Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Share

Revista de Biología Tropical

On-line version ISSN 0034-7744Print version ISSN 0034-7744

Rev. biol. trop vol.55 n.1 San José Mar. 2007

Bird diversity and conservation of Alto Balsas (Southwestern Puebla), Mexico

Jorge E. Ramírez-Albores

Museo de Zoología, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza, UNAM, México DF, México. Postal address: Manuel Bonilla # 357, Manzana 44, Col. Santa Martha Acatitla, Delegación Iztapalapa. C.P. 09510, México, DF, México; jorgeramirez22@hotmail.com

Received 13-III-2002. Corrected 22-II-2006. Accepted 13-X-2006.

Abstract: Knowledge of the composition of the bird community in Alto Balsas (southwestern Puebla, Central Mexico) is needed for management programs aiming at protection and conservation of bird species and their habitats I studied sites with tropical deciduous forest. Data were obtained during 1666 hours of field work in 238 days from March 1998 to September 2000. Six permanent transect (3.5 km long and 100 m wide; 30 to 40 ha in each transect) were used to determine species richness in the study sites. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index was calculated for each site and Sorensens index was used to assess similarity between sites. One-way analysis of variance was used to test for differences between sites in species richness and diversity values. A total of 128 species were recorded, Tepexco (n = 75, H´= 3.76) and Puente Márquez (n = 61, H´= 3.62) were the sites that showed the greatest specific richness and diversity. However, species richness and diversity seasonally patterns were similar among sites (ANOVA p > 0.05), with highest diversity during the rainy season. Most species were resident; 42 were migrants. The avifauna was represented by 30 species associated with tropical deciduous forest and 12 from open habitats or heavily altered habitats. Insectivores were the best represented trophic category, followed by carnivores and omnivores. Rev. Biol. Trop. 55 (1): 287-300. Epub 2007 March. 31.

Key words: avian diversity, richness, tropical deciduous forest, Alto Balsas, Mexico.

Dramatic reduction and fragmentation of forest cover in several parts of the world have prompted many to ask what the impacts of such changes are on animal abundance, species richness and community dynamics (Faaborg et al. 1995, McGarigal and McComb 1995). Forest fragmentation in the Neotropical region has been considered an important force in the loss of biodiversity (Bierregaard and Lovejoy 1989). Decreases in the number of bird species and changing avifaunal composition have been documented by many works (Bierregaard 1990, Aleixo and Vielliard 1995). The regulation of diversity and abundance in animal communities has intrigued ecologist for many years, but their study has evoked as much controversy as consensus (MacArthur and Wilson 1967). Many studies have assumed that the community is in equilibrium, and many of them sought to support some favored ecological process rather than weighing sev eral to determine their relative importance (Wilson and Comet 1996). Monitoring tempo ral changes of avifauna can provide valuable information on factors influencing popula tion dynamics, interactions, community struc- ture, and conservation (Ornelas et al. 1993). Seasonal changes in abundance and number of species have been studied in several temper ate avian communities (Anderson et al. 1981, Best 1981), but rarely in tropical regions (Karr 1981, Blake 1992, Blake and Loiselle 2000).

The Alto Balsas region is located in central Mexico (Tlaxcala, Puebla, Morelos and Guerrero states), south of the mountainous Trans-volcanic belt. It runs west to east over a vast portion of relatively flat terrain, and occurs mostly below 1000 m (except on isolated peaks; Guizar and Sánchez 1991, WWF 2001). The Balsas River and its drainage basin delineate the regions eastern boundary, while the mountains of Sierra Madre del Sur mark the western boundary along the Pacific coast. The Balsas basin has been also termed the "Balsas Depression" (because it forms a valley descending down to 200 m) in the west. The northern side of the depression is a plateau (containing the highest elevations) that reaches 1000 m above sea level, with few, scattered peaks at 2000 m (WWF 2001). In terms of the fauna, the Balsas dry forest is considered as a zone with high fauna diversity (e.g., mammalian, papilionid butterflies, birds and herpetofauna; Challenger 1998, Escalante et al. 1998).

Several ornithological studies have been carried out at Alto Balsas region: Martin del Campo (1937), Sutton and Burleigh (1942), Davis and Rusell (1957), Rojas (1995), Navarro (1998), Feria (1997, 2001, 2002), Ramírez-Albores (2000), Argote-Cortés (2002), Ramírez-Albores and Ramírez (2002), Abundis (2003) and Almazán (2003). The purpose of this study was to describe avian diversity, examined the variation in species richness and diversity values in the tropical deciduous forest in sites of Alto Balsas (southwestern Puebla) in Central Mexico. These forests contain a large numbers of wild birds that are ecologically specialized, locally endemic, and extremely sensitive to habitat loss. Deforestation, pollution, extensive agriculture, and introduction of sheep and bovine cattle are seriously threatening these forests, and many bird species.

Materials and methods

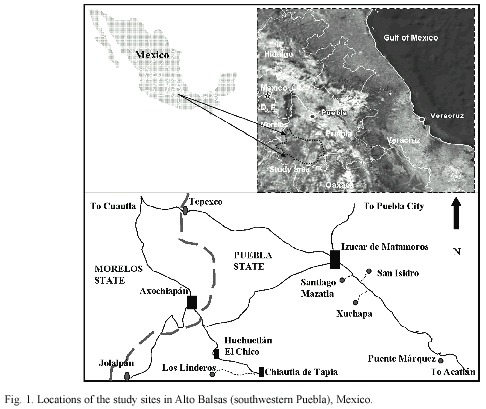

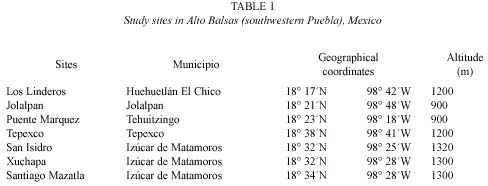

Study site: The study was conducted in sites of Alto Balsas in the southwestern Puebla (18°39´N, 98°58´W) in Central Mexico (Fig. 1, Table 1). Altitudinal range is from 800 to 1500 m a. s. l. (Table 1). The climate is tropical subhumid, with a dry season (that can last up to eight months) in which most or all trees lose their leaves and mean annual temperature is 23 °C. The precipitation levels are always below 1200 mm/year (INEGI 1987, Guizar and Sánchez 1991). The study area is characterized by the tropical deciduous forest associated with secondary forest, riparian vegetation (gallery forest), cattle pastures, agricultural fields and suburban zones. Some species common to tropical deciduous forest are Bursera morelensis, B. fagaroides, B. grandifolia, Ficus sp., Lysiloma sp., Ipomomoea sp., Pseudobombax palmeri, Ceiba parvifolia, Prosopis laevigata, Mimosa luisana and Erythryna sp. (Rzedowski 1978, INEGI 1987). Arid tropical scrub is also common element of this community, principally giant columnar cacti (Pachycereus weberi, P. dumortieri, Neobuxbaumia tetetzo and Stenocereus stellatus). The herbaceous stratum is poorly developed, but species such as Bouteloua curtipendula, B. rothrockii and Hilaria semplei can be found. The isolation of the Balsas dry forests from other forests of its kind has promoted the diversification of many taxa, resulting in a high number of endemic species. For this reason, this is one of the most studied and most appreciated regions in terms of its value for biological conservation (Escalante et al. 1998).

Data birds: Bird surveys were conducted between March 1998 and September 2000. I used a transect method (Emlen 1971) to conduct monthly censuses in each site: San Isidro, Jolalpan, Los Linderos, Santiago Mazatla, Santa María Xuchapa, Puente Marquez and Tepexco (Table 1). A total of 35 transect (five permanent transect for each site; 3.5 km long) were used to determine species richness in the study sites. I recorded each bird seen or heard within the survey area during each survey. A complete daily census along a transect consisted of five surveys: three in the morning (0700-1100) and two in the evening (1600-1900). Each transect was surveyed where the tropical deciduous forest was associated with others types of vegetation (secondary forest, cattle pastures, arid tropical scrub, agricultural fields and riparian vegetation) by determining differences on species composition between them. Scientific nomenclature order follows American Ornithologists Union check-list (1998).

Seasonal variation was determined following criteria: winter visitor (non-breeding visitor present during the northern winter), summer resident (breeds in the region, but is present only for a period during the northern summer), transient (non-breeding visitors only present during spring and/or autumn migration), resident (breeds and resides within its range throughout the year) and occurrence (non-breeding, includes vagrant and winter records; Howell and Webb 1995). Relative abundance (sense, Stiles 1983, Arizmendi et al. 1990, Ramírez-Albores and Ramírez 2002): abundant (total of 40 or more individuals recorded daily), common (17 to 39 individuals recorded daily), scarce (11 to 16 individuals recorded), irregular (five to ten individuals recorded) and rare (one to four individuals recorded). Preferred habitats for each species was determined in function of the vegetation community where the specie were conducting some activity (e.g., reproduction, breed), in agreement a Stiles (1983): tropical deciduous forest, riparian vegetation, secondary forest, arid tropical scrub, aquatic (large streams, rivers, ponds, lakes, lagoons), aerial (flying above terrestrial or aquatic habitats), open habitats or heavily altered habitats (agricultural fields, suburban zones, cattle pastures).

The feeding category assigned to each species was determined according to the food most often eaten and literature data: insectivores, frugivores, nectarivores, carnivores, granivores, omnivores, granivore-insectivores (mixed diet with a higher proportion of seed), insectivore-frugivores (mixed diet with a higher proportion of insects), granivore-insectivore-frugivores (mixed diet), carnivore-insectivore-frugivores (mixed diet) and carnivore-insectivores(mixed diet with a higher proportion of small vertebrates).

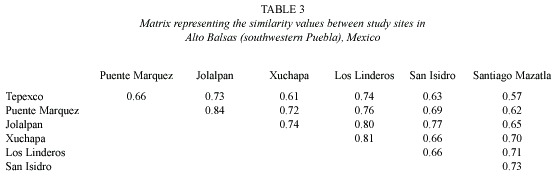

Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H = -∑ pi ln pi) was calculated for each site (Magurran 1988). Similarity between sites, using the Sorensens index of similarity [IS =2j / (a + b)] where j is the number of species common to both sites, a is the number of species in site A, and b is the number of species in site B. It ranges from 0-1 with increasing similarity of the two sites (Magurran 1988). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for differences between sites in species richness and diversity values.

Results

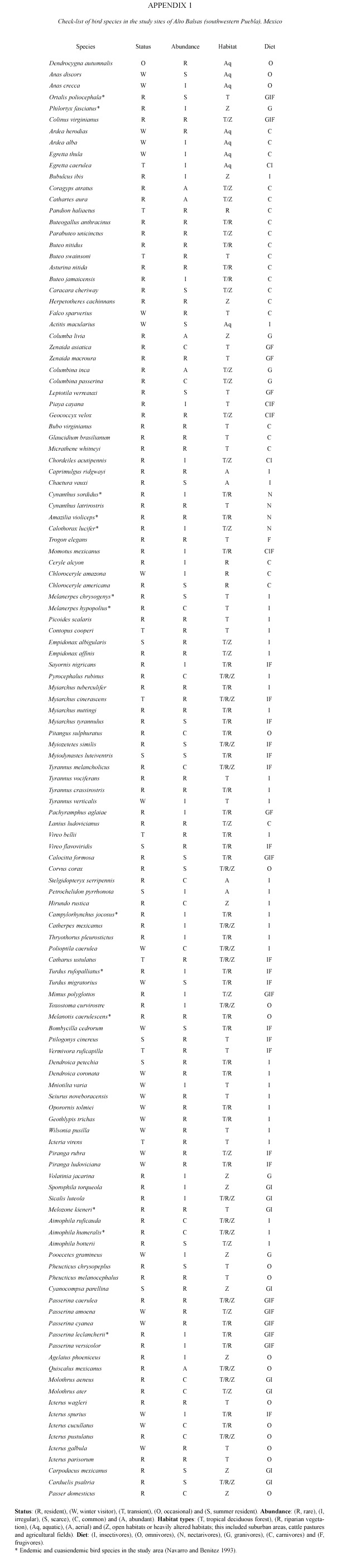

A total of 128 species grouped into 34 families were recorded at the area during 1666 hours of field work during 238 days (Appendix 1). The Tyrannidae family shows the highest species richness in the study sites (17 species), followed by Icteridae (10 species) and Parulidae (8 species) (Appendix 1).

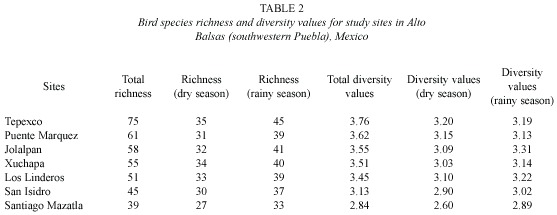

Overall species richness varied from 39 to 75, while overall diversity values ranged from 2.84 to 3.76 (Table 2). The fewest diversity were found in Santiago Mazatla (H´= 2.60) and the most in Tepexco (H´= 3.20) in the dry season. In the rainy season, the fewest diversity were found in Santiago Mazatla (H´= 2.89) and the most in Tepexco (H´= 3.19) and Jolalpan (H´= 3.31). However, species richness and the diversity values for the sites were seasonally similar (ANOVA, p>0.05); with highest diversity during the rainy season (Table 2). The similarity of species composition between sites indicates that there was a tendency for similar habitats to present similar species composition (Table 3). The highest similarity indexes were for Puente Marquez-Jolalpan (0.84) and the smallest similarity was for Tepexco-Santiago Mazatla (0.57).

Of the species recorded in this study, 86 species were residents, and the remaining of the species were migrants (Appendix 1). Relative abundance of species recorded during this study was 54 rares, 33 irregulars, 19 scarces, 16 commons and six abundants (Appendix 1).

In the habitat selection, 30 species were recorded in the tropical deciduous forest, 12 in open habitats or heavily altered habitats, eight aquatics, four in riparian vegetation and four aerial, of this group of species, only were recorded in these habitats (Appendix 1). The remaining species were detected in two or more habitats. Insectivores were representing by the greatest number of species, followed by carnivores and omnivores (Appendix 1). Granivores and nectarivores were representing by few species in all sites. Many birds occur in the rainy season (July-October), when insects and fruits are most abundant.

Discussion

The 128 bird species recorded in this study represent about 26% of the species in Puebla (Rojas 1995, reported 481 species to Puebla) and 12% of the birds of Mexico (Arizmendi and Marquez-Valdelamar 2000). This study has shown that study sites in Alto Balsas supports a high diversity of birds. Factors that contribute to determining avian diversity and abundance can be sorted into two levels, which are not entirely independent (Brown and Maurer 1987). Furthermore, the area is influenced for two biotic provinces: Trans-volcanic belt and Balsas Depression that presents a topographic complexity, and this to help to capacity of movements of the birds (Escalante et al. 1998).

The avifauna in the area is a species-rich as other similar tropical deciduous forest areas in Mexico (Chamela-Cuixmala in Jalisco; Arizmendi et al. 1990, Ornelas et al. 1993), owing to that many species are associated with the tropical deciduous forest corridor and have continuous distributions from northern Sonora, Mexico to Central America (Arizmendi et al. 1990, Ornelas et al. 1993). Twenty-nine species encountered in this study had not been recorded previously for the study region (Rojas 1995, Feria 1997, Ramírez-Albores 2000). Of these, three were new recorded for Puebla: Dendrocygna autumnalis, Egretta thula and Parabuteo unincinctus (Rojas 1995).

Seasonal changes in richness and total number of species may be due to resident species joining during the dry season only, the absence of summer visitors during the dry season, and seasonal variation in frequency with which some species associated (Maldonado-Coelho and Marini 2004). I expected higher bird diversity in more diverse sites but my results contradict this expectation. The winter distributions of most western North American Neotropical migratory land bird species are centered in western Mexico. Several studies have demonstrating that many birds carry out seasonal movements relationships with the rainy seasons, probably in function of the availability variation of food resources (Powell 1989, Levey and Stiles 1992, Ornelas et al. 1993), habitat structure and climatic conditions (Malizia 2001).

Habitats occupied by many migrants in winter, the density and proportion of migrants in most habitats, the diversity of migrants and residents that co-occur in flocks, the extent of participation in flocks by local avifauna and the proportion of migratory species that participates are all unique ornithological features of western Mexico (Hutto 1984). Behavioral some migratory of the birds is owing to that follow the phenology of resources that they use (Ornelas and Arizmendi 1995). This pattern permitted the birds proposed the dependency different types of resources requires: capacity to colonize new habitats, mobility to the able to follow changes in resource abundance, knowledge of the changes in resource in the landscape and the spatial distribution of these resources (Ornelas and Arizmendi 1995).

Tropical forest avifauna typically are characterized by the presence of many rare species (Karr et al. 1990, Terborgh et al. 1990, Loiselle and Blake 1992) that will be affects to food resources, structure and complexity of habitat or to the spatial and temporal availability of resources, indicated that communities are very inequality. However, the number of abundant species is very low, but these species have a high ecological success, and determining the conditions of the entailed species a theirs; established a sui generis feature of the communities, this is that include few abundant species and many rare species (Krebs 1978). Species locally abundant on average tended to be more widespread than locally rare species. This is also a consistent trend among birds (Gaston 1996). However this apparent correlation may be influenced by the higher overall detectability of common species.

The result of this study illustrate the continuing need for inventory efforts focused on Mexican birds and I considered this area is very important for bird conservation, because yet exits a great richness and abundance of endemic bird species to the region: Ortalis poliocephala, Philortyx fasciatus, Cynanthus sordidus, Amazilia violiceps, Calothorax lucifer, Melanerpes chrysogenys, M. hypopolius, Empidonax affinis, Campylorhynchus jocosus, Turdus rufopalliatus, Melanotis caerulescens, Melozone kienerii, Aimophila humeralis and Passerina leclancherii (Navarro and Benitez 1993, Escalante et al. 1998).

Rapid deforestation in the neotropics has undoubtedly had an impact on birds. The recent increase of second growth forest, cattle pastures and agriculture fields has resulted in an increase in the abundance of species dependent upon these habitats. Conservation efforts often are focused on regions or sites that support threatened, endemic, or rare species. Thus, knowledge of the distribution patterns of threatened species can be an important argument for protection of different areas (Wege and Long 1995).

This study showed that there is no marked difference in bird species diversity between dry and rainy seasons in the study sites in Alto Balsas. The pattern of distribution could also be due to local patchiness caused by the fragmentation of historically contiguous habitat due to agricultural development in the sites. Knowledge of the composition of the bird communities of the region and the specific or temporary uses which the different species make of the region allowed provide elements witch can be included or modified in a management program, and in this was the protection and conservation of the species and their habitat will be a success.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Museo de Zoología (Facultad de Estudios Superiores Zaragoza, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México). I sincerely thank Alfredo Bueno for comments and suggestions during the field work. I thank Guadalupe Ramírez, Eduardo Tepale, Ayerím Lopez and Alejandro Abundis for their assistance in data collection.

Resumen

Este estudio describe la diversidad avifaunística en sitios del Alto Balsas (suroeste de Puebla) en el Centro de México y examina la variación en la diversidad de las especies de aves. El estudio fue llevado a cabo en sitios con presencia de bosque tropical caducifolio. Los datos fueron obtenidos durante 1666 horas de trabajo de campo en 238 días de Marzo 1998 a Septiembre 2000. Se realizaron seis transectos permanentes (de 3.5 km de longitud y 100 m de ancho; de 30 a 40 ha en cada transecto) para determinar la riqueza de especies en los sitios de estudio. Se calculó el índice de diversidad de Shannon-Wiener para cada sitio y el índice de Sorensen fue usado para calcular la similitud en la composición de especies entre sitios. Un análisis de varianza de una vía fue usado para comprobar si existían diferencias entre los valores de riqueza y diversidad de especies de cada sitio. Un total de 128 especies de aves fueron registradas, Tepexco (n = 75, H´= 3.76) y Puente Márquez (n = 61, H´= 3.62) fueron los sitios que mostraron los valores de riqueza y diversidad de especies más altos. Sin embargo, la riqueza de especies y los valores de diversidad (p > 0.05) en los sitios fueron estacionalmente similares, con una mayor riqueza y diversidad durante la época de lluvias. La mayoría de las especies registradas fueron residentes y 42 fueron migratorias. La avifauna fue representada por 30 especies asociadas al bosque tropical caducifolio y 12 fueron asociadas a hábitats abiertos o altamente alterados. Los insectívoros fueron el gremio alimenticio mejor representado, seguido por los carnívoros y omnívoros. El conocimiento de información de la comunidad avifaunística de esta región nos permite proporcionar elementos que puedan ser incluidos en programas de manejo, protección y conservación de las especies de aves y sus hábitats.

Palabras clave: diversidad de aves, riqueza, bosque tropical caducifolio, Alto Balsas, México.

References

Abundis S., A. 2003. Evaluación del valor de conservación de áreas similares en la región del Alto Balsas, con base en un estudio ornitológico. Tesis de Licenciatura, UNAM, México DF. 56 p. [ Links ]

Aleixo, A. & M.E. Vielliard. 1995. Composição e dinãmica da avifauna da mata de Santa Genebra, Campinas, São Paulo, Brasil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 12: 493-511. [ Links ]

Almazán N., R.C. 2003. Patrones de riqueza de las aves de la subcuenca del río San Juan, Guerrero. Tesis de Licenciatura, Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, Guerrero, México. 75 p. [ Links ]

American Ornithologists´ Union. 1998. Check-list of North American birds. Allen, Washington, D.C., USA. 55 p. [ Links ]

Anderson, B.W., R.D. Ohmart & J. Rice. 1981. Seasonal changes in detection of individual bird species, In Ralph, C. J. & J. M. Scott (eds.). Estimating the numbers of terrestrial birds. Stud. Avian Biol. 6: 262-264. [ Links ]

Argote C., A., A. Bueno, J.E. Ramírez-Albores, J.E. Pérez, M.G. Ramírez, M. Martínez, T.P. Feria & F. Urbina. 1999. AICA: C-40 "Sierra de Huautla". In H. Benítez, M.C. Arizmendi & L. Márquez (eds.). Base de Datos de las Áreas de Importancia para la Conservación de las Aves (AICAS). Cipamex-Conabio-FMCN-CCA. México DF. [ Links ]

Argote C., A. 2002. Distribución de la avifauna del bosque tropical caducifolio de la Sierra de Huautla, Morelos, México. Tesis de Maestría, UNAM, México DF. 93 p. [ Links ]

Arizmendi, M.C., H. Berlanga, L. Márquez-Valdelamar, L. Navarijo & J.F. Ornelas. 1990. Avifauna de la región de Chamela, Jalisco. Cuadernos del Instituto de Biología No. 4, UNAM, México, DF. 62 p. [ Links ]

Arizmendi, M.C. & L. Márquez-Valdelamar. 2000. Áreas de importancia para la Conservación de las Aves en México. Cipamex, México, DF. 470 p. [ Links ]

Best, L.B. 1981. Seasonal changes in detection of individual bird species, In Ralph, C. J. & J. M. Scott (eds.). Estimating the numbers of terrestrial birds. Stud. Avian Biol. 6: 252-261. [ Links ]

Bierregaard, R.O., Jr. 1990. Avian communities in the understory of the Amazonian forest fragments, p. 33- 343. In A. Keast (ed.). Biogeography and ecology of forest bird communities SPB Academic. The Hague, Netherlands. [ Links ]

Bierregaard, Jr., R.O. & T.E. Lovejoy. 1989. Effects of forest fragmentation on Amazonian understory bird communities. Acta Amazonica 19: 215-241. [ Links ]

Blake, J.G.1992. Temporal variation in point counts of birds in a lowland wet forest in Costa Rica. Condor 94: 265-275. [ Links ]

Blake, JG. & B. A. Loiselle. 2000. Diversity of birds along an elevational gradient in the Cordillera Central, Costa Rica. Auk 117: 663-686. [ Links ]

Brown, J. H. & B. A. Maurer. 1987. Evolution of species assemblages: effects of energetic constraints and species dynamics on the diversification of North America avifauna. Am. Nat. 130: 1-7. [ Links ]

Challenger, A. 1998. Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México, pasado, presente y futuro. Conabio-Instituto de Biología, UNAM-Agrupación Sierra Madre, México, DF. 847 p. [ Links ]

Davis, W. B. & R. J. Russel. 1953. Aves y mamíferos del estado de Morelos. Rev. Soc. Mex. Hist. Nat. XIV: 77-121. [ Links ]

Emlen, J. T. 1971. Population densities of birds derived from transect counts. Auk 88: 323-342. [ Links ]

Escalante, P., A. G. Navarro & A. T. Peterson. 1998. Un análisis geográfico, ecológico e histórico de la diversidad de aves terrestres de México, p. 279-304. In T. P. Ramamorthy, R. Bye, A. Lot & J. Fa (eds.). Diversidad biológica de México. UNAM, México, DF. [ Links ]

Faaborg, J., M. Brittingham, T. Donovan & J. Blake. 1995. Habitat fragmentation in the temperate zone, p. 357- 380. In T.E. Marin & D.M. Finch (eds.). Ecology and management of neotropical migratory birds. Oxford University, Oxford, England. [ Links ]

Feria A., T.P. 1997. Diversidad y distribución avifaunística en una localidad del municipio de Chiautla de Tapia, Puebla. Tesis de Licenciatura, UNAM, México, DF. 66 p. [ Links ]

Feria A., T. P. 2001. Patrones de distribución de las aves residentes de la Cuenca del Balsas. Tesis de Maestría, UNAM, México, DF. 83 p. [ Links ]

Feria A., T.P. & A.T. Peterson. 2002. Prediction of bird community composition based on point-occurrence data and inferential algorithms: a valuable tool in biodiversity assessments. Divers. Distrib. 8: 49-56. [ Links ]

Gaston, K.J. 1996. The multiform of the interespecific abundant-distribution relationship. Oikos 75: 211-220. [ Links ]

Guizar N., E. & A. Sánchez. 1991. Guía para el reconocimiento de los principales árboles del Alto Balsas. Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, México, DF. 144 p. [ Links ]

Hutto, R. L. 1984. Winter habitats distribution of migratory land birds in western México, with special reference to small foliage gleaning insectivores, p. 48-58. In A. Keast & E.S. Morton (eds.). Migrant birds neotropics, Smithsonian Institution. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., USA [ Links ]

Howell, S.N. & S. Webb. 1995. A guide to the birds of México and northern Central America. Oxford University, Oxford, England. 851 p. [ Links ]

INEGI. 1987. Síntesis geográfica, nomenclátor y anexo cartográfico del estado de Puebla. Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática, México, DF. 60 p. [ Links ]

Karr, J.R. 1981. Seasonal changes in detection of individual bird species. In C.J. Ralph & J.M. Scott (eds.). Estimating the numbers of terrestrial birds. Stud. Avian Biol. 6: 548-553. [ Links ]

Karr, J.R., S.K. Robinson, J.G. Blake & R.O. Bierregaard, Jr. 1990. Birds of four Neotropical forests, p. 237- 269. In A. Gentry, (ed.). Four Neotropical forest Yale University, New Haven, Connetticutt, USA. [ Links ]

Krebs, C.J. 1978. Ecology. Harper International, New York, New York, USA 753 p. [ Links ]

Levey, D. & F.G. Stiles. 1992. Evolutionary precursors of long-distance migration: resource availability and movement patterns in Neotropical landbirds. Am. Nat. 140: 447-476. [ Links ]

Loiselle, B.A. & J.G. Blake. 1992. Population variation in a tropical bird community. Bioscience 11: 838-845. [ Links ]

MacArthur, R.H. & E.O. Wilson. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton University, Princeton, USA. 203 p. [ Links ]

Magurran, E.A. 1988. Ecological diversity and its measurement. Princeton University, Princeton, USA. 179 p. [ Links ]

Maldonado-Coelho, M. & M.Ä. Marini. 2004. Mixed-species bird flocks from Brazilian Atlantic forest: the effects of forest fragmentation and seasonality on their size, richness and stability. Biol. Cons. 116: 19-26. [ Links ]

Malizia, L.R. 2001. Seasonal fluctuations of birds, fruits, and flowers in a subtropical forest of Argentina. Condor 103: 45-61. [ Links ]

Martín del Campo, R. 1937. Contribución al conocimiento de la Ornitología del Estado de Morelos. Anales Inst. Biol. UNAM 8: 333-342. [ Links ]

McGarigal, K.J. & W.C. McComb. 1995. Relationships between landscape structure and breeding birds in the Oregon coast range. Ecol. Monogr. 65: 235-260. [ Links ]

Navarro S., A. 1998. Distribución geográfica y ecológica de la avifauna del Estado de Guerrero, México. Tesis de Doctorado, UNAM, México, DF. 182 p. [ Links ]

Navarro S., A. & H. Benítez. 1993. Patrones de riqueza y endemismo de las aves. Ciencias 7: 45-53. [ Links ]

Ornelas, J.F., M.C. Arizmendi, L. Márquez-Valdelamar, L. Navarijo & H. Berlanga. 1993. Variability profiles for line transect bird censuses in a tropical dry forest in México. Condor 95: 422-441. [ Links ]

Ornelas, J.F. & M.C. Arizmendi. 1995. Altitudinal migration: implication for the conservation of the neotropical migrant avifauna of Western México, p. 98-112. In M.H. Wilson & S.A. Sader (eds.). Conservation of neotropical migratory birds in México. Miscellaneus, Maine, USA. [ Links ]

Ortiz-Pulido, R., H. Gómez, F. González-García & A. Álvarez. 1995. Avifauna del Centro de Investigaciones Costeras La Mancha, Veracruz, México. Acta Zool. Mex. 66: 87-118. [ Links ]

Peterson, R.T. & E.L. Chalif. 1994. Aves de México: Guía de campo. Diana, México, DF. 473 p. [ Links ]

Powell, G.V.N. 1989. On the possible combination of mixed species flocks to species richness in tropical avifaunas. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 24: 387-393. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Albores, J.E. 2000. Estudio de la avifauna en 10 localidades del sureste de Morelos y en 7 localidades del suroeste de Puebla. Tesis de Licenciatura, UNAM, México, DF. 74 p. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Albores, J.E. & G. Ramírez. 2002. Avifauna de la región oriente de la sierra de Huautla, Morelos, México. Anales Inst. Biol. Univ. Nac. Autón. Méx. Ser. Zool. 73: 91-111. [ Links ]

Rojas, O. R. 1995. Riqueza y distribución de las aves del estado de Puebla. Tesis de Licenciatura, UNAM, México, DF. 126 p. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 1978.Vegetación de México. Limusa, México, DF. 432 p. [ Links ]

Stiles, F.G. 1983. Check-list of birds, p. 502-543. In D.H. Janzen (ed.). Costa Rican Natural History. University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA. [ Links ]

Sutton, G.M. & T.D. Burleigh. 1942. Birds recorded in the Federal District and States of Puebla and México by the 1939 sample expedition. Auk 49: 418-423. [ Links ]

Terborgh, J., S.K. Robinson, T.A. Parker III, C.A. Munn & N. Pierpont. 1990. Structure and organization of an Amazonian forest bird community. Ecol. Monogr. 60: 213-238. [ Links ]

Wege, D.C. & A.J. Long. 1995. Key areas for threatened birds in the Neotropics. Birdlife Conservation. Series No. 5, Cambridge, England. [ Links ]

Wilson, M.F. & T.A. Comet. 1996. Bird communities of northern forest: ecological correlates of diversity and abundance in understory. Condor 98: 350-362. [ Links ]

Internet reference

WWF (World Wildlife Fund). 2001. Balsas Dry Forest (NT0205). World Wildlife Found, USA. (Downloaded: http://www.worldwildlife.org/wildworld/profiles/terrestrial/nt/nt0205_full.html). [ Links ]