermatids are elongated cells with an elongated nucleus and condensed chromatin (Fig. 3D, Fig. 3E, Fig. 3F, Fig. 3G, Fig. 4D, Fig. 4E, Fig. 4G). In some preparations, they are seen to have weakly stained flagella (Fig. 3E, Fig. 4D). Spermatids undergo the spermiogenesis process to give rise to spermatozoa, which are the most elongated and basophilic cells of the germ lineage; their characteristics include a compact nucleus and reduced cytoplasm. These were observed at two moments of spermiogenesis, in the first phase, they form compact groups like fascicles due to their association with Sertoli cells, in such that the proximal part that contains the nucleus is associated with these nourishing cells and the distal part that corresponds mainly to the flagellum is located towards the lumen of the cyst (Fig. 3F, Fig. 3G, Fig. 3H, Fig. 4B, Fig. 4C, Fig. 4D, Fig. 4E, Fig. 4F). In the second stage, they completely lose the fascicular arrangement and are free towards the lumen of the seminiferous tubules (Fig. 3F, Fig. 4B, Fig. 4F, Fig. 4G).

Additionally, the specimens of the three analyzed species presented a Bidder’s organ in the cranial part of the testis (Fig. 5A, Fig. 5B).

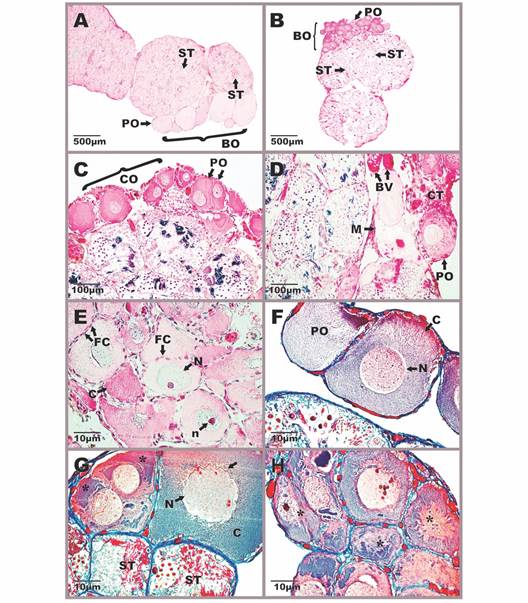

Fig. 5 Morphophysiology of Bidder’s organ in Atelopus carrikeri and Atelopus nahumae. A-B. Location of the Bidder’s organ in the cranial portion of the testis. C. Cortex region with previtellogénic oocytes. D. Region of the medulla formed by connective tissue and blood capillaries. E-F. Different-sized previtellogénic oocytes surrounded by a simple flat epithelium. G-H. Atretic oocytes with nuclear and cytoplasmic disintegration (*). Sections stained with Mallory-Heidenhain-Azan-Gomori’s and Hematoxylin-eosin staining (photon microscopy with the differential interference contrast-DIC system). Photomicrographs A, F-H of A. carrikeri individuals and images B-E of A. nahumae specimens. BO: bidder’s organ; BV: blood vessels; C: cytoplasm; CO: cortex; CT: connective tissue; FC: follicular cells; M: medulla; N: nucleus; n: nucleolus; PO: previtellogénic oocytes; ST: seminiferous tubule. The scalloped nuclear envelope of atretic oocytes (↓).

This organ in vivo appears yellow and slightly translucent (data not illustrated). Histologically, it is made up of two regions: the cortex and the medulla (Fig. 5C, Fig. 5D). The medulla is the intermediate tissue that nourishes the oocytes, which constitutes a loose irregular connective tissue with numerous blood capillaries (Fig. 5D). In the cortex, there are abundant previthellogenic oocytes of different sizes, surrounded by a layer of follicular cells (Fig. 5C). Follicular cells form a simple flat epithelium (Fig. 5E). For their part, oocytes are large cells, with an acidophilic nucleus and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 5C, Fig. 5D, Fig. 5G, Fig. 5H). There were also abundant atretic oocytes with nuclear and cytoplasmic disintegration (Fig. 5G, Fig. 5H). The nuclear membrane of oocytes in the atresia process appears undulating and the nucleus loses its oval shape (Fig. 5G, Fig. 5H). In general, the absence of some type of specialized tissue that separates the Bidder’s organ from the testicular region is appreciated, beyond the connective tissue that nourishes them. Therefore, bidderian oocytes are close to the seminiferous tubules with cysts in different spermatogenic stages.

Discussion

The testicular architecture of A. laetissimus, A. nahumae, and A. carrikeri presented great similarity with the descriptions of other species of the same family such as Rhinella arenarum (Cavicchia & Moviglia, 1983), Anaxyrus woodhousii (Atherton, 1974), and Bufo bufo (Falconi et al., 2004). Germline cells exhibited intense spermatogenic activity and cyst arrangement, being a common appearance in anurans and a predictive property of anamniotic testicular evolution (Atherton, 1974; Lofts, 1974). Cysts form a hematotesticular barrier that provides an optimal microenvironment for germ cell maturity and is a diagnostic feature of the Anura order (Cavicchia & Moviglia, 1983). In general, all stages of spermatogenesis were identified, although there was a predominance of spermatids (early and late) and spermatozoa (in fascicles and free), which confirmed sexual maturity and reproductive activity of the organisms (Iturriaga et al., 2012; Pacheco-Florez & Ramírez-Pinilla, 2014). This suggests that the analyzed species may present continuous spermatogenic activity (Burgos & Mancini, 1948; Oliveira et al., 2002), as occurs in most species of neotropical distribution where all cell stages are present throughout the year (Rastogi, 1976; Lofts, 1987; Oliveira et al., 2002). However, to corroborate this hypothesis, it would be necessary to carry out samplings in non-reproductive seasons.

The morphocytological characteristics of the primary spermatogonia analyzed in this work are similar to those reported in the literature for various groups of anurans (King, 1907; Cavicchia & Moviglia, 1983; Oliveira & Vicentini, 1998). In contrast, for some species like Peltophryne fustiger, Pelophylax ridibunda, and Dendropsophus minutus primary spermatocytes constitute the largest cells (Kaptan & Murathanoğlu, 2008; Sanz-Ochotorena et al., 2008; Ferreira & Mehanna, 2012). In relation, to the next stage of development that includes secondary spermatogonia, a phase of intense cell division that remains until the formation of early spermatids (Lofts, 1974; Rastogi et al., 1988) it was possible to verify great similarity with the descriptions of other species including Pseudis limellum (Ferreira et al., 2008). These are generally more basophilic cells than primary spermatogonia (Jamieson, 2003), which contrasts with what was observed in R. arenarum (Burgos & Fawcett, 1956; Cavicchia & Moviglia, 1983) and D. minutus (De Souza-Santos & De Oliveira, 2008). At the same time, secondary spermatogonia were one of the scarcest cell types in the sections analyzed and even in the testes of some species it has not been found (Asenjo et al., 2011; Iturriaga et al., 2012).

In this research, it was observed that primary spermatocytes were commonly larger than secondary spermatogonia, which is due to the growth phase they experience during prophase I (Salas & Martino, 2008). In this period, chromatin presents a variation in the degree of condensation, being a common aspect with our observations and in the descriptions of other anurans (Ortiz & Díaz-Páez, 2001; Villagra et al., 2014). Additionally, they were distinguished in greater numbers than secondary spermatocytes as reported in other taxonomic groups (Ferreira et al., 2008). On the other hand, the secondary spermatocytes were observed smaller and with denser chromatin than their congeners, the primary spermatocytes. These cytological characteristics are similar to some representatives of the family Bufonidae (Echeverría & Maggese, 1987) and other species like Calyptocephalella gayi (Hermosilla et al., 1983) and Ceratophrys cultripes (Báo et al., 1991).

In this work, two stages are described for spermatids in a manner consistent with what some authors have found (Ortiz & Díaz-Páez, 2001; Oliveira et al., 2002). Initially, they were rounded cells that lengthened as they matured, once in the late spermatid phase, they no longer form cysts but are organized into fascicles as observed in this study (Lofts, 1974; Oliveira et al., 2002). However, in other taxa such as P. ridibunda three stages of development have been described, which includes an intermediate phase (Kaptan & Murathanoğlu, 2008). The morphological and histological characteristics of the spermatozoa and their arrangement in the seminiferous tubules did not vary in relation to that described in other works (Taboga & Dolder, 1991; Scheltinga et al., 2002). In this investigation, the Sertoli cells could not be observed, perhaps due to the lack of detail in the sections or of more histological sections, a fact that contrasts with most studies where they have been described morphofunctionally associated with spermatogenic cells (Carezzano et al., 2013). Nevertheless, late spermatid bundles were observed in the analyzed preparations, which indicates the presence of these nourishing cells.

The albuginea tunic did not present pigment cells in a common way with most anurans (Duellman & Trueb, 1986; Franco-Belussi et al., 2009). However, the presence of pigments has been recorded in several species including some of the genus Atelopus like A. varius, A. longirostris, and A. senex (McDiarmid, 1971; Franco-Belussi et al., 2009; Guillama et al., 2014). Sanz-Ochotorena et al. (2011) describe pigments in the testes of four Cuban anurans and attribute them a protective function against anthropogenic contamination and solar radiation. Additionally, McDiarmid (1971) suggests that they could be associated with the reproductive condition or with protection from ultraviolet light. On the other hand, it is considered that the melanin present in testicular melanocytes can protect male gametes from oxidative stress (Galván et al., 2011). However, this type of hypothesis would need more studies, given the testes are located in the abdominal cavity protected by other tissues, which would not imply the need to develop pigments to protect themselves from some cytotoxic effect caused by ultraviolet radiation. Other findings in anurans relate these pigments to an extracutaneous pigmentation system that is present in several organs in addition to the primary sexual characteristics, where the mode of appearance and the number of melanocytes is highly variable among species (Oliveira & Zieri, 2005). Accordingly, Franco-Belussi et al. (2009) studied the testes of seventeen species of the Leptodactylidae, finding that the distribution of melanocytes was variable, and therefore there were differences in the degree of pigmentation of the gonads, proposing that it could be an intrinsic characteristic of the species or physiological response. Therefore, the role of these testicular pigments is still unknown, and more exhaustive investigations are required taking into account ecological, histological, and phylogenetic aspects in the genus Atelopus.

The presence of the Bidder’s organ is registered for the first time in the analyzed species, which has been reported in other species of the genus Atelopus (Griffiths, 1954; Griffiths, 1959; McDiarmid, 1971). Likewise, it is present in most lineages of the family Bufonidae (Ponse & Guyénot, 1927; Alexander, 1932; Brown et al., 2002; Falconi et al., 2007) excluding Melanophryniscus (Echeverría, 1997; Peloso et al., 2012) and Truebella (Graybeal & Cannatella, 1995). Although certain authors consider the Bidder’s organ a synapomorphy of the clades derived from bufonids, the findings in the species A. laetissimus, A. nahumae, and A. carrikeri are contradictory since the genus Atelopus constitutes an early divergent lineage of bufonids (Pramuk et al., 2008). So, it is a character shared only by part of the family (Frost et al., 2006). Atelopus is a monophyletic group (Lötters et al., 2011), related to other genera of the family in which BO has been described, such as Osornophryne, Peltophryne, Bufo, and Rhinella (Graybeal & Cannatella, 1995; Pramuk, 2006; Pyron & Wiens, 2011; Pereyra et al., 2021). Therefore, the anatomical, morphological, and histological characteristics seen in BO are similar to those recorded in other investigations where the presence of this structure has been detected (Griffiths, 1954; Griffiths, 1959; Silberschmidt-Freitas et al., 2015; Copa, 2019). Our findings indicate that the BO does not reach the formation of viable oocytes and, on the contrary, they enter atresia and are reabsorbed, which is similar to that registered in Bufo bufo, Rhinella icterica, Rhinella marina, and Peltophryne empusa (Zaccanti & Gardenghi, 1968; Farias et al., 2002; Abramyan et al., 2010; Copa, 2019). However, some authors described the presence of vitellogénic oocytes in the BO of some bufonids as R. marina and R. arenarum during the breeding season (McCoy et al., 2008; Scaia et al., 2011). Additionally, Lambert et al. (2019) reported that some adult males of the Rana clamitans changed sex and another group of organisms presented oocytes in their testes (inter-sex) in pristine conditions, despite this, the factors that can cause this sexual reversal is unknown.

In the Bidder’s organ, abundant degenerated and atretic oocytes were identified similarly with other bufonids, such as R. marina and R. arenarum (Brown et al., 2002; Scaia et al., 2011). This could be due to the lack of stimuli to continue its development or to the absence of a specialized tissue that separates the BO from the testicles (Silberschmidt-Freitas et al., 2015). The latter would be explained by the hormonal regulation of some androgens that can cause oocyte degeneration and at the same time inhibit the uptake of estradiol for vitellogenesis to occurs (Calisi, 2005). Despite this, different studies consensus that oogenesis is not completed in males under natural conditions (Silberschmidt-Freitas et al., 2015). Our findings on the presence of the Bidder’s organ in the three Atelopus species studied, allow us to suggest that males may possibly present sexual reversion because this organ could be used in the case of a population decrease in females as a possible strategy reproductive. Considering that this taxonomic group is highly threatened, further research in this direction could contribute to understanding the stability of their populations and their current conservation status. Additionally, research on the morphohistology of the testis is important to have a broader understanding of the reproductive biology of the genus Atelopus and of neotropical anurans in general, for which literature is scarce.

Ethical statement: authors declare that they all agree with this publication and made significant contributions; that there is no conflict of interest of any kind; and that we followed all pertinent ethical and legal procedures and requirements. All financial sources are fully and clearly stated in the acknowledgements section. A signed document has been filed in the journal archives.

uBio

uBio