Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Acta Médica Costarricense

versión On-line ISSN 0001-6002versión impresa ISSN 0001-6012

Acta méd. costarric vol.63 no.2 San José abr./jun. 2021

Original

Palliative care needs in Costa Rica by province

1 Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social. Hospital Nacional Geriátrico Raúl Blanco Cervantes, San José, Costa Rica

“Palliative care” refers to the approach aimed at people with advanced diseases and their families when the medical expectation is no longer a cure. It is an approach whose main objective is to improve the quality of life of the patient and his or her family by providing comprehensive care delivered by interdisciplinary work teams.1, 2

Each country has particularities in palliative care, so it has been documented as an essential task to calculate the palliative care needs for each region and different methods have been proposed to measure them, usually using causes of death as a starting point.1, 3-10 Costa Rica lacks the necessary information to determine palliative care needs that will allow prioritizing the distribution of resources, with distributive justice and optimizing institutional support to the maximum. Currently, resource planning is based on general population projections or local experience This document seeks to estimate the palliative care needs of the Costa Rican population and to analyze their frequency at the national level, according to diagnoses and province of domicile, to provide inputs for planning the distribution and allocation of resources for end-of-life care services.

Methodology

In 2018, the Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief described a new way to measure palliative care needs, starting with severe health-related suffering and defined as “suffering associated with the need for palliative care.” 9

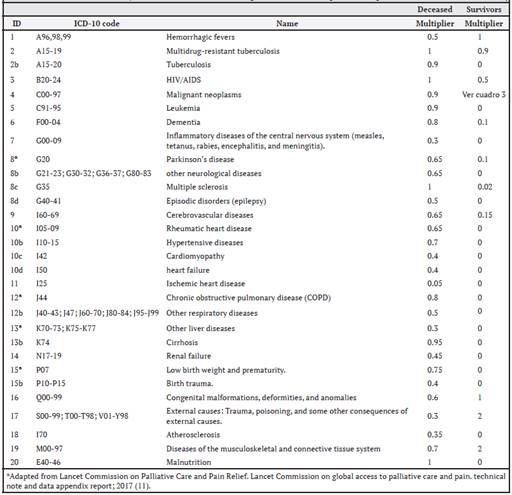

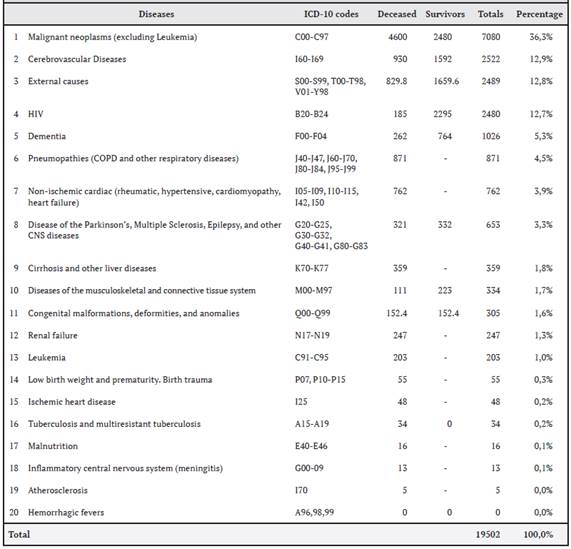

Initially, a group of experts identified the 20 diseases that generated the greatest need for palliative care in the world. For the classification of these diseases and subsequent calculations, the tenth International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes of these 20 diseases were used (Table 1).11

Table 1. Disease codes are chosen by the Lancet Commission according to ICD-10 and the respective multiplier for the deceased and survivors*

Estimates were worked on two different groups of this population, the deceased (patients who died in the year of study due to one of the 20 diseases) and the survivors (patients who suffered from the disease in the year studied).

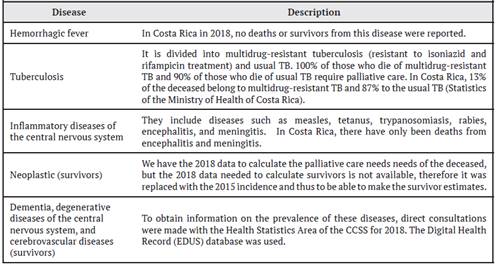

For the final calculation of palliative care needs for each group of diseases, the Lancet group, based on expert criteria, developed a multiplier for each disease to establish the proportion of deceased persons who were suffering and who would eventually require palliative care. This information is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Particular characteristics of some diseases for the calculation of palliative care needs

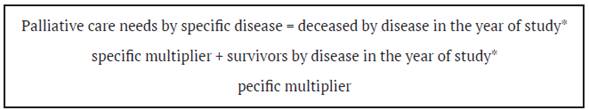

Palliative care needs for each specific disease are calculated from the sum of the product of the deceased for each specific disease in the study year by the disease-specific multiplier and the patient survivors for each disease with its respective multiplier in the study year; as shown in the formula below:

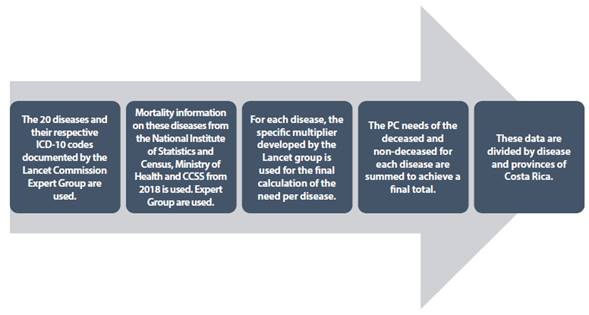

The total need for palliative care would be the sum of the palliative care needs for each specific disease. For the present study, the aforementioned methodology was used and which is detailed in another publication. 11 The methodology used in this study is summarized in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Methodology for the calculation of palliative care needs in the present study based on the Lancet Commission Method.

Calculation of palliative care needs of patients in Costa Rica:

In the case of the palliative care needs of the group of the deceased, the researchers of this work used the data available from the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INEC), on general deaths in Costa Rica, for the period 2018, as this was the latest period recorded at the time of the study. INEC classifies the causes of deaths using the ICD 10 Codes and allows their analysis by the province of residence. For some particular diseases, the information required for the calculation of need was obtained from data from the Ministry of Health, the Expediente Digital en Salud (EDUS), and the CCSS statistics office, as summarized in Table 2.

As in The Lancet Commission Report, the calculation of palliative care needs by survivors, i.e. those who did not die from one of the conditions in the study year, is also included using the multipliers summarized in the table below.

These individuals may have suffered and therefore need palliative care or pain control as they may have conditions that may have been cured but suffering persists, conditions in which patients survive for a year or more with a disability, or have pain for years.11

Results

a. National level palliative care needs.

Table 3 summarizes the general calculations obtained. Using the methodology described above, it was determined that 19502 people require palliative care in Costa Rica.

At the national level, it was documented that neoplastic diseases occupy first place in the prevalence of conditions requiring palliative care, followed by cerebrovascular diseases, external causes (which include trauma, poisoning, trauma from heat, cold, electricity, and traffic accidents, among others) and HIV-AIDS, and in a distant fifth place, dementia syndromes. When dividing terminal illnesses into oncological and non-oncological, the latter represents 62% of the palliative care needs in the country. This ratio is maintained throughout all provinces, except in Cartago, Limón, and Guanacaste, where the percentage of non-oncological disease is slightly higher.

Table 3. Palliative care needs by disease in 2018 in Costa Rica

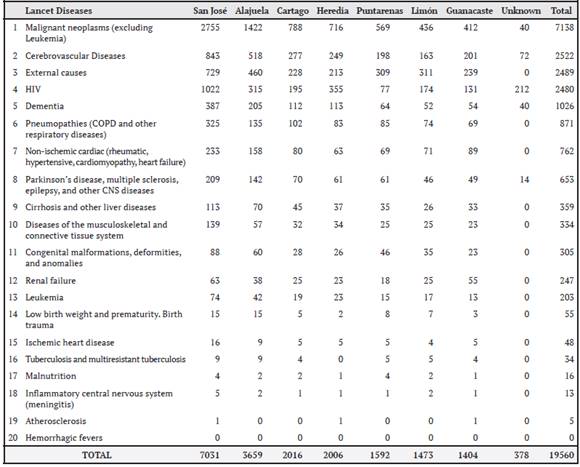

A comparison of palliative care needs by province (see Table 4) shows that most cases are located in the central provinces of the country, mainly San José and Alajuela. In third place is the province of Heredia. The coastal provinces, mainly Guanacaste, have fewer palliative care cases.

Table 4. Palliative care needs by disease in 2018 in Costa Rica, by province

When analyzing the 5 diagnoses that justify palliative care needs in the country (see Table 3), 4 diagnoses consistently appear among the causes of palliative care needs in all the provinces of the country. Neoplastic diseases are the first diagnosis that justifies these needs in all of them. The other 3 diseases are HIV-AIDS, cerebrovascular disease, and external causes. Dementias are in fifth place in the provinces of the central valley, pneumopathies in the provinces of Puntarenas and Limón, and heart disease in Guanacaste.

Discussion

Palliative care needs in the country are proportionally related to the population density of each province, with the provinces with the largest populations having the greatest need. Cancer is the most frequent disease in all provinces, a phenomenon that occurs worldwide, due to the increase in the incidence of this pathology. When classifying the diseases requiring palliative care into oncologic and non-oncologic, most of the palliative care needs in Costa Rica come from nononcologic diseases, and the ratio is maintained in most of the provinces, in percentages very similar to those compared worldwide. 1

Palliative care needs were calculated using two different types of populations, the deceased and the non-deceased (9). However, the deceased group is the largest contributor to the caseload in contrast to previous studies.1, 9, 10 This is probably due to the adequate national registry of the deceased in the country kept by INEC, which is not the case in other countries in the world with weaker health systems.9 In Costa Rica, it is evident that the relationship between non-oncologic and oncologic pathologies is similar to previous studies,9,10 except for the latest research conducted by the WHO.1 In this research, the global cases of oncologic disease are much lower, due to the high need for palliative care for non-oncologic causes in all regions, except for the European and American regions. The behavior of Costa Rica is very similar to that presented in the subgroup of the American region, as expected. 1

When analyzing the results specifically by diseases, the increase in the need for palliative care due to external causes is noteworthy, which is double that presented in previous publications,9 even when compared with the subregion of the Americas,1,13 where accidents of this type are higher than in other regions of the world.12 The behavior of this cause is comparable to that of the Eastern Mediterranean and Southeast Asian subregions. Costa Rican culture has aspects of gender and citizen compliance with the law that may explain this behavior. 13

This study documents that palliative care needs for the cerebrovascular disease are much higher than in the rest of the American region.1 An increasing trend in cerebrovascular disease mortality in Costa Rica in the last decade can be partially explained by the sustained increase in the burden of risk factors such as age, arterial hypertension, and high body mass indexes.14

Concerning HIV, the behavior is similar to that found in the Southeastern subregion and the Americas. In Costa Rica, despite the efforts made, there is evidence of an increasing trend of HIV for multiple sociocultural and health reasons, mainly in San José and Heredia.15

On the other hand, palliative care needs for tuberculosis are much lower than those presented worldwide, as well as for hepatopathies.9 With tuberculosis, the adequate control of the disease by the country’s health authorities explains the low number of cases related to this pathology.16

The needs for palliative care for dementia are particularly lower than those presented worldwide, but similar when compared to the rest of the American region1. This could be due to the underreporting of dementia as a cause of death.17, 18 It is striking that dementia is not identified as a cause of death in the poorest regions, such as the American and African regions. The data relating to pneumopathies are similar to worldwide publications. 1,9

In the coastal provinces, heart disease (Guanacaste) and pneumopathies (Limón and Puntarenas) are among the first five causes of death requiring palliative care. These causes are not among the first in the central provinces of the country, even though it is in these areas where most people die from pneumopathies.19

Finally, this research represents a first approach to the reality and national needs of palliative care. The methodology used can be improved since it is based mainly on the diagnosis of the disease, there being more complex and difficult to quantify factors that could increase the need for palliative care. 20 However, diagnosis continues to be one of the most frequently used reasons for referrals in these analyses. On the other hand, causes of death often do not adequately reflect the diagnosis of care. For example, dementia,17 Parkinson’s21, and nephropathies22 are frequently underdiagnosed as causes of death, as usually these patients ultimately die from infectious diseases such as bronchopneumonias, urinary tract infections, etc.

Despite this, this first approach that seeks to know the palliative care needs at the national level by province is an invaluable support for the planning of services and the allocation of resources in a fairer, more equitable, and supportive manner.

Abbreviations: CCSS: Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social ICD 10: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10. INEC: Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos / National Institute of Statistics and Census. WHO: World Health Organization HIV: Human Immunodeficiency Virus-AIDS Sources of support. None Conflicts of interest. No conflicts of interest are considered to exist with the publication of the article. jepicado@ccss.sa.cr

Referencias

1. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Atlas of Palliative Care 2nd Edition. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance; 2020. Available http:// www.thewhpca.org/resources/global-atlas-on- end-of-life-care (modified 30/4/2021). [ Links ]

2. Radbruch, Lukas et alt. Redefining Palliative Care-A New Consensus-Based Definition. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2020; 60. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.04.027. [ Links ]

3. Murtagh FE, Bausewein C, Verne J, Groeneveld EI, Kaloki YE, Higginson IJ. How many people need palliative care? A study developing and comparing methods for population-based estimates. Palliat Med. 2014 Jan; 28 (1): 49-58. doi: 10.1177/0269216313489367. Epub 2013 May 21. PMID: 23695827. [ Links ]

4. Grbich C, Maddocks I, Parker D, Brown M, Willis E, Piller N and Hofmeyer A. Identification of patients with noncancer diseases for palliative care services. Palliative and Supportive Care. 2005; 3: 5-14. [ Links ]

5. Mitchell H, Noble S, Finlay I and Nelson A. Defining the palliative care patient: its challenges and implications for service delivery. British Medical Journal Support Palliative Care. 2012. [ Links ]

6. Rosenwax LK, McNamara B, Blackmore AM, et al. Estimating the size of a potential palliative care population. Palliat Med. 2005; 19 (7): 556-562; [ Links ]

7. Gómez-Batiste X, Martinez-Munoz M, Blay C, et al. Identifying needs and improving palliative care of chronically ill patients: a community- oriented, population-based, public-health approach. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012; 6 (3): 371-378; [ Links ]

8. World Health Organization (WHO). Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. London: Worldwide Palliative Care Alliance ; 2014 Available at: http://www.thewpca.org/ resources/global-atlas-of-palliative-care/. [ Links ]

9. Knaul FM, et alt. Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief Study Group. Alleviating the access abyss in palliative care and pain relief-an imperative of universal health coverage: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet. Apr 7 ;391(10128):1391-1454. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32513-8. Epub 2017 Oct 12. Erratum in: Lancet. 2018 Mar 9: PMID: 29032993. [ Links ]

10. Sleeman, Katherine, De Brito, Maja & Etkind, Simon & Nkhoma, Kennedy & Guo, Ping & Higginson, Irene & Gomes, Barbara & Harding, Richard. The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. The Lancet Global Health. 2019; 7. 10.1016/S2214-109X (19) 30172-X; [ Links ]

11. Lancet Commission on Palliative Care and Pain Relief. Lancet Commission on global access to palliative care and pain. Technical note and data appendix report; . 2017, 12 Octubre. Recuperado de: https://www. mia.as.miami.edu/_assets/pdf/Data%20 appendix%20LCGAPCPC%20Oct122017_ ONLINE-DRAFT%2012OCT17.pdf. [ Links ]

12. de la Peña Enrique, Millares Lourdes, Díaz Alejandro, Taddia Claudia Bustamante. Experiencia de éxito: resumen ejecutivo (Internet). Washington DC, EE.UU : Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo.; 2016. Disponible en: https://publications.iadb. org/publications/spanish/document/ Experiencias-de-%C3%A9xito-en-seguridad- vial-en-Am%C3%A9rica-Latina-y-el-Caribe- Resumen-ejecutivo.pdf. [ Links ]

13. Bohián P. Estadísticas de siniestros viales con víctimas en Costa Rica para el período 2012- 2016 (Internet). Dialnet.unirioja.es. 2020 (cited 31 July 2020). Available from: https://dialnet. unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/7594405.pdf [ Links ]

14. Páramo D. Actualización en la prevalencia y carga de la enfermedad cerebrovascular en Costa Rica en el período comprendido entre 2009-2019. (Internet). Revistamedicacr.com. 2020 (cited 31 January 2021). Available from: http://www.revistamedicacr.com/index.php/ rmcr/article/view/313. [ Links ]

15. Rodríguez Montero P, Rodríguez Montero P. Aspectos epidemiológicos del virus de inmunodeficiencia humana en costa rica (Internet). Scielo.sa.cr. 2018 (cited 31 January 2021). Available from: https:// www.scielo.sa.cr/scielo.php?script=sci_ arttext&pid=S1409-14292018000200118. [ Links ]

16. Mata-Azofeifa, Z , Baraquiso Pazos, M. Análisis de la mortalidad por tuberculosis, en Costa Rica (Internet). Scielo.sa.cr. 2020 (cited 28 Nov. 2020). Available from: https:// www.scielo.sa.cr/pdf/amc/v62n3/0001-6002- amc-62-03-126.pdf. [ Links ]

17. Martyn CN and Pippard EC. Usefulness of mortality data in determining the geography and time trends of dementia. J Epidemiol Community Health8. 1988; 42(2): 134-137. [ Links ]

18. Fornaguera J, Segura N, Montero-Herrera B. Enfermedad de Alzheimer en Costa Rica. Una realidad poco investigada. (Internet). 2018 (cited 5 January 2021). Available from: https:// www.researchgate.net/publication/334469816_ Enfermedad_de_Alzheimer_en_Costa_Rica_Una_ realidad_poco_investigada/citation/download. [ Links ]

19. Chinchilla, Jairo, Evans-Meza, Ronald, Bonilla Roger y Romero Águeda). Evolución de la carga por enfermedades pulmonares crónicas en Costa Rica, 1990-2014. REV HISP CIENC SALUD. 2018; 4 (2): 65-77. [ Links ]

20. Field D and Addington-Hall J.Extending specialist palliative care to all? Soc Sci 1999, 1271-1280. [ Links ]

21. Phillips NJ, Reay J and Martyn CN. Validity of mortality data for Parkinson’s disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999; 53 (9): 587-558. [ Links ]

22. Li SQ, Cass A and Cunningham J. Cause of death in patients with end-stage renal disease: assessing concordance of death certificates with registry reports. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2003; 27(4): 419-424. [ Links ]

Received: February 09, 2021; Accepted: August 18, 2021

texto en

texto en