Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Acta Médica Costarricense

versión On-line ISSN 0001-6002versión impresa ISSN 0001-6012

Acta méd. costarric vol.54 no.1 San José ene./mar. 2012

Review

Tobacco Economics

Economía del Tabaco

M. Cecilia Monge Bonilla, MPH

Servicio de Medicina Interna 4, San Juan de Dios Hospital

Abbreviations: CCSS, Caja Costarricense de Seguro Social; WHO, World Health Organization

Correspondence:

Abstract

Sound medical evidence testifies that tobacco use and inhaling "secondhand" smoke from cigarettes raises the risk of morbidity, mortality and disability. Tobacco use is a major worldwide public health issue. Many countries still hesitate to act decisively to reduce tobacco, because they are concerned that the harm caused by tobacco may be offset by the economic benefits that the country derives from tobacco. The production, export and import of tobacco and tobacco products make up an insignificant part of Costa Rica's economy. The concern that tobacco controls will cause permanent job losses in an economy is not the case in most countries. Falling demand for tobacco does not mean a fall in a country's total employment level. Money that smokers once spent on cigarettes would instead be spent on other goods and services, generating other jobs. Evidence from countries of all income levels shows that price increases on cigarettes are highly effective in reducing demand. Higher taxes induce some smokers to quit and prevent other individuals from starting, especially young citizens. Another concern is that higher taxes will lead to massive increases in smuggling but the evidence shows that, even where smuggling occurs at high rates, tax increases bring greater revenues and reduce consumption. Smuggling is directly associated with the corruption level of each country. Experience in high and middle-income countries shows that strict tobacco control with smoke free policies do not have a negative economic impact in the hospitality industry both in net economic gains and employment levels.

Keywords: tobacco control, smoke free laws, economic evaluation, Costa Rica, World Health Organization, Framework Convention on Tobacco Control

There are approximately 1.100 million adult smokers worldwide, 80% of them live with low and medium incomes. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), each year tobacco kills one million people in America and 5 million worldwide. Smoking is the leading preventable cause of death. If current smoking trends continue, by 2030, 1 out of every 6 adults will die because of tobacco. 500 million people alive today will eventually die as a consequence of smoking, 50% of them will do so in the middle ages, losing 20 to 25 productive life years.1

In Costa Rica, 15% of the population smokes. Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social (CCSS, Costa Rica´s Social Security fund) invests 58 000 million colones each year, caring for diseases associated with tobacco consumption, representing almost 6% of CCSS´s health insurance costs. Besides, because of tobacco-associated disabilities, 55,000 working days are lost every year, and ten people die every day from smoking-associated diseases. CCSS provides 858,000 annual smoking-associated medical consultations.2

Tobacco consumption and its secondhand smoke exposure are associated with 90% of lung cancers and 30% of cancer deaths. It also has influence in the development of 80% of cases of chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and 30% of deaths from coronary artery disease.2

Science has shown that tobacco consumption and exposure to its smoke are causes of death, disease and disability, and despite the imminent health risk that tobacco represents worldwide, it causes an indisputable harm, proven in thousands of scientific articles.

Clearly, tobacco consumption and exposure to its smoke cause death, disease and disability, and represent an imminent public health risk worldwide. But governments are hesitant to adopt legal and political measures required to reduce tobacco consumption, fearing the negative economic consequences that such regulations might imply.

Tobacco control economics is a complex issue, given the economic interests encircled. Roughly, it can be divided into five basic economic arguments, commonly used by the tobacco industry against strict tobacco control. These include the economic impact of strict tobacco control laws and policies, in workplaces, cultivation and cigarette production, the consequences of tax increases in tax revenues; the effect of tax increases in smuggling; the socio-economic impact as a result of taxes, and economic implications of 100% non-smoking environments.

Worldwide, approximately 5.5 trillion cigarettes are smoked annually, generating half a trillion dollars in sales. The regional market is dominated by two companies: Philip Morris International (34% of the regional market), whose best-selling cigarette brands are Marlboro and Derby, and British American Tobacco (55% of the regional market), with brands such as Belmont, Delta, Kent, Kool, Rex and Viceroy.3

WHO, determined to give prioritize their right to protect health, developed the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), in response to the global tobacco epidemic. The Convention is based on scientific evidence, and supports the preamble to the WHO's human right constitution to the highest health standards; it is stated that enjoying the highest attainable health status is a fundamental right of every human being, without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition. 168 States are party to the Convention, so that it represents 75% of the world´s population.5 The main goal is to protect present and future generations against health, social, environmental and economic consequences from tobacco consumption and smoke exposure, by providing a framework for tobacco control measures to be implemented to national, regional and international levels in order to reduce continually and substantially the prevalence of tobacco consumption and smoke exposure.6 The Convention was adopted unanimously at the WHO´s World Assembly in 2003, and is the first international public health agreement. It was ratified in Costa Rica on July 7th, 2008.6,7

Regarding the implementation of legal and political tobacco control measures, there are two fundamental questions: What economic consequences are implied after strict tobacco control policies and laws? And, Is there enough economic evidence to implement strict tobacco control policies and laws? There is now enough data and experience to answer these questions and thus to take informed decisions, seeking a better life for citizens.

Some of the most relevant arguments used by the tobacco industry opposed to tobacco control are: decreased employment for tobacco cultivation and cigarette production, decreased tax revenues when increasing taxes that raise cigarette costs, increased smuggling as a result of high taxes, economic losses for bars, restaurants and hotels, and job losses as a result of laws for 100% non-smoking environments.

1. Cultivation and production employments

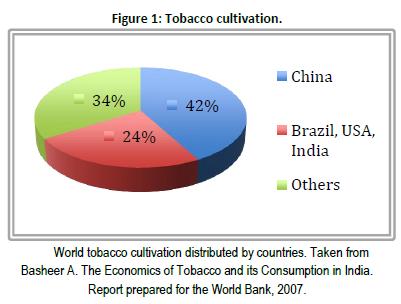

An important reason why governments do not act aggressively concerning tobacco control is due to fear of a significant job loss in cultivation and production; but this is not what is shown by the evidences. Nearly 100 countries cultivate tobacco, 80 of them are developing countries and 4 are responsible for two thirds of the world´s crop. In 2009, China grew 42% of the world´s tobacco, while India, Brazil and the United States produced 24%. Brazil is the second largest worldwide tobacco grower. Colombia and Venezuela are also important tobacco growers. In the remaining 34%, Turkey, Zimbabwe and Argentina play a significant role.8

Malawi and Zimbabwe are the only two countries whose economies depend on tobacco. Although this is the dominant product for many farmers in India, in other tobacco growing countries, it is just a component of a diversified agriculture strategy. In places with relatively large crops, such as Brazil and China, only 1.5% of the arable land has tobacco (Figure 1).

Even in optimal agro-ecological regions, tobacco is difficult to grow and requires exhaust manpower, so that it is an expensive product. Gross profits from tobacco farming are high, but net earnings are not greater than other crops, when taking into account the high costs of seeding, manpower and soil fertility depletion. Tobacco is attractive to farmers because its industry gives them loans and credits, and prices tend to be stable, because of subsidies in some developed countries, especially in the United States, trying to protect small farmers.9

In Costa Rica, according to the Ministry of Agriculture, tobacco cultivation is minimal. 10 Philip Morris Inc. has one manufacturing plant, and British American Tobacco products are imported mainly from Honduras, where they have their own production plant. There are small cigar producers nationwide, however, their goal market are Costa Rica´s visiting tourists, or people who buy them in countries where these are exported. Tobacco industry is a very limited source of employments, as cigarette-making is a highly mechanized process. For most countries, including Costa Rica, cigarette production jobs represent less than 1% of those in the manufacturing area.

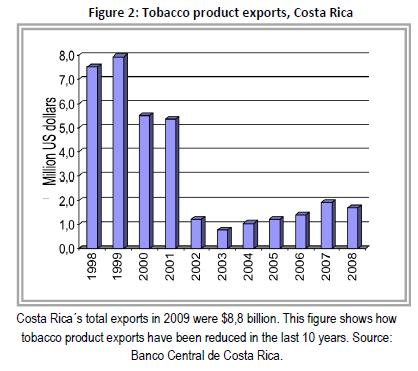

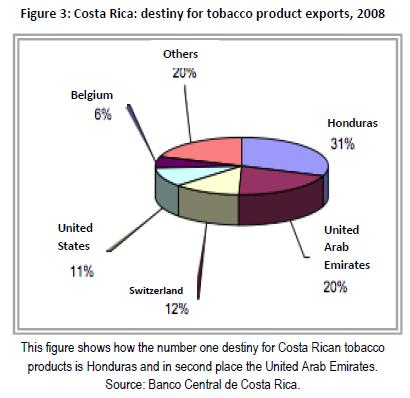

In terms of tobacco products´ foreign trade, in Costa Rica, since 2009, exports were less than $ 2 million, with a total of $ 8.8 billion in that same period (Figure 2). 50% of Costa Rican exports are distributed in two countries: Honduras and United Arab Emirates, who buy Costa Rican raw tobacco. Switzerland, the United States and Belgium are, mainly, cigarette buyers (Figure 3).

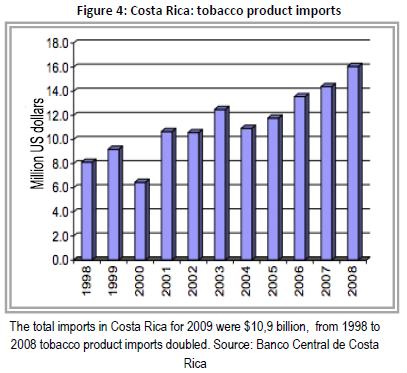

Almost two thirds of tobacco product imports made by Costa Rica in 2008 were cigars and cigarettes, while raw tobacco accounted for 28% (it is imported as a raw material for the local industry). In the cigars and cigarettes category, cigarettes accounted for virtually all imports, which reflect, to some extent, consumers´ preferences, as in Costa Rica cigarettes are preferred rather than cigars.

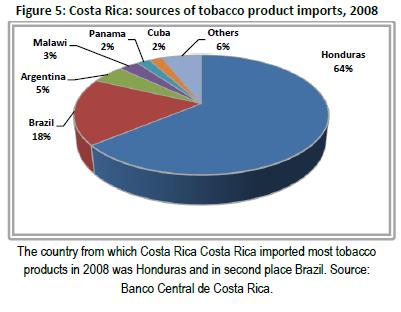

Tobacco product imports enter Costa Rica mainly from Honduras, and benefit from customs tax exemption, due to agreements from the Central American Common Market.5 In 2008, 64% of products which entered Costa Rica were imported from that country. Imports from Brazil, Argentina or Malawi are raw tobacco, the raw material for the local industry (Figure 4).

Tobacco production is just a tiny part of the Costa Rican economy; contrary to the industry´s threat, strict tobacco control would not produce net job losses. A decrease in consumption, which would lead to an employment decrease in the tobacco industry, does not mean a decrease in the country´s total employment. Economic theory says that it would generate a change in consumption patterns: money spent purchasing cigarettes would be spent on other products. Most goods have more labor requirements than cigarettes, which are produced in a highly mechanized process, so that would new jobs would be required.13

There are economic projections that show this fact. A study from the United Kingdom found that there would be a 100 000 jobs increase if all current smokers spend their money to buy cigarettes in other products or luxuries.14 Another study in the United States calculates a theoretical 20 000 jobs increase between 2003-2008, if all tobacco consumption was removed and the money used to purchase other products. This type of calculation is not limited to developed countries: in Bangladesh the same study projected that there would be an 18% increase in jobs nationwide, if tobacco consumption was removed.15

Tobacco farming-dependent countries would constitute an exception, such as Malawi and Zimbabwe, but these would have a market large enough to ensure their jobs for many years, even if there was a decrease in global demand.15

2. Taxes and tax revenues

It has been shown that increasing taxes is the most effective measure to reduce tobacco consumption; causing smoking reduction and cessation, affecting especially beginners, the young and the low socioeconomic class.16 A study published by the World Bank indicates that a 10% price increase on cigarettes worldwide would save 1 million lives in Latin America and 4 million smokers would stop smoking.17

Tobacco is a substantial revenue source for governments, through taxation, which is particularly significant in developing countries, since these taxes are easy to collect. In countries such as China, tobacco taxes account for up to 11% of government revenues.18

Experience from other places has shown that politicians are often opposed to tobacco tax increases, arguing that the resulting decrease in demand and sales will cost significant revenues to the government. However, the contrary has been proven: even though increasing prices due to tax raises would decrease cigarette consumption and sales, consumption would fall by a smaller proportion compared to the tax increase, resulting in a net increase in tax revenues. Therefore, in terms of revenues, the tax increase exceeds the losses from reduced consumption.

3. Smuggling

Increasing tobacco taxes, increases government´s revenues, and stimulates smoking cessation, an especially effective strategy towards young people. Many governments fear an increase in smuggling, which would significantly decrease tax revenues from tobacco, however, evidence demonstrates otherwise. An increase in taxes does not result in a significant smuggling increase. The boost of smuggling by the tax increase is very little, so that even with a slight increase in smuggling, total tobacco consumption in the population is reduced.21

Preliminary results of a study examining cigarette exporting from the United States and the United Kingdom to 109 countries concluded that a 10% increase in the price of tobacco reduces consumption by 3.5%, with little smuggling increase of about 1%, resulting in a 10% increase in tax revenues. The current study used global tobacco price elasticity of -0.5.22

4. Socio-economic aspects

Tobacco taxes are regressive and have a higher effect on the low socioeconomic class. There is a high smoking prevalence in men with a low socioeconomic status, with its related illness and premature death risks.25 Smoking and deaths because of tobacco play a key role in poverty. A study by Efroymson and colleagues included 20 thousand people from 23 countries, and concluded that, if poor people did not smoke, potentially 10.5 million would not be malnourished in Bangladesh. Besides, it showed that a family member´s disease or premature death is the most common cause of a worsening poverty status.26, 27

5. 100% non-smoking environments

Tobacco smoke has harmful and even fatal health consequences on children, such as induction and exacerbation of asthma, bronchitis, pneumonia, middle ear infection, chronic respiratory problems, low birth weight and sudden infant death syndrome, among others.

An article published in 2004, studies passive smoking in Latin America, specifically in Costa Rica, Chile, Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay and Peru. Vapor phase nicotine is used, a tracer type specific marker for monitoring and quantifying secondhand tobacco smoke exposure.

Secondhand cigarette smoke concentrations were analyzed in public spaces, finding that 51.5% of students between seventh and ninth grade had been in the presence of a smoker for over 20 minutes in the last 7 days. Samples were taken at the San Juan de Dios and Mexico Hospitals, and found air levels of nicotine vapor, of 5ug/m3, although smoking is prohibited in hospitals. In restaurant non-smoking areas, there were vapor nicotine air levels of 4.5ug/m3. Only at Juan Santamaría Airport, levels were as expected: none.28

Over 20 serious studies assess the economic effects of strict tobacco regulation by 100% non-smoking environments. They use indicators such as total reported sales for tax purposes and employment statistics in restaurants, hotels and bars. All, both in developed and developing countries, have concluded that there is no economic effect in bars, restaurants and hotels, when introducing 100% smoke-free environments.29, 30

Strict tobacco control through policies and laws is economically beneficial to Costa Rica, and it would represent an important gain in tax revenues. There is evidence that there are no economic sale losses or employment decreases in hotels, bars and restaurants, when introducing the law for 100% non-smoking environments.

It is fundamental for Costa Rican public health, to have a tobacco control law which has severe efficient and impressive measures to decrease tobacco consumption, with significant taxes and exposure restrictions, by implementing 100% non-smoking environments, among other measures.

It is unethical and unacceptable to assign an economic value to human life or suffering.

Conflict of interest: the author of this article has no conflicts.

Translated by: Javier Estrada ZeledónReferences

1. Abedian,Iraj,R.vanderMerwe,N.Wilkins,andP.Jha.eds.1998. TheEconomics of Tobacco Control: Towards an Optimal Policy Mix. University of Cape Town, South Africa. [ Links ]

2. Campos A. Estimados de fumado en Costa Rica, 2010. En: http://www.ccss.sa.cr [ Links ]

3. Crosbie E, SebriEM, GlantzSA.Strong Advocacy led to Successful Implementation of Smokefree Mexico City.Tob Control 2011; 20:64-72 [ Links ]

4. Shafey O, Eriksen MP, Ross H, Mackay J.The tobacco Atlas, 3rd edition. Atlanta, Georgia: American Cancer Society; 2009. [ Links ]

5. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Article 4.7. Geneva: WHO; 2003. En: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/index. html. [ Links ]

6. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control: Article 5.3. Geneva: WHO; 2003. En: http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/index. html. [ Links ]

7. Euromonitor International (Base de datos en Internet). Cigarettes: LatinAmerica. Euromonitor International. c 2009 (citado septiembre, 2009). [ Links ]

8. Basheer RA. TheEconomics of Tabaco and its Consumption in India.Report prepared fortheWorld Bank, 2007. [ Links ]

9. Bialous, S. A. and S. Shatenstein (2002). Profits Over People: Tobacco Industry Activities to Market Cigarettes and Undermine Public Health in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC, PAHO. En:http://repositories.cdlib.org/tc/reports/LA2/ [ Links ]

10. Bianco E, Champagne B.The tobacco epidemic in Latin America and the Caribbean: A snapshot. Prevention and Control 2005;1(4): 311-17 [ Links ]

11. British American Tobacco Company inaugurates Regional Centre in Costa Rica. InsideCosta Rica; 2007 [citado septiembre,2009]. En: http://insidecostarica.com/business/2007/november/07-11-21.htm. [ Links ]

12. Philip Morris International (PMI).2008 Annual Report. New York: PMI; 2009. En:http://investors.philipmorrisinternational.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=146476&p=irol-reportsannual. [ Links ]

13. Hu TW, Mao Z. Economics of Tabaco Discussion Paper, Health, Nutrition and Population, World Bank, November, 2002. [ Links ]

14. Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. DHHS Publication No.(CDC)88-8406.U.K. Department of Health, 2008. En: http://www.official-documents.co.uk/. [ Links ]

15. Ranson, Kent, P. Jha, F. Chaloupka, and A Yurekli. Effectiveness and Cost-effectiveness of Price Increases and Other Tobacco Control Policy Interventions.Background paper,2004. [ Links ]

16. Jaffee, S., World Bank,2002; Jha P and Chaloupka, F. Tabaco Control in Developing Countries, OUP for the World Bank and WHO, 2000. [ Links ]

17. Peto, Richard, A. D. Lopez, and L. Boqi. Global Tobacco Mortality: Monitor- ing the Growing Epidemic. In Lu R., J. Mackay, S. Niu, and R. Peto, eds. [ Links ],

18. The Growing Epidemic Singapore: Springer-Verlag (en impresión). [ Links ]

19. USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture). EconomicResearchServiceDatabase, 2008. En: http://www. econ.ag.gov/prodsrvs/dataprod.htm [ Links ]

20. Tobacco Manufacturers' Association.Royal College of Physicians, 2009. En: http://www.the-tma.org.uk/tma-publications-research/facts-figures/tax-revenue-from-tobacco/ [ Links ]

21. Gamboa F. Impacto en la recaudación tributaria del impuesto específico planteado en el Proyecto de "Ley sobre el control del tabaco y sus efectos nocivos para la salud".Organización Panamericana de la Salud, 2010. En: http://www.paho.org/ Spanish/AD/SDE/RA/Tab_Econ_ [ Links ]

22. Joossens L. A Public Health Priority: Curbing the Epidemic, World Bank, 1999. En: http://www.usaid.gov/policy/ads/200/tobacco.pdf [ Links ]

23. Watkins BG. The Tobacco Program: An Econometric Analysis of Its Benefits to Farmers. American Economist 1990;34(1):45–53. [ Links ]

24. Sweanor, DT, Martial LR. The Smuggling of Tobacco Products: [ Links ]

25. Lessons from Canada. Ottawa (Canada): Non-Smokers' Rights Associa-tion/Smoking and Health Action Foundation.Canadian Cancer Scy 2004. [ Links ]

26. Joossens, L, Raw, M. Smuggling and Cross-Border Shopping of Tobacco in Europe. Br Med Jour 2005; 310(6991):1393–97 [ Links ]

27. Townsend J.Cigarette Tax, Economic Welfare, and Social Class Patterns of Smoking.Applied Economics 2007;19:355-65 [ Links ]

28. Efroymson D, Phuong DT, Huong TT, Tuan T, Trang NQ, Thanh VPN, et al. Decision Mapping for Tobacco Control in Vietnam: Report to the International Tobacco Initiative. PATH Canada. Project 94-0200-01/02214. [ Links ]

29. Ensor, T. Regulating Tobacco Consumption in Developing Countries. Health Policy and Planning 2002, 7:375–81 [ Links ]

30. Navas-Aciena A, Peruga A, Zavaleta A,Pitarque R, Acuña M, Jiménez-Reyes K, et al.Secondhand Tobacco Smoke in Public Places in Latin America, 2002-2003. JAMAA 2004;291(22): 2741-45 [ Links ]

31. ShahrirS, WipfliH, Avila-TangE, BreysseP, SametJ, Navas-AcienA. Tobacco sales and promotion in bars, cafes and nightclubs from large cities around the world. Tob Control 2011;20:285-90 [ Links ]

32. ChampagneBM, SebriéEM, Schargrodsky H, PramparoP, BoissonnetC, WilsonE.Tobacco smoking in seven Latin American cities: the CARMELA study. Tob Control 2010;19:457-62 [ Links ]

Received: September

5th, 2011 Accepted: September 22nd, 2011

texto en

texto en