Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO  uBio

uBio

Share

Revista de Biología Tropical

On-line version ISSN 0034-7744Print version ISSN 0034-7744

Rev. biol. trop vol.49 n.3-4 San José Dec. 2001

and HLA-DQA1 loci

Bernal Morera 1-2 *, Gerardo Sánchez-Rivera 3 , Gerardo Jiménez-Arce 2-4 , Francesc Calafell 1, and Ana Isabel Morales-Cordero 3

1 Unitat de Biología Evolutiva, Departamento de Ciencias de la Salud y de la Vida, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, 08003 Barcelona, España. Fax: +34-93.542.28.02.

2 Genómica Int., San José, Costa Rica.

3 Unidad de ADN, Sección de Bioquímica, Organismo de Investigación Judicial, Poder Judicial, Heredia, Costa Rica.

4 CIHATA, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica.

* Corresponding author: Bernal Morera. c. Instituto Clodomiro Picado, Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica. Corel: rbt@cariari.ucr.ac.cr bmorera@costarricense.cr

Received 22-III-2001. Corrected 05-IX-2001. Accepted 06-IX-2001.

Abstract

Nicaraguans have become the most numerous and fastest increasing minority in Costa Rica: at present they represent around 6 % of the total population of the country. We have analyzed the allele and genotype frequencies of six PCR-based genetic markers (LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8, GC, and HLA-DQA1) in 100 unrelated Nicaraguans living in Costa Rica. All loci studied were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Some statistical parameters of forensic interest were also calculated (h, PD and CE). Allele frequencies of the markers HLA-DQA1 and GYPAwere found to be significantly different between the populations of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Nevertheless, genetic distances showed that Nicaragua is close to other Hispanic-admixed populations like those from Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and USA Hispanics. The loci set was assessed to be useful for paternity testing and individual identification in the Nicaraguan population residing in Costa Rica.

Key words: PCR-based, LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8, GC, HLA-DQA1, genetic markers, polymorphism, Nicaragua, Costa Rica.

Until a some years ago, the immigrant population formed a very low proportion of the total population of Costa Rica. However, during the last 30 years Nicaraguans in Costa Rica experienced a considerable increase both by immigration and birthrate. Now, at around 6 % of the residing population of the country, they passed from being 1.4 % to becoming the most numerous minority (Schmidt 1979, Chen Mok et al. 2000, Anonymous 2001a).

International standards demand the existence of population-specific data that support the biostatistical calculations in cases when an exclusion can not be achieved, as much in the paternity investigations as in the analyses of biological remains of criminological interest (Carracedo et al. 1997, Anonymous 2000, Gómez and Carracedo 2000). In 1997, the Judicial Branch of Costa Rica introduced DNAtechnology in paternity and forensic testing and, as a result, an extensive study of the distribution of the DNA genetic markers in the Costa Rican population was made possible (Morales-Cordero et al. 2001). The official historiography has presumed, since the last decades of the 19 th century to the present day, that the people in Costa Rica are ethnically different from their neighbors in Nicaragua (Meléndez Obando 1999, Sandoval García 1999, Acuña Ortega 2001, Dobles 2001). However, to the best of our knowledge, the population genetics of the general Nicaraguan nation remains completely unknown.Since the influx of Nicaraguans requiring judicial services for biological analyses is not low, and due to the fact that it occasionally concerns cases of penal character, it became clear the necessity of also knowing the gene frequency distribution of those markers in them. That information is of the utmost importance for an adequate administration of justice. The objective of this study was to analyze the genetic particularities of the Nicaraguan population residing in Costa Rica and to create a reference database to contribute to the resolution of civil and penal cases involving persons of that nationality.

Materials and methods

The loci LDLR, GYPA, D7S8, HBGG, GC, and HLA-DQA1 were analyzed in a sample of 100 adult, unrelated, volunteer donors of both sexes, originating from different regions of Nicaragua and residing in Costa Rica. Informed consent was requested and stored at the "Unidad de ADN, OIJ, Poder Judicial de Costa Rica".

Genomic DNA was isolated from total blood using standard proteinase K-digestion and Chelex extraction (Singer and Tanguay 1989). Amplification was performed in a GeneAmp 9 600 thermocycler. The presence of PCR product was determined with an aliquot in a 1 % agarose minigel in TBE 0.5 X buffer. DNA hybridization and genotyping was performed using the Amplitype PM+HLA-DQA1 kit according to the manufacturers recommendations (Anonymous 1995).

Gene frequencies were determined by gene counting and maximum likelihood methods. We tested the goodness of fit to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium on genotypic data. Some statistical parameters of forensic interest (h, heterozygosity; PD, power of discrimination; and CE, a priori chance of exclusion) were also calculated. Data from Nicaragua and Costa Rica were analyzed for genetic structure by the exact test of population differentiation. Data analyses were performed with the Arlequin program (Schneider et al. 1997). Summary data were banked in the Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Nuclear DNA Database (Alonso and Albarrán 2000, Anonymous 2001b).

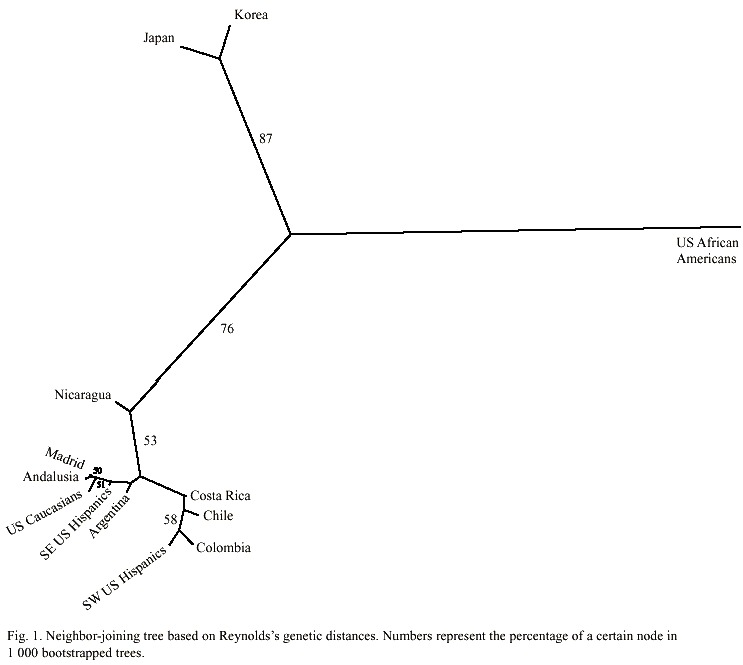

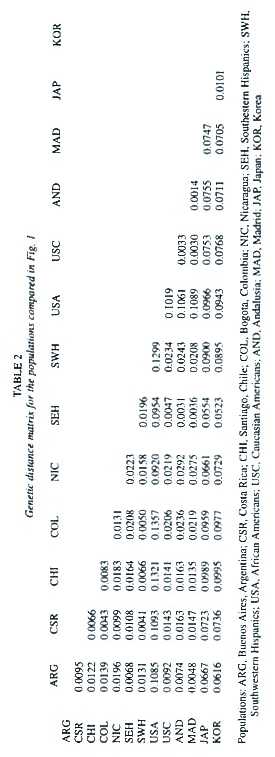

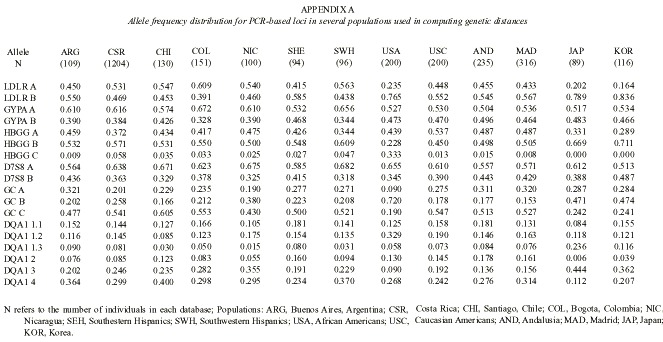

The available information on the allele frequencies of the studied loci was used to estimate the genetic distances between several relevant populations. Seven populations of Hispanic origin in the Americas were included in the analysis: Buenos Aires from Argentina (Padula et al. 1999), Santiago from Chile (Jorquera and Budowle 1998), Bogota from Colombia (Castillo et al. 1996, Terreros-Ibanez et al. 1999), Costa Rica (Morales-Cordero et al. 2001), Nicaragua (this paper), and two Hispanic groups from the USA (Budowle et al. 1995). Two related Spanish populations were considered: Andalusia (Lorente et al. 1997, Anonymous 1998a), and Madrid (Herrera et al. 1996, Anonymous 1998b). Other populations such as Japan (Anonymous 1995), Korea (Woo and Budowle 1995), and Afro-Americans and Caucasians from the USA (Budowle et al. 1995) were also included as reference (Appendix A). An FST –based distance (Reynolds et al. 1983) was computed between every pair of populations. Genetic trees were generated from the distance matrix by means of the neighbor-joining algorithm (Saitou and Nei 1987). A few branches that obtained negative numbers were set to zero. A tree was drawn using the Tree View program (Page 1998). A bootstrap analysis was produced on 1 000 resamples, drawn at random with replacement from the allele set. The standard deviation of these bootstraped distances was used to estimate both the standard error of the genetic distances and tree robustness. Every occurrence of a particular cluster in the tree was recorded and given as a percentage of the 1 000 bootstrap trees. Percentages above 50 % were regarded as indications of the statistical robustness of a cluster. This analysis was done using the PHYLIP 3.5 package (Felsenstein 1989).

Results

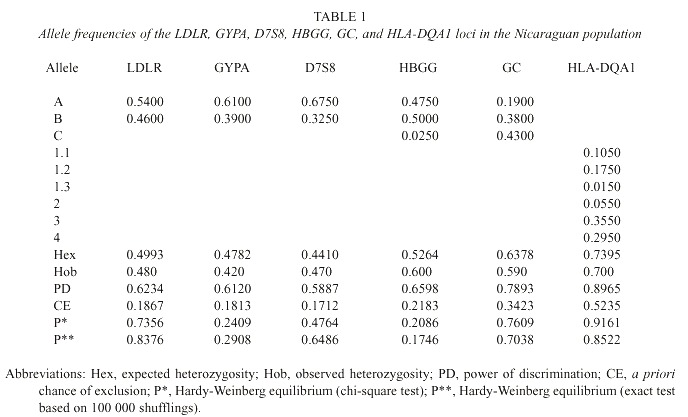

The calculated statistical parameters of forensic interest are shown in Table 1. The studied systems did not reveal any significant deviation to the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. The combined forensic probability of discrimination with those DNA markers is 0.9996, and the probability of excluding a non-father if the mother is known is 0.865.

Significant differences were found between the Nicaraguan and Costa Rican populations (Morales-Cordero et al. 2001) at the HLA-DQA1 and GYPA markers (p < 0.05). However, there were no statistical differences between both populations at the LDLR, HBGG, D7S8, and GC loci.

The genetic distances between the population groups of Hispanic origin from the Americas, the two related groups from Spain, and the other populations used for reference are given in Table 2. All distance values are at least twice their standard errors and thus different from zero. The unrooted tree produced using the neighbor-joining algorithm is shown in Fig. 1. As expected, Afro-Americans split alone like an outgroup, and Japan and Korea formed a cluster together.

All Hispanic-derived populations roughly clustered jointly with the Caucasian populations from Spain and the USA. In this context, the Nicaraguan population was closer to the rest of the admixed populations such as those from Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and the USA Hispanics than to the European, Asiatic, or other American populations.

Discussion

The analyzed loci set was validated as useful for paternity testing and individual identification in the Nicaraguan population residing in Costa Rica, but a study of highly informative loci, like the commercially available short tandem repeats (STRs) is recommended, since the a priori probabilities found were high but could not be sufficient in complex cases such as those involving related individuals.

On the other hand, we chose a neighborjoining reconstruction to analyze the genetic relationships between the Nicaraguan people and their surrounding populations because it leads to unrooted trees, preventing the direct interpretation of the tree as a series of successive fissions from a known starting point. Certainly, this is not the case in the Hispanicderived populations of the Americas, which were mainly established by admixture processes (Sans 2000). It is remarkable that the unrooted tree obtained through neighbor-joining (Fig. 1) does not reflect the geographic location of the populations. This apparent anomaly is clearly observed between the populations of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, which, in spite of their vicinity and close relationship throughout history, do not cluster together. In fact, the Costa Rican nation clustered in the same branch with the populations from Chile, Colombia, and southwestern Hispanics from the USA. It is interesting that all these populations are known to share similar degrees of admixture (Long et al. 1991, Cerda-Flores et al. 1994, Sandoval et al. 1993, Morera and Barrantes 1995, Merriwether et al. 1997, Palomino et al. 1997), a factor that shall be influencing the tree topology. Hence, based on the present data, we hypothesize that the Nicaraguan population has a unique proportion of admixture from the ethnic Amerindian, West African, and Spanish ancestral populations, different from the populations studied this far.

Acknowledgments

We thank the people who participated in the study, without whose cooperation this work would have not been possible. We are indebted to María Santos for her valuable help. This research was carried out at the "Poder Judicial de Costa Rica". B.M. and G.J. were granted by the CGP Foundation. B.M. received a fellowship from the "Agencia Española de Cooperación Internacional" (AECI). A.I.M received a fellowship from the "Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología de Costa Rica".

Resumen

Los nicaragüenses se han convertido en el grupo minoritario más numeroso y creciente en Costa Rica y en la actualidad representan alrededor del 6 % de la población total del país. Analizamos las frecuencias alélicas y genotípicas de seis marcadores genéticos (LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8, GC y HLA-DQA1) basados en la PCR en 100 nicaragüenses no emparentados, residentes en Costa Rica. Todos los loci estudiados cumplieron con el equilibrio de Hardy-Weinberg. También se calcularon algunos parámetros estadísticos de interés forense (h, PD y EC). Se encontró que las frecuencias alélicas de los marcadores HLA-DQA1 y GYPA presentan diferencias significativas entre las poblaciones de Nicaragua y Costa Rica. Sin embargo, el análisis de distancias genéticas mostró que la población de Nicaragua es cercana a otras de origen hispano mestizo como las poblaciones de Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica y los hispanos de Estados Unidos. Este conjunto de loci fue validado como útil para la realización de pruebas de paternidad y para la identificación de individuos en la población nicaragüense residente en Costa Rica.

References

Acuña Ortega, V.H. 2001. Mito de la nación costarricense. La Nación, Suplemento Áncora, San José, Costa Rica, 8 abril: 1-2. (Also available online: http://www.nacion.co.cr/). [ Links ]

Alonso, A. & C. Albarrán. 2000. The Spanish and Portuguese ISFG Working Group: Ten years coordinating DNA typing in Spain, Portugal and Latin America. Profiles in DNA: 7-8. (Also available online: http://www.promega.com/profiles/401/401_07/). [ Links ]

Anonymous. 1995. Amplitype PM+ HLA-DQA1. Perkin Elmer, Roche Molecular System, New Jersey. p. 44. Anonymous. 1998a. Data supplied by Dept. Seville, National Institute of Toxicology (INT), Spain, p. 114. In O. García & I. Uriarte (eds.). Base de datos de ADN nuclear. Grupo Español y Portugués de la ISFH. Area Lab. Ertzaintza, Dept. Interior, Gobierno Vasco, Euscadi, España. [ Links ]Anonymous. 1998b. Data supplied by Dept. Madrid, National Institute of Toxicology (INT), Spain, p. 114. In O. García & I. Uriarte (eds.). Base de datos de ADN nuclear. Grupo Español y Portugués de la ISFH. Area Lab. Ertzaintza, Dept. Interior, Gobierno Vasco, Euscadi, España. [ Links ]

Anonymous 2001a. IX Censo nacional de población y V de vivienda del 2000: Resultados generales. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos, INEC, San José, Costa Rica. 80 p. [ Links ]

Budowle, B., J.A. Lindsey, J.A. Decou, B.W. Koons, A.M. Giusti & C.T. Comey. 1995. Validation and population studies of the loci LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8, and Gc (PM loci), and HLA-DQ-alpha using a multiplex amplification and typing procedure. J. Forensic Sci. 40: 45-54. [ Links ]

Carracedo, A., M.S. Rodríguez-Calvo, C. Pestoni, M.V. Lareu, S. Bellas, A. Salas & F. Barros. 1997. Forensic DNA analysis in Europe: Current situation and standardization efforts. Forensic Sci. Int. 86: 87-102. [ Links ]

Castillo, M.I., M. Paredes, C. Peñuela, I. Bustos, N. Jiménez & A. Galindo. 1996. Determination of the allele and genotype frequencies of loci HLA-DQA1, LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8 and GC in Bogota-Colombia. Advance. Forensic Haemogenet. 6: 503-505. [ Links ]Cerda-Flores, R.M., S.A. Barton, C.L. Hanis & R. Chakraborty. 1994. Genetic variation by birth cohorts in Mexican Americans of Starr County, Texas. Amer. J. Hum. Biol. 6: 669-674. [ Links ]

Dobles, A. 2001. El "otro" nica al imaginarnos. La Nación, Suplemento Áncora, San José, Costa Rica, 8 abril: 3. (Also available online: http://www.nacion.co.cr/). [ Links ]

Felsenstein, J. 1989. PHYLIP: Phylogeny inference package (version 3.2). Cladistics 5: 164-166. [ Links ]

Gómez, J. & A. Carracedo. 2000. The 1998-1999 collaborative exercises and proficiency testing program on DNA typing of the Spanish and Portuguese working group of the international society for forensic genetics (GEP-ISFG). Forensic Sci. Int. 114: 21-30. [ Links ]

Herrera, M., C. Asperilla, M.A. Aumente, L. Prieto, E. Arroyo & J.M. Ruiz de la Cuesta. 1996. Frequency data on the loci LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8 and GC in a population resident in Madrid (Spain). Advance. Forensic Haemogenet. 6: 547-548. [ Links ]

Jorquera, H. & B. Budowle. 1998. Chilean population data on ten PCR-based loci. J. Forensic Sci. 43: 171-173. [ Links ]

Long, F., R.C. Williams, J.E. McAuley, R. Medis, R. Partel, W.M. Tregellas, S.F. South, A.E. Rea, S.B. McCormick & U. Iwanec. 1991. Genetic variation in Arizona Mexican Americans: Estimation and interpretation of admixture proportions. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 84: 141-157. [ Links ]

Lorente, M., J.A. Lorente, M.R. Wilson, B. Budowle & E. Villanueva. 1997. Spanish population data on seven loci: D1S80, D17S5, HUMTH01, HUMVWA, ACTBP2, D21S11 and HLA-DQA1. Forensic Sci. Int. 86: 163-171. [ Links ]

Merriwether, D.A., S. Huston, S. Iyengar, R. Hamman, J.M. Norris, S.M. Shetterly, M.I. Kamboh & R.E. Ferrell. 1997. Mitochondrial versus nuclear admixture estimates demonstrate a past history of directional mating. Amer. J. Phys. Anthropol. 102: 153-159. [ Links ]

Morales-Cordero, A.I., B. Morera, G. Jiménez-Arce, G. Sánchez-Rivera, F. Calafell & R. Barrantes. 2001. Allele frequencies of markers LDLR, GYPA, D7S8, HBGG, Gc, HLA-DQA1, and D7S80 in the general and minority populations of Costa Rica. Forensic Sci. Int. 124: 1-4. [ Links ]

Morera, B. & R. Barrantes. 1995. Genes e historia: El mestizaje en Costa Rica. Rev. Hist. 32: 43-64. [ Links ]

Padula, R.A., D.A. Gangitano, G.J. Juvenal & B. Budowle. 1999. Allele frequency in the population of Buenos Aires (Argentina) using AmpliType PM + DQA1. J. Forensic Sci. 44: 1320. [ Links ]Palomino, H., R.M. Cerda-Flores, R. Blanco, H.M. Palomino, S.A. Barton, M. de Andrade & R. Chakraborty. 1997. Complex segregation analysis of facial clefting in Chile. J. Craniofac. Genet. Dev. Biol. 17: 57-64. [ Links ]

Reynolds, J., B.S. Weir & C.C. Cockerham. 1983. Estimation of the coancestry coefficient: Basis for a short-term genetic distance. Genetics 105: 767-779. [ Links ]

Saitou, N. & M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: Anew method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evolut. 4: 406-425. [ Links ]

Sandoval, C., A. de la Hoz & E. Yunis.1993. Estructura genética de la población colombiana. Rev. Fac. Med. Univ. Nac. Colomb. 41: 3-14. [ Links ]

Sandoval García, C. 1999. Notas sobre la formación histórica del "otro" nicaragüense en la nacionalidad costarricense. Rev. Hist. 40: 107-125. [ Links ]

Sans, M. 2000. Admixture studies in Latin America: From the 20 th to the 21 st century. Hum. Biol. 72: 155-177. [ Links ]

Singer, S.J. & R.L. Tanguay. 1989. Use of chelex to improve the PCR signal from a small number of cells, p. In Amplifications, a forum for PCR users, (September) Issue 3. [ Links ]

Schneider, S., J.M. Kueffer, D. Roessli & L. Excoffier. 1997. Arlequin vers. 1.1: A software for population genetic data analysis. Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva, Switzerland. [ Links ]

Schmidt, A. 1979. Los extranjeros en Costa Rica, p. 57-70. In Sétimo Seminario Nacional de Demografía. San José, Costa Rica. [ Links ]

Terreros-Ibanez, G., I. Bustos-Bustos & A.G. Ríos. 1999. Genetic characterization of the loci HLA DQA, LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8 and GC in a Bogota born population sample. Acta Biol. Colomb. 4(2): 80. [ Links ]

Woo, K.M. & B. Budowle. 1995. Korean population data on the PCR-based loci LDLR, GYPA, HBGG, D7S8, Gc, HLA-DQA1, and D1S80. J. Forensic Sci. 40: 645-648. [ Links ]

Internet references

Anonymous. 2000. Statistical and population genetics issues affecting the evaluation of the frequency of occurrence of DNA profiles calculated from pertinent population database(s). Forensic Sci. Comm. 2 (3): July. (Downloaded: February 23, 2001. http://www.fbi.gov/programs/lab/fsc/backissu/july2 000/dnastat.htm). [ Links ]Anonymous. 2001b. Database of nuclear DNA. The Spanish and Portuguese Working Group of the International Society for Forensic Genetics (GEP-ISFG). (Downloaded: September 4, 2001. http://www.ertzaintza.net/adn_nuclear). [ Links ]

Chen Mok, M., L. Rosero Bixby, G. Brenes Camacho & M. León Solís. 2000. Migrantes nicaragüenses en Costa Rica 2000: Volumen, características y salud reproductiva. Programa Centroamericano de Población, Escuela de Estadística and INISA, Universidad de Costa Rica. (Downloaded: October 30, 2000. http://populi.eest.ucr.ac.cr/). [ Links ]

Meléndez Obando, M. 1999. Centroamérica: Orígenes comunes. La Nación Digital, Columna Raíces, San José, Costa Rica, Edición 4. (Downloaded: September 2, 2001. http://www.nacion.co.cr/ln_ee/ ESPECIALES/raices/raices10.html). [ Links ]

Page, R.D.M. 1998. Tree View (Win 32) 1.5.2. (Downloaded: September 2, 2001. http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod.html). [ Links ]