Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Acta Médica Costarricense

On-line version ISSN 0001-6002Print version ISSN 0001-6012

Acta méd. costarric vol.58 n.2 San José Apr./Jun. 2016 Epub June 01, 2016

Articles

Analysis of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia in Patients from Mexico hospital

1Unidad Cuidados Intensivos,Hospital Escalante Pradilla

2Servicio de Infectología, Hospital México, Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social. Sistema de Estudios de Posgrado, Universidad de Costa Rica crisao7282@gmail.com

In recent years there has been an increase in gram - negative pathogens that produce β - lactamases, it has contributed as an important factor of β - lactam antibiotic resistance. There is a group of β - lactamases of extended spectrum (ESBL) that have a resistance mechanism capable of hydrolyzing and causing resistance to various antibiotics, such as new β - lactamics, including third - generation cephalosporins of broad spectrum (ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, ceftazidime) and monobactams (aztreonam.)1 usually, these strains also express co-resistance to cephamycines, fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines and trimethoprim /sulfamethoxazole, which difficult further treatment.2 This type of pathogens represent the cause of poor therapeutic response to cephalosporins used in an appropriate way, and entail serious consequences of morbidity and mortality.3 In the last two decades, gram - negative bacilli of the family that express ESBLs are mainly: Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis. 4

ESBL Klebsiella pneumoniae (KPBLEA +) represents a serious emerging problem. The worldwide prevalence varies in different geographical regions, most of them are nosocomial acquired, with rates between 7.5 and 44%.5 KPBLEA + rate was 44% in Latin America, 22.4% in Asia / West Pacific, 13.3% in Europe and 7.5% in the United States.6.7

A data source called TEST, from 22 European countries, shows that between 2004-2007, 515 isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae, documented that ESBL expression was 15.5%, being highest in Greece and lowest in Denmark. 8

Most infections caused by Klebsiella are acquired in hospitals and occur in patients with debilitating conditions.9,10 They are usually respiratory, urinary tract, intra - abdominal infections and bacteremia.11.12 Other infections described are: wound infections, invasive infections or intravascular devices related infections, biliary tract infections, peritonitis, meningitis, myonecrosis and crepitant cellulitis.

Bacteremia by these strains are associated with higher treatment failure and increased mortality. Some studies report mortality of 14% for bacteremia by Klebsiella pneumoniae not producing ESBL (KPBLEA-) and 68 % for bacteremia by KPBLEA +.16 The common risk factors are: prolonged hospitalization and intensive care units the risk factors are: severe illness, catheters, invasive and surgical procedures , renal replacement therapy, ventilatory support and the use of β- lactamcis and fluoroquinolones.17

In the study, the main objective was to determine the association between the infection site of origin or KPBLEA + KPBLEA- and the development of bacteremia.

In addition, the most common sites of infection, the risk factors for acquiring infection, ESBL expression, development of bacteremia and mortality associated with bacteremia were also determined.

Methods

A retrospective observational study was performed, which studied patients admitted to Hospital Mexico between January 2008 and December 2011, with Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. To be included in the study, patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: adults between 18 to 85 years of age, patients with surgical, medical, gineco-obstetrical pathology, emergency, critical care, without exception of gender, ethnicity, country of origin or nationality. Records with incomplete information, pediatric and geriatricpopulation, patients over 85 years of age were excluded. The study protocol complied with the requirements of the IRB at Hospital Mexico.

All clinical characteristics, comorbidities, invasions, antibiotics received, growth parameters, relevant laboratory work out, clinical markers of severity, and mortality at 30 days were tabulated. All analyzes were performed based on the comparison of the established groups.

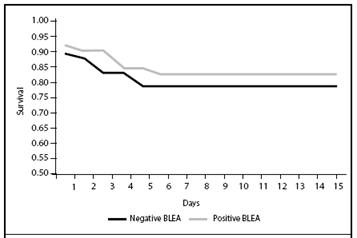

After data collection we proceeded to describe the variables studied using descriptive statistics, measures of central tendency and dispersion for quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequency distributions for qualitative variables. Intervals were calculated with 95% confidence for comparison between groups. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed through a non - conditional model to establish the possible factors that predisposed to present a KPBLEA +, including statistical significance variables. For the assessment of survival at 30 days, a multivariate model using Cox regression was developed, the primary endpoint was the presence of ESBL and other variables were included according to their level of significance. Kaplan Meier graphs were used to compare survival between KPBLEA- and KPBLEA +, and depending on the types of appropriate, inappropriate and readjusted treatment. Microsoft Excell updated program and SPSS version 18 software were used.

Results

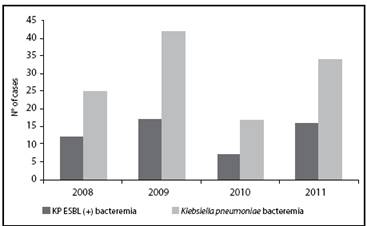

In the period between 2008 and 2011, there were 191 patients who had a total of 286 bacteremias by Klebsiella pneumoniae. Among these, 118 cases of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia, 56% KPBLEA- and 44% KPBLEA +, for an approximate ratio of one to one. From the bacteremias that were collected, a not significant sample corresponded to bacteremia in different hospitalizations of the same patient or in the same hospitalization but in a recurrent manner. The vast majority of the sample corresponded to bacteremia for the first time (Figure 1).

The cumulative incidence for the period studied was on average 1.0 per 1000 admissions, very similar for both groups. There was an increase in the cumulative incidence in 2009, after a decline in 2010, and subsequently a further increase in 2011 for a statistically significant change (Figure 2).

With respect to the variables studied, most patients were admitted to the Internal Medicine Department, on average aged close to 50 years, all febrile, with leukocytosis and left deviation, with increased acute phase reactants like CRP and procalcitonin, and rapid growth rates. The site of origin of infection, in most patients, was not possible to identify. The average stay of patients from admission until the of blood culture test, it was was higher for KPBLEA +.

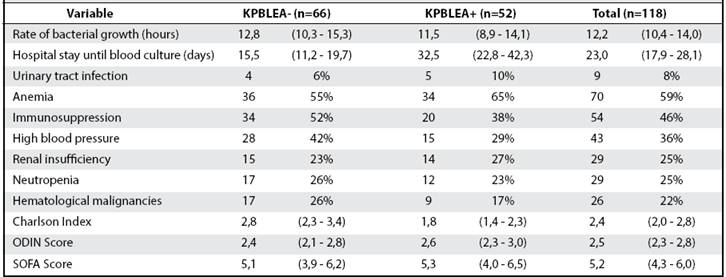

Among the most frequent comorbidities were anemia, immunosuppression, hypertension, renal insufficiency, neutropenia and hematological malignancies. Regarding the Charlson comorbidity index, it was observed that patients generally had a lower comorbidity and patients with KPBLEA + showed lower values in this index, a difference that was statistically significant (p = 0.008). As for the scores of SOFA and ODIN, there was virtually no difference between patients for each type of Klebsiella (Table 1).

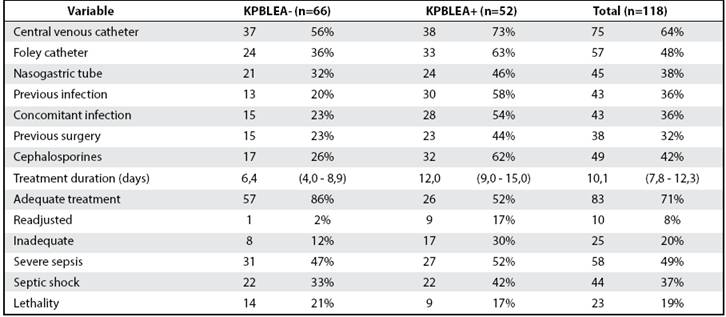

The most frequent risk factor in patients were: the presence of central venous catheter, foley catheterization and nasogastric tube, previous infection in the past 30 days, concomitant infection and previous surgery: factors that were practically the same when patients were analyzed according to the type of Klebsiella. The most common surgeries were abdominal followed orthopedic.

It was not possible to establish a significant difference between the average numbers of days of different devices analyzed and the type of Klebsiella (Table 2).

Table 1 Variables analyzed in patients with positive blood cultures for Klebsiella pneumoniae, according to the presence of ESBL , Mexico Hospital from 2008 to 2011

Table 2 Variables analyzed in patients with positive blood cultures for Klebsiella pneumoniae, according to the presence of

One of the factors studied in these patients was prior treatment received. In order of frequency, the three most common types of antibiotics were cephalosporins, aminoglycosides and penicillina. For cephalosporins, KPBLEA + patients received 5 to 6 days more of treatment, with a statistically significant difference (95% CI 1.9 to 9.3%, p: 0.004) (Table 2). For other antibiotics, treatment times were very similar and the difference was not significant.

When describing the type of treatment received by patients, this was classified as appropriate, if the antibiotic indicated had activity against the germ; readjusted, if initially the treatment was inadequate and then the correct one was indicated, and inappropriate if the antibiotic had no activity against the germ. It was found that patients with KPBLEA -bacteremia were treated more frequently with a useful treatment (86%, 95% CI: 76.5 -93.1%) than those with a KPBLEA + bacteremia (52%, 95% CI: 36, 6 -63.4%) (Table 2).

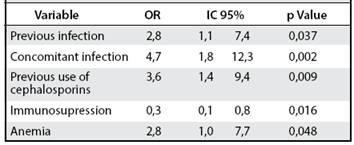

Of the predisposing factors found to present a KPBLEA +, it was found that this risk was increased for the following reasons: having had a previous infection by Klebsiella, presenting concomitant infection with Klebsiella bacteremia, have used cephalosporins, having suffered anemia, and have placed Foley catheter (95% CI 1.1 to 12.3%). By contrast, the presence of immunosuppression decreased this probability in 70% chance and favored the presence of KPBLEA- infection (Table 3).

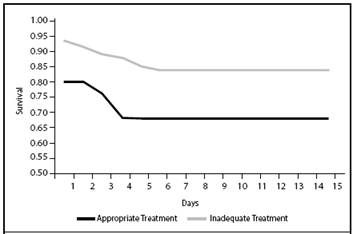

As for the evolution of patients, subjects with KPBLEA + developed more frequently severe sepsis and septic shock, but patients with KPBLEA- showed higher lethality. This is confirmed by the estimation of survival

at 30 days by Kaplan - Meier, which shows that patients with KPBLEA + had a better survival over the period studied (Figure 3). Despite this, it was not possible to established that these differences were statistically significant, and the presence of ESBL did not increase the probability of dying.

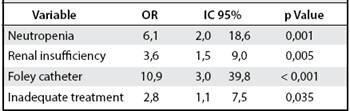

However, other factors studied, neutropenia, renal insufficiency, the presence of Foley catheter and an indication of inadequate treatment did increased lethality (95% CI 1.1 to 39.8%) (Table 4). Also, when the survival was evaluated, depending on the type of treatment, it was found that with proper treatment the patients had a higher survival unlike patients with inadequate treatment (Figure 4).

Figure 3 Kaplan-Meier estimation for 30-day survival of patients with positive blood cultures by Klebsiella pneumoniae, according to the presence of BLEA, Hospital México, 2008 - 2011

Discussion

Our study demonstrates the behavior of an emerging germ as Klebsiella pneumoniae in the Hospital Mexico.

We seek to establish an epidemiological precedent to be a comparative basis for future studies in our hospital.

The change in the observed incidence could mean that something happened in 2010 that made the incidence decrease but was not maintained through time. This must be analyzed with caution, because patients who did had bacteremia in 2010 accounted for 35% of the total population, and we could only obtain information from 25%. This decrease in incidence can only reflect the lack of data collected. However, a cumulative incidence was reported within the range of documented worldwide data.

Table 3 Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with the presence of KPBLEA + in patients with positive blood cultures for Klebsiella pneumoniae, Mexico Hospital 2008-2011

Referring to the variables in leukogram and inflammatory markers, these reflected that in the presence of bacteremia, the patient manifested a systemic inflamatory response, as expected. If it is observed with the average growth rate of 12.2 h, it can be inferred that the patient had a high load of inoculum when he had bacteremia, which is reflected in the fact that most patients developed sepsis.

Regarding the most frequent comorbidities, these indicate that most patients who had bacteremia KPBLEA- and KPBLEA +, had a background of immunopatergia that could have predisposed them.

When analyzing the information, only anemia increased the likelihood of KPBLEA + bacteremia. The anemia factor is a common condition in hospitalized patients, usually of a multifactorial etiology. In this case, anemia can reflect a patient with a longer hospital stay, more comorbidities, and increased risk of getting infected with a multidrug resistant germ. It was also shown that neutropenia and renal insufficiency increased the likelihood of death. The latter two factors associated with immunopatergia and undoubtedly will increase mortality in bacteremia, both KPBLEA- as KPBLEA +. In addition, sepsis is the leading cause of acute renal insufficiency in critically ill patients. Up to 51% of patients in septic shock develop renal insufficiency. This involves loss of metabolic homeostasis and electrolytes, and is related to the increased mortality.

Of the invasions, only the presence of foley catheter increased the likelihood of death. If this finding is taken parallel to the fact that urinary tract infection is the most common infection associated with bacteremia, and now the presence of foley catheter represents an invasion that may increase mortality, one might assume that many of these primary bacteremias may have had a hidden source of infection at urinary level. This can orient that many of these patients may have been colonized enough time to then express their resistance mechanisms: type BLEA, ending in more severe infections and bacteremia.

This can also be proved when we note that the history of previous infection increased the likelihood of KBLEA + bacteremia. Among other risk factors, there is no doubt that the previous surgery is a bloody noxa that predisposes a patient to infection by germs such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, and represents an invasion, handling and potential contamination. It is noteworthy that, remarkably, other variables mentioned in reviews, such as mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, and parenteral nutrition, not represented common risk factors for the development of bacteremia.

Table 4 Multivariate analysis of risk factors associated with mortality at 30 days in patients with positive blood cultures for Klebsiella pneumoniae, Hospital Mexico , from 2008 to 2011

Referring to the average stay of patients, the data from literature is confirmed, because the greater the hospital stay, the greater the risk of acquiring KPBLEA + bacteremia. With respect to prior exposure to antibiotics, as described, it was greater exposure to β - lactam in KPBLEA +. Cephalosporins were the main risk factor for ESBL expression. In definitive, exposure to cephalosporins could predispose the transfer via plasmids, of ESBL resistance mechanisms in bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, ESBL subsequent expression and association to more severe infections.

Also KPBLEA + subjects more frequently developed severe sepsis and septic shock, but KPBLEA- patients had a higher lethality, with no statistical significance. It is interesting to analyze these data because patients that were KPBLEA + were those who had lower Charlson comorbidity scores, and those who had higher severity SOFA and Odin scores. This could mean that even though KPBLEA + patients had worse clinical evolution to septic shock, they had higher survival. Probably, the higher number of comorbidities in patients was the final determinant in lethality, not strictly, the presence of ESBL. Another interesting aspect is that this could be an example of that resistance is not the same as virulence.

It may be that the expression of type ESBL resistance mechanisms, represent a higher metabolic cost to the bacteria, which sacrificed its virulence. So, KPBLEAmay end up being more virulent and lead to increased mortality.

Finally, referring to antibiotic treatment, proper treatment was a determinant for a higher survival. Based on these findings, the policies of antibiotic coverage should be improved for patient risk factors, thinking in the possibility of infection with a multidrug resistant germ.

Regarding the limitations of the study, retrospective information only collected only 41% of bacteremias occurred during the period of investigation. In addition, the study is limited to a single center.

Work done in Infectious Diseases Department, Hospital Mexico, Costa Rican Social Security, San José, Costa Rica.

Authors’ Affiliations: Intensive Care Unit, Escalante Pradilla Hospital; Department of Infectious Diseases, Hospital Mexico, Costa Rican Department of Social Security.

System of Graduate Studies, University of Costa Rica. crisao7282@gmail.com

Referencias

1. Pitout J., Laupland K. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae: An Emerging Public-Health Concern. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8: 159-66. [ Links ]

2. Falagas M. E., Karageorgopoulos D. E . Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase- Producing Organisms. J Hosp Infect 2009; 73: 345-354. [ Links ]

3. Skippen I., Shemko M., Turton J., Kaufmann M.E., Palmer C., Shetty N. Epidemiology of Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase- Producing Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella Spp.: A Nested Case-Control Study From a Tertiary Hospital in London. J Hosp Infect 2006; 64: 115-123. [ Links ]

4. Rahal J., Urban C., Horn D., Freeman K., Segal-Maurer, Maurer J., et al. Class Restriction of Cephalosphorin Use to Control Total Cephalosphorin Resistance in Nosocomial Klebsiella. JAMA 1998; 280: 1233-1237. [ Links ]

5. Lin, J-N., Chen Y-H, Chan L-L, Lai C-H, Lin H-L, Lin H-H. Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes of Patients With Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Bacteremias in the Emergency Department. Intern Emerg Med 2011 October. [ Links ]

6. Deen, J., Seidlein L., Andersen F., Elle N., White N. J., Lubell Y. Community- Acquired Bacterial Bloodstream Infections in Developing Countries in South and Southeast Asia: a Systematic Review. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12: 480-487. [ Links ]

7. Bradford, P. A. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in the 21st Century: Characterization, Epidemiology, and Detection of this Important Resistance Threat. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001; 14: 933-951. [ Links ]

8. Chen Y-H, Lu P-L, Huang C-H, Liao C-H, Lu C-T, Chuang Y-C, et al. Trends in the Susceptibility of Clinically Important Resistant Bacteria to Tigecycline: Results from the Tigecycline In Vitro Surveillance in Taiwan Study, 2006 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 56: 1452-1457. [ Links ]

9. Chopra I., Shofield C., Everett M., Oneill A., Miller K., Wilcox M., et al. Treatment of Health-Care-Associated Infections Caused by Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Consensus Statement. Lancet Infect Dis 2008; 8: 133-39. [ Links ]

10. Leavitt, A., Chmelnitsky I., Colodner R., Ofek I., Carmeli Y, Navon-Venezia S. Ertapenem Resistance Among Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiella Pneumoniae Isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2009; 47: 969-974. [ Links ]

11. Update: Detection of a Verona Integron-encoded Metallo-Beta-Lactamase in Klebsiella Pneumoniae-United States, 2010. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention MMWR. 2010; 59:1212. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/ mmwr. [ Links ]

12. Carnaglia, G., Giamarellou H., Rossolini G. M. Metalo-β-Lactamases: A Last Frontier for β-Lactams?. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11: 381-93. [ Links ]

13. Digiola, R. A., Kane J. G., Parker R. H. Crepitant celullitis and myonecrosis by Klebsiella. JAMA 1977; 237: 2097-2098. [ Links ]

14. Ma L-C, Fang C-T, Lee C-Z, Shun C-T, Wang J-T. Genomic Heterogeneity in Klebsiella Pneumoniae Strains is Associated With Primary Piogenic Liver Abscess and Metastasic Infection. J Infect Dis 2005; 192: 117-28. [ Links ]

15. Nordmann, P., Cuzon G., Naas T. The Real Threat of Klebsiela Pneumoniae Carbapenemasa Producing Bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis 2009; 9: 228-36. [ Links ]

16. Cordery, R. J., Roberts C. H., Cooper S. J., Bellinghan G., Shetty N. Evaluation of Risk Factors for the Acquisition of Bloodstream Infections With Extended- Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia Coli and Klebsiella Species in the Intensive Care Unit; Antibiotic Management and Clinical Outcome. J Hosp Infect 2008; 68:108-115. [ Links ]

17. Steward C. D., Rasheed J. K., Hubert S. K., Biddle J. W., Raney P. M., G. J. Anderson. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Detection for Clinical Laboratory Standards Laboratories Using the National Committee Klebsiella pneumoniae from 19 Characterization. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39: 2864-2872. [ Links ]

Received: April 28, 2015; Accepted: February 04, 2016

text in

text in