Revista de Biología Tropical

versión On-line ISSN 0034-7744versión impresa ISSN 0034-7744

Rev. biol. trop vol.52 supl.1 San José sep. 2004

in the Gulf of California, Mexico

I. Gárate-Lizárraga1 , D.J. López-Cortes2 , J.J. Bustillos-Guzmán2 & F. Hernández-Sandoval2

1 Departamento de Plancton y Ecología Marina (CICIMAR-IPN). Apdo. Postal 592, La Paz, Baja California Sur 23000, México; igarate@ipn.mx

2 Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste (CIBNOR). Apdo. Postal 128, La Paz, Baja California Sur 23000, México.

Recibido 31-X-2002. Corregido 14-VII-2003. Aceptado 11-XII-2003.

Abstract

Cochlodinium polykrikoides was the species responsible for the discoloration that occurred between September 15th and 27th , 2000 in a shallow coastal lagoon located in the southern part of the Bahía de La Paz, on the west side of the Gulf of California. Blooms of C. polykrikoides were observed four days after two rainy days with a seawater temperature of 29 to 31°C. Nutrient concentration ranges during the bloom were 0.165- 0.897 µM NO2 +NO3 , 0.16-3.25 µM PO4 , and 1.0-35.36 µM SiO4 . Abundance of C. polykrikoides ranged from 360 x 103 to 7.05 x 106 /cells l-1 . Biomass expressed in terms of chlorophyll a was high, ranging from 2.7 to 56.8 mg/m3 . A typical dinoflagellate pigment profile (chlorophyll a and c, peridinin, diadinoxantin, and b -carotene) was recorded. In this study, the red tide occurred in front of several fish and shrimp-culture ponds. No PST toxins were found in the samples. However, 180 fish were found dead in the infected fish-pond; the gills were the most affected part. C. polykrikoides is a cyst-forming species that recurs in this area. New blooms were observed in November 2000 and September-November 2001 in the same area. Anthropogenic activities, such as eutrophication caused by water discharge in this shallow lagoon, and nutrient enrichment in the culture ponds, as well as effects from precipitation and wind stress, could have favored the outbreak of this dinoflagellate.

Key words: Cochlodinium polykrikoides, blooms, caged fish mortality, Bahía de La Paz, Gulf of California.

Palabras clave: Cochlodinium polykrikoides, proliferaciones, mortalidad de peces en cautiverio, Bahía de la Paz, Golfo de California.

According to Hallegraeff (1993), a world-wide increase of algal blooms has occurred near the end of the 20th century. This increase has also been observed in México, particularly on the eastern shoreline of the Gulf of California, where bloom-forming species have been recorded for the first time (Cortés-Altamirano and Alonso-Rodriguez 1997). For the western shoreline of the Gulf of California, few algal blooms have been reported. The main blooming species are the photothropic protozoan Mesodinium rubrum Lohmann 1908, the dinoflagellates Scrippsiella trochoidea (Stein) Loeblich III 1976 and Noctiluca scintillans (Macartney) Kofoid et Swezy 1920 (Gárate-Lizárraga et al. 2001, 2002), and recently the diatoms Rhizosolenia debyana Peragallo 1892 (Gárate-Lizárraga et al. 2003) and Chaetoceros debilis Cleve 1894. Cochlodinium polykrikoides Margalef 1961 is a bloom dinoflagellate newly reported for this area (Gárate-Lizárraga et al. 2000), whose distribution is restricted to warm and tropical waters (Steidinger and Tangen 1996). Blooms caused by C. polykrikoides have been associated with massive fish kills, and is regarded as a potentially toxic dinoflagellate in Korea (Kim 1997). The purpose of this paper is to understand environmental conditions where C. polykrikoides proliferate in a shallow coastal lagoon located in the southwest coast of the Gulf of California.

Materials and methods

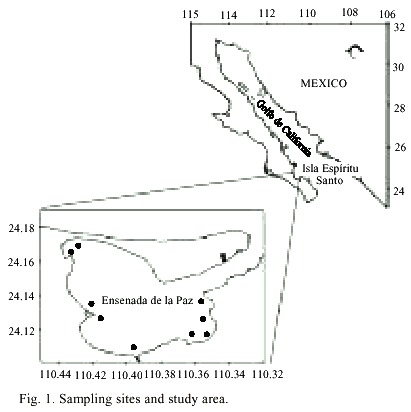

From September 15th to 28th 2000, several red patches were observed in the inner part of the coastal lagoon, La Ensenada de La Paz (24.13° N, 110.39° W) (Fig. 1). Samples of these patches were collected near the surface and fixed with a few drops of lugol. Live cells were used for proper identification. Water samples were also taken with Van Dorn bottles for the determination of nutrients (NO3 , NO2 , PO4 , SiO2 ) and photosynthetic pigments. Seawater temperature was measured with a thermometer (Kahlsico). Nitrates, nitrites, phosphates, and silicates were measured according to Strickland and Parson (1972). Cell counts were performed in 5 ml settling chambers, using a phase contrast inverted microscope. The photosynthetic pigments were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (Vidussi et al. 1996). Identification and quantification of pigments were made, as described in Bustillos-Guzmán et al. (1995). Because paralytic shellfish toxins (PST) have been reported for Cochlodinium type-78 Yatsushiro (Onoue and Nosawa 1989), PST analysis was performed. Samples from a red tide of C. polykrikoides were collected for toxin analysis and were filtered through GF/F Whatman filters, frozen, and a post-column oxidation and fluorescence detection system (Hummer et al. 1997, Yu et al. 1998). Precipitation data were obtained from the Comisión Nacional del Agua (CNA), México. Recurrent blooms were observed during November 2000 and September-November 2001. Samples for identification purposes were taken in these last episodes, which started in the same area that had previous outbreaks and had expanded to Bahía de La Paz and the area near Isla Espíritu Santo (Fig. 1).

Results

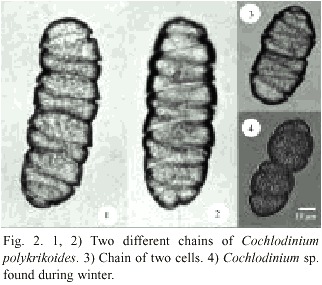

C. polykrikoides was the species responsible for seawater discoloration that occurred from September 15 th to 27 th , 2000 in La Ensenada de La Paz. Most specimens of C. polykrikoides were forming chains of four organisms and rarely of two cells. C. polykrikoides is an unarmored, marine, planktonic dinoflagellate with a distinctive spiral-shaped cingulum, which is deep and excavated (Fig. 2) and occupies an area about 0.6 times the cell length, and descends in a distinct left-handed spiral of 1.8-1.9 turns around the cell. Cells range in size from 30-42 µm in length and 22-30 µm in width. A red stigma was observed dorsally in the epitheca.

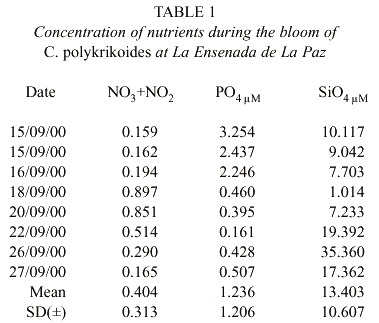

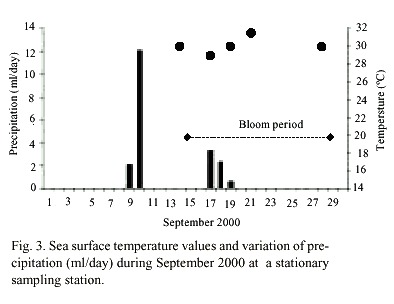

C. polykrikoides blooms were observed four days after two days of rain. The reddish patches were found mainly in the shallow areas (1-4 m to bottom), and they occurred where water temperature ranged from 29 to 31°C (Fig. 3). Nutrient concentrations during the bloom ranged from 0.165-0.897 µM NO2 +NO3 , 0.16-3.25 µM PO4 , and 1.0- 35.36µM SiO4 (Table 1).

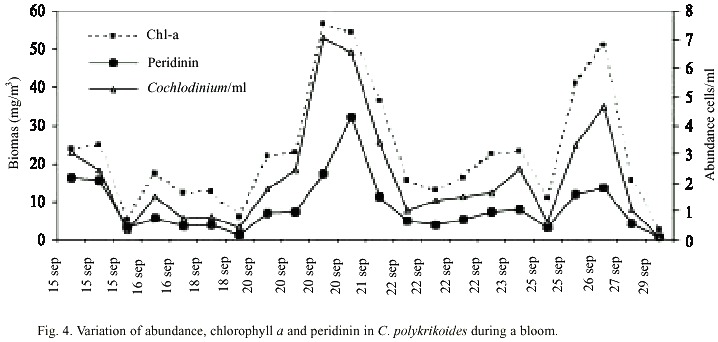

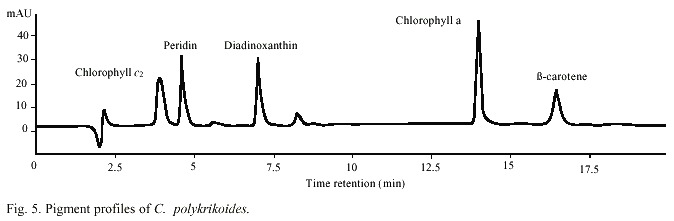

Abundance of C. polykrikoides ranged from 360 x 103 to 7.05 x 106 /cells l-1 (Fig. 4). Biomass, expressed in terms of chlorophyll ranged from 2.7 to 56.8 mg/m3 , and the carotenoid dinoflagellate fingerprint, the peridinin, ranged from 0.68 to 32.03 mg/m3 (Fig. 4). A typical dinoflagellate pigment profile (chlorophyll a and c, peridinin, diadinoxantin, and b -carotene) was observed in C. polykrikoides (Fig. 5).In this investigation, no PST toxins were found in samples of C. polykrikoides. The algal extracts did not showed any peaks corresponding to PST on the HPLC chromatograms. During the first outbreak, 27 dead pargo fish (Lutjanus argentiventis Peters 1869) were found in the infected fish pond, with only their gills infected. In the outbreak occurring in September-November 2001, about 180 caged fish died (60 adult Pomadasys macracanthus (Hunter) Jordan 1888; 90 juvenile and 20 adult Diapterus peruvianus Cuvier 1830, and 10 adult L. argentiventis).

Discussion

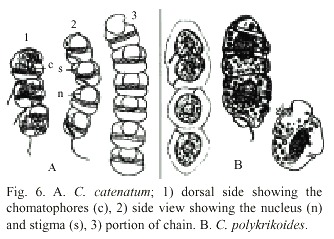

C. polykrikoides is an unarmored, marine, planktonic dinoflagellate. This species is synonymous with C. heterolobatum Silva (Silva 1967). Proper identification of C. polykrikoides was difficult because this species became rounded, contracted, or disrupted with the fixative agent (lugol). Hallegraeff and Fraga (1996) and Cho et al. (2001) mentioned that C. polykrikoides can be mistaken for Gymnodinium catenatum Graham 1943 and Gyrodinium impudicum Fraga and Bravo 1995. Cortés-Altamirano and Alonso-Rodríguez (1997) recorded several blooms of G. catenatum during Autumn 1997 in Bahía de Mazatlán and later re-identified it as G. impudicum (Cortés-Altamirano et al. 1999). Cortés-Altamirano (2002) again re-identified this species as Cochlodinium catenatum. In this study, we used the description of Margalef (1961) to identify C. polykrikoides, as well as Fukuyo et al. (1990) and Steidinger and Tangen (1996). Fig. 6 shows original drawings of C. catenatum and C. polykrikoides made by Okamura (1916) and Margalef (1961). The epicone of C. catenatum is anteriorly subhemispherical and the epicone of C. polykrikoides is "cupuliform". The principal difference between them is the presence of stigma. Margalef (1961) reported only one large and complex stigma and Okamura (1916) reported some small reddish stigma. Description of Cochlodinium found in our study coincides with Margalef´s description. Genetic studies are recommended to clearly separate this two species or re-instate C. polykrikoides to C. catenatum, which was described first.

Distribution of both Cochlodinium species is quite similar. C. catenatum is distributed in Japan (Okamura 1916), California (Kofoid and Swesy 1921, Venrick 2000), Costa Rica, and Panamá (Guzmán et al. 1990) where it was implicated in coral mortality. C. polykrikoides is distributed in Puerto Rico (Margalef 1961), Chesapeake Bay, Barnegat Bay, New Jersey (Silva 1967), York River, Virginia (Ho and Zubkoff 1979), Japan (Fukuyo et al. 1990), Guatemala (Rosales-Loessener et al. 1996), Korea (Kim 1998, Kim et al. 1999), and now in the Gulf of California.

Although these two blooms are the only records of this species in the Gulf of California, the genus Cochlodinium was firstly recorded in samples collected in January 1942 (Osorio-Tafall 1943). Likewise, Morey-Gaines (1982) reported concentrations of 100 x 103 Cochlodinium/l-1 during a red tide of G. catenatum in Bahía de Mazatlán in April 1979. Along the Manzanillo coast (state of Colima), some red tides of C. polykrikoides were reported by Morales-Blake and Hernández-Becerril (2001). Gárate-Lizárraga et al. (2004) found these two species occurring in samples collected in Bahía de Mazatlán in April 2001. The lack of records of Cochlodinium in previous works may result from using formaldehyde and lugol, which are not good fixatives (Osorio-Tafall 1943, Gárate-Lizárraga et al. 2000, Figueroa-Torres y Zepeda-Esquivel 2001). Recent observations of live phytoplankton from Bahía de La Paz confirm the presence of other Cochlodinium species such as C. schuetti Kofoid et Swezy 1921 and C. citron Kofoid et Swezy 1921 through the year.

Both C. polykrikoides abundance (360 x 103 to 7.05 x 106 /cells l-1 ) and chlorophyll a concentrations (2.7 to 56.8 mg/m3 ) were closely related. These biomass concentrations are the highest recorded in the area. Highest values of chlorophyll a, up to 10 mg/m3 , have been reported and related to blooms of the protozoan Mesodinium rubrum (Martínez-López et al. 2001), which seem to be very common in this area (Gárate-Lizárraga et al. 2001). Highest values of chlorophyll a (17.15 to 41.45 mg/m3 ) have been also reported for exceptional blooms of the diatom Rhizosolenia debyana (Gárate-Lizárraga et al. 2003). Blooms of C. polykrikoides could be also responsible for local increases in the concentrations of chlorophyll a, and seem to be very important in terms of the fertility of the coastal zone.

Jeong et al. (2001) found the presence and persistence of C. polykrikoides in lower (20°C) and higher (28°C) water temperatures, however, those outbreaks were mainly associated with a lower temperature (25-26°C). C. polykrikoides blooms reported here occurred at a higher range (29 to 31°C) and salinities between 28.94 to 32.5 psu. In general, our findings of nutrient concentrations coincide with those found by Lechuga-Devéze et al. (1997) and Cervantes-Duarte et al. (2001) for mid-summer (August-September). However, at the beginning of this red tide caused by C. polykrikoides, phosphates were higher (2.24-3.25 µM) than found in previous studies. This could be a result of the preceding rainy days, which contributed the phosphates in runoff. These concentrations are in the range considered characteristic of eutrophic waters in Bahía de Mazatlán, which is influenced by municipal sewage effluent (Alonso-Rodríguez et al. 2000).

Intensive aquaculture has contributed to eutrophication in some coastal areas. It is probable that nutrients close to shrimp culture ponds during a post-harvest period were unloaded into La Ensenada de la Paz. These eutrophic environments are very susceptible to harmful algal blooms (Kim 1998). Further, nutrient accumulation near the culture ponds can be moved by the action of the local winds and runoff from heavy rains. Anthropogenic activities, such as eutrophication caused by water discharged into La Ensenada de La Paz and nutrient enrichment in the culture ponds, as well as effects of precipitation and wind, could have favored the outbreak of this dinoflagellate. C. polykrikoides is a cyst-forming species (Matsuoka and Fukuyo 2000) that is recurrent, and it is plausible that this is the cause of the blooms observed in November 2000 and September-November 2001. Moreover, after Hurricane "Juliette," C. polykrikoides expanded to Bahía de La Paz and off Isla Espiritu Santo from September 26th to November 4th , 2001.

Blooms of C. polykrikoides occurring in Japan have provoked massive death in fish populations (Yuki and Yoshimatsu 1989, Kim 1998). In Costa Rica and Panama, blooms of C. catenatum were implicated in coral mortality, which was partly attributed to smothering by the mucus produced by the dinoflagellate (Guzmán et al. 1990). Recently, a bloom of Cochlodinium in Canada caused substantial mortality to cultured salmon, accounting for economic losses of about CAN$ 2 million (Whyte et al. 2001).

Although we did not find evidence of PST in Cochlodinium samples, death of juvenile and adults fish of L. argentiventis, D. peruvianus, and P. macracanthus was observed. Fish mortality occurs because caged fish have less opportunity to avoid harmful algal blooms than wild fish. Ho and Zubkoff (1979) suggested that physical contact, not a released toxin, was the cause of oyster larvae (Crassostrea virginica Guilding 1828) deformation and mortality during a C. polykrikoides red tide in the York River of Virginia.This dinoflagellate generates reactive oxygen, O-2 , OH, H2 O2 These radicals are factors that can induce fish kills (Kim et al. 1999). Kim et al. (2002) propose that biologically-active multiple metabolites secreted by C. polykrikoides, such as cytotoxic agents and mucus substances, may contribute to fish kills. In this study, the red tide occurred in front of several fish and shrimp-culture ponds. One of them was infected with C. polykrikoides, reaching abundances of 8 x 106 /cells l-1 . Fishes were examined and gill damage was observed.

Hydrological and phytoplankton monitoring programs are necessary to help prevent future mass kills of marine animals, particularly caged species of economic value. Adequate water quality will be necessary to achieve sustainability of coastal ecosystems. Insight into the mechanisms that determine lethal species composition is needed to predict the possible effect of water quality.

Acknowledgments

Partial financial support was provided by the CONACYT grant 138138 and the CIBNOR projects GEA-3 and AYCG-11. Other support came from the IPN projects DEGEPI 990318 and 200203333). We are grateful to I. Murillo and B. López-Bustamante, (CIBNOR) for nutrients and pigment analyses, Juan Carlos Pérez (CIBNOR) for temperature and fish mortality data; Katrin Reinhardt (University of Jena) for PST analyses; Carmelo Thomas (Center for Marine Science, the University of North Carolina at Wilmington) for precise identification of C. polykrikoides; editing staff at CIBNOR for modifying the English text. I. Gárate-Lizárraga has COFAA and EDI fellowships.

Resumen

Durante el desarrollo de una marea roja ocurrida del 15 al 27 de septiembre del año 2000 en la Ensenada de La Paz, B.C.S. se tomaron muestras de agua con una botella Van Dorn para determinar la temperatura, la especie causante y la cantidad de nutrientes y pigmentos fotosintéticos. Se hicieron análisis de toxinas de Cochlodinium polykrikoides, la especie responsable de esta marea roja. La mayoría de los especimenes formaron cadenas de cuatro células y raramente de dos. La abundancia fue de 360 x 103 a 7.05 x 106 /cels l-1 . Los florecimientos de C. polykrikoides ocurrieron cuatro días después de dos días lluviosos; el intervalo de temperatura fue de 29 a 31°C. La concentración de nutrientes registrada durante este fenómeno fue 0.165-0.897 µM NO2 +NO3 , 0.16-3.25 µM PO4 , y 1.0-35.36 µM SiO4 . El perfil pigmentario reveló la presencia de clorofila a y c, peridinina, diadinoxantina, y b -caroteno. La biomasa total expresada en clorofila a fue alta, oscilando entre 2.7 y 56.8 mg/m3 , mientras que la biomasa de Cochlodinium, expresada en peridinina, varió entre 0.68 y 32.03 mg/m3 . En este estudio, la marea roja se desarrolló cerca de varios estanques de cultivo de peces y camarón. En uno de ellos proliferó C. polykrikoides. Los análisis de toxinas PST fueron negativos; sin embargo, durante el incremento de las proliferaciones algunos estanques fueron alcanzados y murieron 180 peces, principalmente pargos (Lutjanus argentiventis, Pomadasys macracantus). Las branquias fueron las partes más afectadas. En condiciones desfavorables C. polykrikoides forma quistes, lo cual ha provocado su recurrente proliferación en el área, registrándose nuevas proliferaciones en noviembre del 2000 y en septiembre-noviembre del 2001. Actividades antropogénicas como la eutroficación causada por la descarga de aguas residuales y de nutrientes de los estanques de cultivo, pudieran estar favoreciendo la proliferación de este dinoflagelado.

References

Alonso-Rodríguez, R., F. Páez-Osuna & R. Cortés-Altamirano. 2000. Trophic Conditions and Stoichiometric Nutrient Balance in Subtropical Waters Influenced by Municipal Sewage Effluents in Mazatlán Bay (SE Gulf of California). Mar. Poll. Bull. 40: 331-339. [ Links ]

Bustillos-Guzmán, J., H. Claustre & J.C. Marty. 1995. Specific phytoplankton signatures and their relationship to hydrographic conditions in the coastal northwestern Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 124: 247-258. [ Links ]

Cervantes-Duarte, R., F. Aguirre-Baena, A. Reyes-Salinas, & J.E. Valdéz-Holguín. 2001. Caracterización hidrológica de una laguna costera de Baja California Sur, México. Oceánides. 16: 1-11. [ Links ]

Cho, E.S., G.Y. Kim, B.D. Choi, L.L. Rhodes, T.J. Kim, G.H. Kim & J.D. Lee. 2001. A comparative study of the harmful dinoflagellates Cochlodinium polykrikoides and Gyrodinium impudicum using transmission electron microscopy, fatty acid composition, carotenoid content, DNA quantification and gene sequences. Bot. Mar. 44: 57-66. [ Links ]

Cortés-Altamirano, R. 2002. Mareas rojas: biodiversidad de microbios que pintan el mar, pp. 29-41. In J.L. Cifuentes & J. Gaxiola López (eds.). Atlas de Biodiversidad de Sinaloa. Colegio de Sinaloa. [ Links ]

Cortés-Altamirano, R. & R. Alonso-Rodríguez. 1997. Mareas rojas durante 1997 en la Bahía de Mazatlán, Sinaloa, México. Cien. Mar. 15: 31-37. [ Links ]

Cortés-Altamirano, R., A. Núñez-Pasten & N. Pasten-Miranda. 1999. Abundancia anual de Gymnodinium catenatum Graham dinoflagelado tóxico de la costa Este del Golfo de California. Cien. Mar. 3: 50-56. [ Links ]

Figueroa-Torres, M.G. & M.A. Zepeda-Esquivel. 2001. Mareas Rojas del Puerto Interior, Colima, México. Sci. Nat. 3: 39-51. [ Links ]

Fraga, S., I. Bravo, M. Delgado, J.M. Franco & M. Zapata. 1995. Gyrodinium impudicum sp. nov. (Dinophyceae), a non toxic, chain-forming, red tide dinoflagellate. Phycologia 34: 514-521. [ Links ]

Fukuyo, Y., H. Takano, M. Chihara & K. Matsuoka 1990. Red tide organisms in Japan. An illustrated taxonomic guide. Uchida Rokakuho, Tokyo. 407 p. [ Links ]

Gárate-Lizárraga, I., J.J. Bustillos-Guzmán, L.M. Morquecho & C.H. Lechuga-Deveze. 2000. First outbreak of Cochlodinium polykrikoides in the Gulf of California. Harmful Algae News 21: 7. [ Links ]

Gárate-Lizárraga, I., M.L. Hernández-Orozco, C. Band-Schmidt & G. Serrano-Casillas. 2001. Red tides along the coasts of the Baja California Sur, México (1984 to 2001). Oceánides 16: 127-134. [ Links ]

Gárate-Lizárraga, I., C. Band-Schmidt, R. Cervantes-Duarte & D.G. Escobedo-Urías. 2002. Mareas rojas de Mesodinium rubrum (Lohmann) Hamburger y Budenbrock ocurridas en el Golfo de California durante el invierno de 1998. Hidrobiológica 12: 15-20. [ Links ]

Gárate-Lizárraga, I. & D.A. Siqueiros-Beltrones. 2003. Infection of Ceratium furca by the parasitic dinoflagellate Amoebophrya ceratii (Amoebophryidae) in the Mexican Pacific. Acta Bot. Mex. 65: 1-9. [ Links ]

Gárate-Lizárraga, I., D.A. Siquieros Betrones & V. Maldonado-López. 2003. First record of a Rhizosolenia debyana bloom in the Gulf of California, Mexico. Pac. Sci. 57: 141-145. [ Links ]

Gárate-Lizárraga, I., J.J. Bustillos-Guzmán, R. Alonso-Rodríguez & B. Luckas. 2004. Comparative paralytic shellfish toxin profiles in two marine bivalves during outbreaks of Gymnodinium catenatum (Dinophyceae) in the Gulf of California. Mar. Poll. Bull. 48: 397-492. [ Links ]

Guzmán, H.M., J. Cortés, P.W. Glynn & R.H. Richmond. 1990. Coral mortality associated with dinoflagellate blooms in the eastern Pacific (Costa Rica and Panama). Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 60: 299-303. [ Links ]

Hallegraeff, G.A. 1993. Areview of harmful algal blooms and their apparent global increase. Phycologia 32: 79-99. [ Links ]

Hallegraeff, G.M. & S. Fraga. 1996. Bloom dynamics of the toxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum, with emphasis on Tasmanian and Spanish coastal waters, pp. 59-80. In D.M. Anderson, A.D. Cembella & G.M. Hallegraeff (eds.). Physiological Ecology of Harmful Algal Blooms NATO ASI Series. [ Links ]

Ho, M.S. & P.L. Zubkoff. 1979. The effects of a Cochlodinium heterolobatum bloom on the survival and calcium uptake by larvae of the American oyster, Crassostrea virginica, pp. 409-412. In F.J.R. Taylor & H.H. Seliger (eds.). Toxic Dinoflagellate Blooms. New York. [ Links ]

Jeong, H.D., H.G. Kim, B.K. Kim, K.D. Cho & J.D. Hwang. 2001. The prediction and movement of the harmful algal blooms in Korean waters. PICES Program abstracts, Victoria, B.C. Canada. pp. 108. [ Links ]

Kim, H.G. 1997. Recent Red Tides in Korean Coastal Waters. Ocean Res. 19: 185-192. [ Links ]

Kim, H.G. 1998. Cochlodinium polykrikoides blooms in Korean coastal waters and their mitigation, pp. 227- 228. In B. Reguera, J. Blanco, T. Fernández & Wyatt (eds.). Harmful Algae, Xunta de Galicia and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO. [ Links ]

Kim, C.S., S.G. Lee, C.Y. Lee & H.G. Kim. 1999. Reactive oxygen species as causative agents in the ichthyo-toxicity of the red tide dinoflagellate Cochlodinium polykrikoides. J. Plank. Res. 1: 2105-2115. [ Links ]

Kim, D., T. Oda, T. Muramatsu, D. Kim, Y. Matsuyama & T. Honjoc. 2002. Possible factors responsible for the toxicity of Cochlodinium polykrikoides, a red tide phytoplankton. Comp. Bioch. Physiol. Part C. 132: 415-423. [ Links ]

Kofoid, C.A. & O. Swezy. 1921. The free-living unarmo-red Dinoflagellata. Mem. Univ. Calif. 5: 1-564 [ Links ]

Lechuga-Deveze, C., I. Murillo-Murillo, F. Hernández-Sandoval & R.A. Mendoza-Salgado. 1997. Influencia de drenaje de estanques de cultivo de camarón sobre las características físicas y químicas de las aguas de mar adyacentes. Hidrobiológica 7: 27-32. [ Links ]

Margalef, R. 1961. Hidrografía y fitoplancton de un área marina de la costa meridional de Puerto Rico. Inv. Pesq. 18: 76-89. [ Links ]

Martínez-López, A., R. Cervantes-Duarte, A. Reyes-Salinas & J.E. Valdez-Holguín. 2001. Cambio estacional de la clorofila a en la Bahía de La Paz, B.C.S., México. Hidrobiológica 11: 230-241. [ Links ]

Matsuoka, K. & Y. Fukuyo. 2000. Guía técnica para el estudio de quistes de dinoflagelados actuales. HAB/WESTPAC/IOC, Japan. 30 p. [ Links ]

Morales-Blake, A. & D.U. Hernández-Becerril. 2001. Unusual HABs in Manzanillo Bay, Colima, México. Harmful Algae News, 21: 6. [ Links ]

Morey-Gaines, G. 1982. Gymnodinium catenatum Graham (Dinophyceae): morphology and affinities with others armoured forms. Phycologia 21: 154-163. [ Links ]

Okamura, K. 1916. An annotated list of plankton microorganisms of the Japanese coast. Annot. Zool. Japan 6: 125-151. [ Links ]

Onoue, Y. & K. Nozawa. 1989. Separation of toxins from harmful red tides occurring along the coast of Kagoshima prefecture, pp. 371-374. In T. Okaichi, D.M. Anderson, T. Nemoto. (eds.). Red tides: Biology, Environmental Science, and Toxicology. Elsevier, New York. [ Links ]

Osorio-Tafall, B.F. 1943. El Mar de Cortés y la productividad fitoplanctónica de sus aguas. Anal. Esc. Nal. Cien. Biol. 3: 13-118. [ Links ]

Park, J.G., M.K. Jeong, J.A. Lee, K.J. Cho & O.S. Kwon. 2001. Diurnal vertical migration of a harmful dinoflagellate, Cochlodinium polykrikoides (Dinophyceae), during a red tide in coastal waters of Namhae Island, Korea. Phycologia 40: 292-297. [ Links ]

Rosales-Loessener, F., K. Matsuoka, Y. Fukuyo & E.H. Sánchez. 1996. Cyst of harmful dinoflagellates found from Pacific Central waters of Guatemala, pp. 193-195. In T. Yasumoto, Y. Oshima, Y Fukuyo. (eds.). Harmful and Toxic Algal Blooms. IOC-UNESCO, Paris. [ Links ]

Silva, E.S. 1967. Cochlodinium heterolabatum nov. sp.: Structure and some cytophysiological aspects. J. Protozool. 14: 745-754. [ Links ]

Steidinger, K.A. & K. Tangen. 1996. Dinoflagellates, pp. 387-584. In C.R. Tomas (ed.). Identifying marine diatoms and dinoflagellates. Academic, San Diego. [ Links ]

Strickland, J.D. & R. Parsons. 1972. A practical handbook of seawater analysis. Fish. Res. Bd. Can. Bull. 167: 207-211. [ Links ]

Yu, R.C., C. Hummert, B. Luckas, P.Y. Qian & M.J. Zhou. 1998. Modified HPLC method for analysis of PST toxins in algae and shellfish from China. Chromatography 48: 671-676. [ Links ]

Yuki, K. & S. Yoshimatsu. 1989. Two fish-killing species of Cochlodinium from Harima Nada, Seto Inland Sea, Japan, pp. 11-16. In Okaichi, Anderson & Nemoto (eds.). Red Tides: Biology Environmental Science and Toxicology. Elsevier, New York. [ Links ]

Venrick, L.E. 2000. Summer in the Ensenada Front: The distribution of phytoplankton species, July 1985 and September 1988. J. Plank. Res. 22: 813-841. [ Links ]

Vidussi, F., H. Claustre, J. Bustillos-Guzmán, C. Cailleau & J.C. Marty. 1996. Rapid HPLC method for determination of phytoplankton chemotaxonomic pigments: separation of chlorophyll a from divinyl-chlorophyll a and zeaxanthin from lutein. J. Plank. Res. 18: 2377-2382. [ Links ]

Whyte, I., N. Haigh, N.G. Ginther & L.J. Keddy. 2001. First record of blooms of Cochlodinium sp. (Gymnodiniales, Dinophyceae) causing mortality of net-pen reared salmon on the west coast of Canada. Phycologia 40: 298-304. [ Links ]

uBio

uBio